How do we tell the deeper story that matters in a way that engages readers? How can we tackle the inner critic, self-censorship and fear of judgment? And does social media actually sell books? Nikesh Shukla talks about why Your Story Matters and gives his writing tips.

In the intro, Amazon opens up Ads to traditionally published authors; How to Make a Living with your Writing; Ultimate Guide to Multiple Streams of Income [ALLi]; Cemeteries and Graveyards [Books and Travel]; Death’s Garden Revisited Kickstarter. Plus, From $0 to $1K in book sales, free book marketing webinar with Nick Stephenson.

Today’s show is sponsored by IngramSpark, who I use to print and distribute my print-on-demand books to 39,000 retailers including independent bookstores, schools and universities, libraries and more. It’s your content – do more with it through IngramSpark.com.

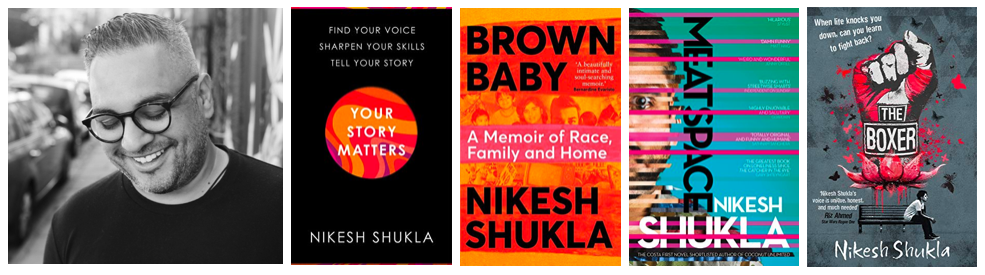

Nikesh Shukla is a best-selling novelist as well as a screenwriter, editor, podcaster and essayist. He has been named one of Time magazine’s cultural leaders, Foreign Policy magazine’s 100 global thinkers, and he’s a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. His latest nonfiction book is Your Story Matters: Find Your Voice, Sharpen Your Skills, Tell Your Story.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Learning a hard publishing lesson early on

- Finding our author voice

- How to deal with fear of judgment and self-censorship

- Planning a novel and shaping a story

- The two different types of writer procrastination

- Searching for the emotional truth of a story

- Does social media sell books?

You can find Nikesh Shukla at Nikesh-Shukla.com, Nikesh.substack.com and on Twitter @nikeshshukla

Transcript of Interview with Nikesh Shukla

Joanna: Nikesh Shukla is a best-selling novelist as well as a screenwriter, editor, podcaster and essayist. He has been named one of Time magazine’s cultural leaders, Foreign Policy magazine’s 100 global thinkers, and he’s a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. His latest nonfiction book is Your Story Matters: Find Your Voice, Sharpen Your Skills, Tell Your Story. Welcome Nikesh.

Nikesh: Hello.

Joanna: Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing.

Nikesh: I was quite a shy and awkward teenager, and I didn’t really like going out and doing all the sort of miscreant deeds that teenagers do. I just sat in my room and listened to a lot of rap, I read a lot of comics, and I would transcribe all of the rap lyrics and I would read the comics again and again and again.

After a while, I started writing my own rap lyrics and writing out my own arcs for Spider-Man and for Batman.

I guess some sort of fan fictiony type route is what brought me into writing. And then from that I graduated to what most teenagers do, which is write appalling poetry.

Joanna: Woohoo!

Nikesh: I think that’s probably where it all started for me is just being a shy teenager who had a lot to say about the world and the world was against me, but I could write down how I felt about the world.

Joanna: Obviously, you’re not a teenager anymore. So how did it go from terrible teenage poetry into Fellow of the Royal Society. Obviously, we’re both British, and I don’t know if Americans will realize this, this is a really big deal. How did you cross that gap?

Nikesh: Who knows? A series of unfortunate events, probably. I don’t know.

Here’s a thing that happened to me when I was a teenager, sort of my origin story.

I write about this in Your Story Matters.

But at some point, during my teenage years, I saw an advert for an international poetry competition. I think I was 15 or 16. And you have to submit a poem, and you could win a lot of money and go into an anthology. And I thought…I’m a sick poet.

So I sent off a poem that was your very standard teenage fare. Teenager goes for a walk, spots nature and nature reminds him that we’re all going to die someday. Really bad stuff. It was really bad.

And I sent that poem, it was called Train of Thought, or Trail of Thought. Get it? Because he was on a walk, a trail and he was having thoughts and the thoughts were wandering.

At some point, I got a letter back from the International Poetry Foundation, or whoever it was saying, ‘You haven’t won the International Poetry competition, but we love your poem, and we’re going to include it in our anthology, Awaken To A Dream.’ And I was like, ‘Oh, my God, I’m going to be published. This is amazing. Yes, this is happening. I’m on my journey now!’

Then it said, if you wish to be included in the anthology, then you have to buy a copy of the anthology which costs 50 pounds, but we will give you a discount of five pounds, so you just have to pay 45 pounds, and then you can be in the anthology, and we’ll send you a copy.’

I didn’t realize what the listeners are probably realizing right now, I was a teenager and I was desperate to be published. I was a prolific bad poet after all, until I begged my mom for the money. I saved up I pulled together savings, I sold some comics and I scrimped and saved and I managed to scrape together 45 pounds, got my mum to write a check, gave her the money.

I think she knew what I think we’re all expecting to happen. I sent it off and then about six months later, I got a big package through the post and it was Awaken To A Dream.

Now, let me just describe Awaken To A Dream to you. It is A4 size. It is over 500 pages long. The paper is very thin, you know the type of paper you might lie in a cake tray with. And there are like between five and seven poems on each page.

Joanna: They made lot of money out of that!

Nikesh: They made a lot of money out that. We all paid 45 quid for that. I did the maths actually, I’ve spoken about this before. I did the maths. I imagine, because it was cheaply printed, and you were paying for package and posting, they would have cleared at least like 250,000 pounds from that. But that’s a very rough maths of how many people, how many poems were in there.

I was devastated because I’d really saved up as much as I could to get this poem in there.

The realization I had after that was that my words mattered.

And if they mattered, then I needed to make sure that they always were published in a way that highlighted how much they mattered.

So that was my origin story.

I kept writing. I was working on a book, when I was at university called Darkie. It was my attempt to tell my uncle’s story because my uncle had did some amazing activism in the late 60s when he came to the UK. I wanted to write his story, but it was just a story. It wasn’t characters, it was just me recording the things that I knew about my uncle, and not really knowing how to write a novel at 19.

But anyway, I went to a concert by the band Asian Dub Foundation, who were my band at the time, I was obsessed with them. They were just the most amazing band in the whole world. They were performing at the University of London union, and I went to see them.

Afterwards I saw their lead singer, a guy called Deeder Zaman, just hanging out. And I went to talk to him, and he was just the most lovely guy. He was really interested in me, really wanted to inspire young people. Told me to send him what I had of the book, which I did later on that evening, when I got home.

He gave me his email address. I send it to him and he was like, ‘This is great. Do you want to meet up for a cup of tea?’

I was like, ‘Oh, my God, I’m meeting Deeder Zaman from Asian Dub Foundation for a cup of tea.’ So I went to Green Street, which was near where he lived at the time. We sat, we drank tea, and we ate chaat. And we talked about writing and rap.

He asked me to read him some of my poems. And so I did. And he was like, these sound like raps. And I was like, ‘Do they?’ and he’s like, ‘Have you ever rapped before?’ I was like, no.

So he said, ‘Okay, come with me.’ He took me that day, took me back to his house. And he put some beats on and just taught me how to rap over an afternoon.

It was just the most inspiring moment of my life. It was the moment I stepped out of my shell. After that, I spent my 20s trying to be a rapper. I wasn’t very good. But I was inspired by him and by the space he gave me.

I was also writing short stories. And because I was really inspired by politics, I was using short stories to talk about unsung heroes.

I wrote this short story about this young boy called Zahid Mubarak, very big story about miscarriages of justice in the political system, in the prison system in the UK, and I wrote a short story about him. And I sent it off to an anthology.

Because at this point, it was the mid-aught-teens and I was doing a lot of spoken word stuff alongside the rap and alongside writing short stories, and surrounded by all these amazing poets like Musa Okwonga, and Selena Godan.

There was this guy called Nii Ayikwei Parkes who was running all these amazing nights. And he was also working on anthologies. One of them was called Tell Tales and volume one had just come out and it had like short stories by amazing writers. He was working on that with Courttia Newland, who was a hero of mine. I loved his novel, The Scholar.

They were then taking submissions for volume two, and I sent this short story about Zahid Mubarak in. They published it. And so actually, the first time I was ever properly published, was in a book edited by Rajiv Balasubramaniam and Courttia Newland, that Nii Parkes had put together.

The moment I realized that I was a writer, not a rapper, a novelist and a fiction writer, not a musician in any way, was the moment I got that package through the post.

Again it came to my parents house where I was living at the time. And this time, it was book sized, and it had a barcode, which I was like, ‘Oh my god,’ automatically this is legit, people can pay $9.99 in a shop and get this. And I looked at the contents list.

I’d been paid for it as well. I’ve been paid the most money that I’d ever been paid for a single job in my entire life by that point. And I was paid to be in an anthology with Kamala Shamsi and Leonie Ross and Romesh Gunesekera and Gemma Weeks ago, and Courttia Newland, my hero.

That was the point in which everything changed. I was like, I need to do this now, this is where my heart is at, this is what I’m good at. So that’s how I became a writer.

Joanna: I think what’s great about what you’ve just talked about, there, is one, how long things take. But two, you started by saying you are shy and awkward. And many of us here are introverts.

The people who did stay at home reading comics and books. That’s what we did, and still do, in fact. But then you stepped out and you met people, and you met some of your heroes, and you put your work out into the world, whether it was meeting that rapper for tea, and then it taking the opportunities as they come.

Even though that first rip-off, vanity press thing, that actually helped you, it helped push you into valuing your work, which is something that many people struggle with. I love that it took that long, and you did all of that.

Let’s come to the book, because there’s three parts, find your voice, sharpen your skills, tell your story. So let’s start with find your voice. Because again, this is the kind of a long term thing, and many writers struggle with voice.

How do you define author voice? Is it something we can easily find? Or do we just discover it over time?

Nikesh: This is a difficult thing. This is actually the thing that I don’t think can really be taught in creative writing classes. I think creative writing classes can show you the way to develop your voice, but they can’t teach you voice.

It’s so wrapped up in who you are as a person, as a writer, as with the interest you have, with the kind of the delivery in the execution that you want to attempt. With the lens that you want to cast upon the world and the tone that you want to give to it.

It’s so unique to you. I’m sure there are listeners amongst us. I’ll just give you a very live example of this. I think I know what my voice is. But then I read last year or the year before whenever it came out, or the last few years, obviously feel like one long year to me. But whenever I read Luster by Raven Leilani I was like, oh my god, this is amazing. I need to write like Raven Leilani. Why don’t I sound more like Raven Leilani?

I tried it. I tried to write like her, but I can’t write like her because only she can write like her. And also, I write like myself, and me writing my version of how Raven Leilani writes is just disingenuous. It’s not who I am, and it doesn’t do what she does any justice either.

I think voice is the uniqueness of you. Basically, it’s the thing that makes your voice you. It’s the thing that makes your story only the story that you could tell. We could all write a story about love, but only I can tell this story in this way, at this point in time.

Only you can tell that story that you want to tell at that moment in that way.

Voice is so wrapped up in the way we tell stories and the execution of the way we tell stories.

Actually, the only real way to learn that about yourself is to write and write…and write things that you’re comfortable writing and write things that you’re not comfortable writing and ways that you feel comfortable writing and write in ways that you don’t actually feel are your voice and just see what fits and just keep doing it and keep doing it and keep doing it.

And then it clicks.

My first novel is actually the third manuscript length thing that I wrote. As soon as I wrote it, I knew it was the one, because it hit the tone that I’d wanted to have all along.

Before I started that novel I had, I’d been given a book by Niven Govinden, a very dear friend of mine, and one of my mentors, he gave me Sag Harbor by Colson Whitehead. Amazing, amazing book. It’s one of the funniest books. And I am a comedy writer at heart.

I’m a big studier of comedy. That book gave me permission to write comedy. I read it and it was so funny and so warm and so textured and just so rooted in who the characters were. It made me realize that the thing that I wanted to do was write comedy.

That novel just came out of me in a way that felt true to my voice because it unlocked the missing piece of my voice, as it were.

I do think there’s a time element and there’s a doing it a lot element and there’s also a trusting yourself element as well. Because the other thing I think about creative writing classes and books about writing, I know I’ve just written one, is that they tell you so much about structure and they may do it in a very matter of fact way or an accessible way, like I’ve done, or they may even do it in a more esoteric way, or a sort of slightly more highbrow way.

The effect that they can sometimes have on writers is make them trust their instinct less and actually, our instinct is ultimately all we have. I always think that your instinct is the thing that’s telling you what your voice is. So learn to trust your instinct.

Joanna: I feel like I found my voice in like book five. But then I didn’t write as much poetry as you. I was thinking one of the issues I always had with those early books was a fear of judgment. And therefore, I self-censored.

I had an instinct, but then I said, ‘Oh, I can’t lean into that instinct. Because what if people think X about me?’

What would you say to people who might be struggling with fear of judgment or self-censorship?

Nikesh: If I knew the answer to this. I still struggle with that. I still struggle with that imposter syndrome. I still struggle with the inner critic.

There’s actually a section in Your Story Matters where I talk about how to work with alongside your inner critic, because I think, often our inner critic is a self-defense mechanism that we can listen to what it’s trying to say, rather than trying to fight against it.

The main thing to say is, rejection is part of the writing process. Because it’s always a process of whittling it down to the one agent that can get it to the right editor who can get it to the right reader. And the thing is, once a book comes out, it doesn’t belong to you anymore.

It belongs to readers, and you will find that readers will project all manner of things onto your work that you may not even have considered. For example, I once got a one star…never read Goodread’s reviews, by the way.

Joanna: No, don’t go anywhere near it.

Nikesh: I once read a Goodreads review of my third novel where I got one star because I didn’t teach the reader enough about the British Empire. But it’s a multigenerational family drama. It’s not about the British Empire. Maybe go read a book by a historian. Mate, there are many out there.

So knowing that readers don’t read things objectively, we all project ourselves on to everything we read. So knowing all these things, I think it helps me to realize that actually, the only thing that matters really, for me, is making sure that the thing that I’m writing is the best thing that I can make it and it matches what my intentions in writing are.

Because there are so many other parts of the process that it doesn’t belong to me, after a certain point. As long as I get it to a position where it doesn’t belong to me anymore and I’m happy to say goodbye to it, then that, to me feels like the best way to think about it.

I also try and visualize the one reader who needs to read this book rather than think about the many readers who could read this book. I think about the one reader who needs it the most. And focus on them.

Joanna: That’s a good tip. I like that. And then you can also pretend they’re really friendly and nice and will write you a good review.

Nikesh: Yes. I spend so long telling other writers don’t read reviews, good or bad. Don’t go on Amazon, don’t check your sales ranking. Don’t ask your publisher for sales updates.

Don’t like scour the various listicles and go, ‘Why am I not on this listicle?’ Because there’s so much of it that you can’t control. But the other thing is, I probably do all that as well.

You can’t help yourself because there is a part of you that has just put a piece of your soul out into the world and you do want that external validation. I think for me, it’s important to recognize what external validation is helpful what external validation is unhelpful.

At various parts of my career, I found myself…what’s a nice way to put this…being the hate object of a lot of people because of my political views.

Once you’ve been through that kind of dragging on the internet, you realize that a lot of this stuff doesn’t matter. All that matters is that moment when it’s just you and the page, the silence of the room that you’re writing in. And that moment where you read back on the thing that you’ve just read, and you think, I’ve just articulated something that communes with the cosmos in some way.

Joanna: That’s great.

Moving on to the other parts of the book, you talk about sharpening your skills. Let’s talk about how you plan a novel because obviously, some authors plot, other people discovery write. And this is something that obviously is different between everyone.

How do you plan a novel? And how does that shape your story?

Nikesh: Look, I’ve written this book. And that doesn’t mean I take my own advice. I think each novel is very different, because I think different book ideas come to you in different ways.

There have been times where I’ve planned, I’ve had a really great idea. I planned it and planned it and planned it, and then the point in which I sit down to write it, it just doesn’t match the plan anymore.

And there have been times where I’ve just gone by the seat of my pants for that first draft. And then I’ve got to the end and when I come to the idea of like, ‘Oh my god, this is just too gargantuan a task, I don’t know if I love this enough to put all that time in.’

I would say that for every novel that gets published, there is a full-length manuscript that didn’t make it, because that’s just how I write.

Someone once said that a first draft is like shoveling sand into a sandbox that you will eventually make sculptures from and I really like that. But just to add to that, when you’re in the shower, or you’re doing the washing up, and this amazing idea comes to you, this amazing idea, your brain has entered buffering mode, because you’re just doing something that doesn’t really require much thought and your mind wanders.

By the time you get to your desk from the shower, or from the washing up to record the amazing thought, you record it, you then look back at it, and it never matches that amazing thought that was in your head.

That to me is the early draft. It’s that sort of slippage that occurs between thought and execution. And so much of the editing and the rewriting is about getting it closer to the head thought.

I think giving yourself permission to spend a lot of time in the edit, and also giving yourself permission to plan but also adjust as you go because you want to give yourself the freedom to find new things as you write. Because as you get to know the characters more, you discover different things about them. And if you don’t give yourself that space, then you can end up paralyzing yourself.

So much of writing a novel is knowing what your intention is for the novel, what your big question at the heart of the novel is.

Also planning and knowing the general direction, but also allowing yourself to find new things as you go. And also giving yourself time to edit.

In the mess of all of these things, and novel emerges. I also really think that it’s important when you’re writing a novel. I think it’s time. I see so many writers every single week, it seems, spout the same thing about write 1,000 words a day. I just think it’s nonsense.

To go, ‘You must write 1000 words a day, if you’re to be a writer.’ I would much rather spend an hour a day on a book. Because time for me is more important than volume.

I’d much rather have the time to write two great sentences, than write 1,000 words a day. On some days, I can do that in 45 minutes and other days, it’s a real hard struggle, and I’m just padding out and then I’ve got that meeting coming up.

I might have to just fill out the word count with nonsense that I know I’m going to have to delete in six months time when I come to the edit. What’s the point of that? So just spending time is the most helpful thing. I think.

Joanna: I agree on that 1000 words a day. When I’m trying to get a first draft done, I will try and get those first draft words out. But then, like you say, if you move into an edit process, then you’re not putting out 1000 words a day, but you tend to finish the draft and then go back and edit or cycle through.

Everyone’s different. And every book is different too.

Nikesh: 100%. This isn’t school. So we’re not like fighting against the very concept of mainstream institutional education. You’ve chosen to write a book. So you have to really think about the best way in which you work.

You also have to understand that there’s useful procrastinating and there’s useless procrastinating. Useful procrastinating is getting into Google holes, and doing research and reading stuff and all the rest of it. As long as you’re doing that alongside your manuscript, that is great.

Then there’s useless procrastinating, which is like going, ‘Oh, I’ve got a great idea for a short story, I’m going to work on something else.’ But you know the best way that you work, so really think about that.

I write best in the morning. So I try and do all of that stuff in the morning. I know that I work in 45 minute bursts. So I do that.

Also, every novel is different. The novel I’m working on at the moment, which is not at the point where I really feel like I can talk about it in any useful way. But the novel I’m writing at the moment, I’m writing it slightly differently to how I’ve written previous things, because it’s so much more of an experiential novel, and a character study, rather than like a plot driven thing.

I need to write it slower and spend more, more…fewer words…how do I explain?Yeah, see, I can’t talk about this. I was going to say, try and say something like, semi sensible about the writing of it, but actually I’m just spending a lot more time being forensic about it.

It’s a novel about captured moments rather than a novel where this happens, it forces this person to make a choice, that choice has consequences, then that they have to make another choice, and so on, and so forth. It’s a series of fragments, and it needs to be treated as such.

Joanna: We’ll keep an eye out for that in a few years’ time.

But the other part of the book, tell your story. I think this is really interesting, because you mentioned that you have a political stance, you have some issues that you have tackled in public, and I feel like there’s this fine line between wanting to communicate important truths about the world and society. Then there is delivering a story that readers love to be engaged with.

There’s that balance between preaching and storytelling. How do we tell this underlying important story while still telling a good story that readers love?

Nikesh: Good question. I think the way to do this is to remember that telling a story isn’t about giving us the black and white of it. No one wants to read an essay, or a short story, or a piece of fiction that is binary in any way that goes, ‘This is right and this is wrong. This is good and this is bad.’

We’re much more interested in the greys, we’re much more interested in the complexity of life and the complexity of people.

The way I talk about it in my class, is I’d say, those of us who’ve seen Avengers Endgame, if you imagine that film is Thanos’ film, then you realize that you’ve got a really complicated protagonist at the heart of it, because Thanos is set up as the villain. But he is a complicated, compromised villain.

He believes what he’s doing is right. He has a point. And it’s important for us as readers or viewers to always think that our antagonists have their own moral code. They are doing something that they think is right, and that they’re maybe going about it in a way that’s slightly different to how we might go about it.

He’s going to lose things along the way. And he’s going to make compromises along the way, but they will push him towards his singular vision.

That’s what makes him an interesting villain, because at some point, you should be able to go…’He kind of has a point.‘ Which then makes the film and the whole concept of good versus bad, good versus evil or right versus wrong very interesting, because maybe if Thanos had had a better teacher, or better mentor or better parent than maybe he wouldn’t have gone about deleting half the universe.

If you apply that to writing about issues or writing about the way society is, think about what the emotional truth of what you’re trying to write is, think about the ways you can complicate those emotional truths, and just think about not having people come at it from fixed positions.

If they are coming at it from fixed positions, mess with those fixed positions as much as you can.

What you what is for a character to go on a journey, and come out the other side. This is how Kurt Vonnegut described it in; there’s a really good lecture he does called The Shapes of Stories, which you can find on YouTube.

He does one where he draws a curved line, it goes, ‘Man in a hole. Man finds himself in a hole and gets us gets himself out of the hole, and finds himself better off for the experience.’

I think that most stories have to have that thing. It’s much more about the journey to the revelation, the journey towards the moment of discovery, rather than the moment of discovery. It is that cliche of the friends we made along the way.

When you’re writing about political things, just think about the people who are at the heart of them. What is their position? How can you complicate things for them? What does this mean for them? What are the stakes for them? What do they stand to lose? What do they stand to gain? And at their core, what is their central journey?

Stories can be about anything. And also, no one really wants to read a story that’s just your political point, if you’re going to do that, just write a series of tweets, rather than a book.

Joanna: I love that. And I think the book is fantastic.

I do want to ask you about book marketing, which is always a challenge for authors. Now, you’ve got memoir, you’ve got YA fiction, you’ve got other books.

How are you marketing this nonfiction book in a different way than marketing your other types of books?

Nikesh: I think in terms of marketing, the important thing to remember is, and I’ve seen this firsthand how little social media actually moves the dial in terms of sales. Sure, I can make a lot of noise on social media. ‘Here are some infographics that are quotes from the book, and you all know it’s coming out!’

But, actually, it’s got such a low conversion rate of sales. And that’s probably the only place where I have an audience. They’re an audience who are waiting for my angry tweets about politics rather than going, ‘I’m going to buy this guy’s book.’

Brown Baby, my parenting memoir, came with a podcast. A lot of that was just because I had a lot of conversations with other parents along the way, and a lot of things that I couldn’t include in the book, and I wanted to find a way of continuing those conversations, but also platform other people’s voices.

The essential question at the heart of that memoir was how do we raise our kids to be joyful in a world that feels bleak? Which is a thing that most parents think about, and I wanted to find a way to give those parents the space to talk about it.

And then with Your Story Matters it’s actually the other way around with that. The substack was first. What happened was, I got employed to run a creative writing course, which I love doing, it’s one of my favorite parts of the week.

But I have, in the past, been critical of creative writing courses that have course fees, and how the industry goes to those courses first to find exciting new debuts. And it’s not about the courses themselves, but it’s about how they’re prioritized by literary agents. There is a privilege in being able to afford to do with those courses, and so I thought, why can’t I just make my course notes free?

So I started a substack newsletter, and was just pushing out my course notes for that week, over the course of six months, and it quickly gained a following. My editor for Brown Baby was like, ‘Well, why don’t we just put this out as a book?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah!’ And then she and I talked about you can’t just take a bunch of substack newsletters and go, ‘Send this to the printing factory!’

We have to work out what the unifying thing about it was. My editor, the amazing Carol Tomkinson, she was like, ‘You’ve been a mentor and a teacher for so many writers over the years.’ I’ve mentored a lot of writers who’ve gone on to huge, huge things over the years, and I was a youth worker for a really long time.

I do lots of school talks. I do lots of university talks, I teach in school, I’ve taught about story, I’ve taught workshops, I now teach at Faber Academy. And I’ve taught in so many different contexts, but they’ve always had the same unifying thing which is the starting point isn’t, ‘How can I be a better writer?’ The starting point is, Your Story Matters. And you have to tell it because if you don’t, who will?’

That became the unifying thing for the book. And so that’s how that all came about. There are all these sort of add on bits I do. But I am wary that I think people place a lot of importance on having a social media profile, doing all these extra things.

But actually I do say in the book, I can’t help you write a best seller, and I can’t help you get published, but I can help you write the best story that you feel you can write.

I feel like I’m asked all the time by writers like, should I go on Twitter? Or should I have a social media profile? Should I like shout about issues to get noticed? And I’m just like, ‘No, just write what you need to write.’

You don’t have to have a profile because the writing will trump everything. You can have a million followers and be a rubbish writer and still get a book deal. But I’d much rather, if you don’t feel like things like Twitter or Instagram are natural places for you, then people will spot that and you won’t build up the following you think will help you get published and you’ll get frustrated. And it’ll take you away from the writing, and actually, the only thing you can control is the writing. So just keep writing.

Joanna: That’s fantastic.

Where can people find you and your books online?

Nikesh: On social media! Joking.

Basically I have a free Creative Writing newsletter that you are more than welcome to sign up to, nikesh.substack.com where I post up a weekly thing. I’m on Twitter and Instagram as myself.

The main thing is those of you who are writers who want a book that might, it’s not going to help you get published, it’s not going to help you write a best seller but it might just help you figure out what you’re trying to say, then Your Story Matters is out and available wherever you feel most comfortable getting books.

Be that a library, be that the dreaded A site, or be that your local independent bookshop. I make no judgment on where people buy their books because it’s so many people have different needs and different accessibility requirements and all the rest of it. So wherever you feel most comfortable getting a book, please do get it.

Joanna: Brilliant. Thanks so much for your time, Nikesh, that was great.

Nikesh: Thanks for having me.

The post Your Story Matters With Nikesh Shukla first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn