How can you create characters with unique and interesting flaws that lead into plots that will enliven your stories? In today’s interview, Will Storr explains the science of storytelling.

In the intro, German booksellers and the challenges of re-opening [The Bookseller], Facebook launches Shops meaning more opportunities for direct sales [The Verge], Facebook Live replay on writing and publishing QA, plus the most useful tools for authors.

Plus, Want to know the 6 Secrets to Amazon Ads Success? Join me and Mark Dawson on Thurs 11 June at 4pm US Eastern / 9pm UK for this free webinar. Click here to register for your free place or to get the replay.

Today’s show is sponsored by IngramSpark, who I use to print and distribute my print-on-demand books to 39,000 retailers including independent bookstores, schools and universities, libraries and more. It’s your content – do more with it through IngramSpark.com.

Today’s show is sponsored by IngramSpark, who I use to print and distribute my print-on-demand books to 39,000 retailers including independent bookstores, schools and universities, libraries and more. It’s your content – do more with it through IngramSpark.com.

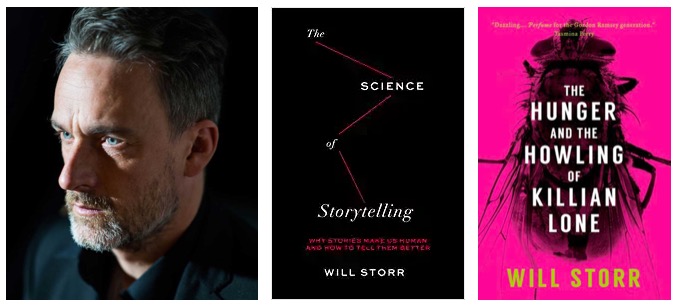

Will Storr is an award-winning writer, the author of five critically acclaimed novels, a prize-winning journalist, an in-demand ghostwriter of bestselling books, and an international speaker on storytelling. Today, we’re talking about his fantastic book, The Science of Storytelling.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and full transcript below.

Show Notes

- The hard work that storytelling is for most writers

- How we can use cause and effect in storytelling

- Giving characters depth and flaws without being cliched

- On creating original characters

- Why gossip is fundamental to storytelling

- The importance of linking character and plot together

- Dealing with character flaws in a series

- How TV has changed readers’ expectations of books

- Writing without fear of judgment

You can find Will Storr at WillStorr.com and on Twitter @wstorr. You can also check out videos from Will on storytelling here.

Transcript of Interview with Will Storr

Joanna: Will Storr is an award-winning writer, the author of five critically acclaimed novels, a prize-winning journalist, an in-demand ghostwriter of bestselling books, and an international speaker on storytelling. Today, we’re talking about his fantastic book, The Science of Storytelling. Welcome, Will.

Will: Thanks for having me.

Joanna: It’s great. And I have your book here in hardback on my desk. I also have the audiobook, it’s that good.

Will: Amazing, double, fantastic.

Joanna: First off, tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing.

Will: I always wanted to be a writer, I don’t ever really know where it came from in my family, but even when I was a kid, I was trying to write a novel when I was like eight years old. And then I came in kind of via journalism, so I kinda came in that way.

Joanna: You’ve done so many different kinds of writing, so what made you do so many different things?

Will: I suppose I became a journalist because I didn’t know what else to do. I think I started writing novels quite young and I didn’t really understand how they worked so I kind of gave up. And then I failed my exams at school and then I left school, I didn’t go to university and I worked in a local record shop.

I began a local magazine, a music magazine. And then I started interviewing bands and that turned into a job as a magazine journalist and then I moved into newspapers. And then I did write a novel, I took about four or five years writing a novel.

And that’s when my interest in the kind of secrets of storytelling in a way comes from because I fell for that rubbish that people say that you ask authors how do you write? And they go oh, the muse just descends and it just flows out of my genius fingertips onto the page. And I just don’t believe that, I don’t believe it’s true.

After I published my novel, I was moving on the stage at a literary festival and somebody asked that question to all the authors and I was the only one that they all said, ‘Oh the characters fill me up and then they just take me on these journeys.’ And I find that really hard to believe unless these people they’ve read so many millions of books that they just sort of writing that they’ve got learned by osmosis. I didn’t really make it work until I’d actually learned some craft.

Joanna: It’s funny you say that. I also know writers who swear they just take dictation. So, they sit down and their characters just take over. I’m also not like that, I’m like you.

Perhaps there are people out there who do just do that but most of us it takes some work.

Will: I think a lot of those people say they are these people that can often, and not always, but they tend to be these people that can somehow read three novels in a week. And they’re absolutely voracious readers napping all their lives. And I think that they’re still writing using kind of craft as a foundation but they just don’t realize they’re doing it because it’s like driving a car, it becomes automatic, you just learn this stuff and you start behaving in that way without thinking.

Either that or they’re writing extremely high-end literary novels that just don’t have a plan, don’t need a plan, don’t require a plan.

Joanna: I think being mindful of the story process is so important. Let’s get into the book and I’ve pulled out some quotes which I’ve underlined so much, it’s brilliant.

First of all, “cause and effect is a fundamental of how we understand the world.” And, I underlined that because even though we know that it’s something that’s so important.

How can we use cause and effect to build a better story?

Will: It’s one of those things cause and effect. I think it’s a really interesting area.

The whole book is based around the idea that the brain is a storyteller and what writers are doing is mimicking these neuro processes. They’re mimicking the way the brain creates our experience of being alive in order to kind of create a fake experience of a fake character being alive, that’s essentially the idea. And cause and effect is a real fundamental about how humans experience reality.

When something happens in our environment, we attend to it, we look at it and then we ask the question of what caused that and what’s going to happen next. And we do that in a way that no other animals do, even chimpanzee, very close relatives to us on the evolutionary tree.

It’s really important, I think, in storytelling to have that understanding that one action from a character should trigger the next action, which triggers the next action, which triggers the next action because we think in causes and effects and what difficult writing does, is it isn’t like that and then he said.

There’s this, oh, and then you need to know this thing and then this thing and then this thing. And they don’t really feel that connected, they’re just things happening next to each other.

Then we have to work out what are the causes and effects and that’s when people sometimes call that kind of stories, I think it’s the hard work they say. And it is hard work, but it’s hard work because you’re having to do the cognitive effort of tying those things together.

And it’s much more compelling storytelling takes that on board, it has characters being the causes of the effects of the narrative. It seems obvious but it’s actually in practice quite hard to do.

But I think when you really think when you’re writing, it’s that person, okay, so this has happened, how can I make everything that happens in this chapter, for example, a product of the decisions that the characters are making and to have as few as possible incidents that happening just because they have to happen?

Everything possible should happen as a result of not only the way the characters are thinking and behaving but why is it the characters are thinking and behaving that are characteristic of who they are?

So I think that’s the thing and it’s being really rigorous about trying to have everything, all the events and the drama that happens being a cause of the character’s character.

There’s a huge opportunity for creating drama when you’re working out, let’s call it chapters, it’s just how can I make everything that happens in that time level the drama, of how can we kind of show that being a product of the interesting damaged, flawed characters that we’re trying to explore.

Joanna: Let’s go into that damaged flaw there because I feel that obviously there are books where there’s no damage, no flaws, just cardboard cutouts. But then there are also books where they’re kind of obvious, cliche, damage and flaws.

How do we give our characters depth without becoming the cliched alcoholic policemen or whatever?

Will: I really think that the answer to this is absolute specificity. When I’m teaching, that’s the main thing I’m doing even in the week-long course is going over and over again on who is your character and how can we, before we do anything else, define their flaw with absolute precision. So it’s precise.

It’s not just all that because what people always say is, tell me about your character, what’s their flaw? How would you describe the flaw?

And for some reason, most of them would say they’re very controlling. And that’s not good enough because you can be controlling in a million different ways, everyone is controlling, everyone is trying to control stuff, how are they controlling?

It’s making that extra leap and that’s when you get really interesting stuff and people say things like, well, how do they try and control the world? They could be over there trying to tell kind of tall stories or they are trying impress people with a kind of certain strategy.

What you’re trying to get to is a flaw that’s specified and precise enough that you can then imagine your character behaving in any particular situation.

So in the book, as I was writing the book, it was all during that awful Brexit stuff and there was all this chat about Theresa May. I read this profile of Theresa May when everything had gone wrong under her watch. And somebody who knew her said, Theresa May’s problem is ‘she always thinks she’s the only adult in every room she goes into.’

I said that is brilliant, that is exactly what we’re talking about because if you define someone’s flaw with that precision, they always think that they’re the adult in every kind of situation they walk into.

You can take that Theresa May character and put her in any kind of genre, kind of story, any kind of literary story and you can imagine how she’s going to behave. And that’s what we’re trying to get to.

We’re trying to get to a character that just comes alive in your imagination. And as I say that really comes with that precise thinking is that the vague thinking, either an alcoholic, they’re a bit sad, their mum didn’t love them, none of that is good enough.

Joanna: It’s a tough one because I feel like that can lead us to potentially very internal writing, whereas a lot of listeners, I certainly, I write thrillers so I do need a lot of external action as such.

How can a flaw lead us to action in a plot as well as interior struggle and conflict?

Will: The action is the stuff that’s going to directly cure the flaw. So if you’d know what your action is going to be, then you reverse engineer it and go, okay, so what kind of person, what kind of flaw, what problem would be solved by this action which I’m going to design?

A good example, you’re right, that obviously, story setting all exists on this huge spectrum, and characters have a variety of levels of depth depending on the kinds of stories that you’re going to tell. But even broad, thrillery, action-filled stories tend to revolve around a character flaw.

In ‘Jaws’ for example, two million-selling book and classic film that’s based around this guy, Brody and his flaw, his very simple flaw, he’s scared of the water. We find out in that book and in that film that he has his absolute childhood dread of the water and to such an extent that when he gets the car ferried over to the beach community that he lives in, he stays in it, he can’t even get out of his car.

So let’s say he’s absolutely terrified of water, he thinks if he goes anywhere near the water, he’s going to die.

He’s a police chief in charge of the security of a coastal town. And then crash, bang, wallop, a great white shark arrives and starts eating everybody. All of that action around that shark is specifically designed to force Brody to confront his phobia, his flaw, his fear of the water and cure it.

The whole plot is structured around that flaw. So it begins, the shark comes halfway through the midpoint, he finally gets the courage to go into the water. And then the very final scene in the film, it isn’t the shark blowing up, it’s Brody swimming back through the water.

And the last bit of the dialogue before it fades to black is him saying, ‘I used to be scared of the water, I can’t imagine why.’ So even ‘Jaws’ which is all 98% action, action, action, is actually structured around a character with a character flaw.

Joanna: That is a great example. I love that example. That was fantastic.

You’ve got some interesting things there in terms of flaws. I’m now standing here thinking of my characters and my character flaws and one of the things I think is that research because we often tend to think about flaws that we might have ourselves and certainly the main character in my ARKANE series, she shares some of my flaws.

What is a good way to research different flaws to make our characters more original rather than, as you say in the book with bolt-on quirks.

Will: Again, it’s about that precision and it’s just about looking out for stuff, like that Theresa May one, was just something I read in the newspaper and it leaped out to me. That’s a really great description of a flaw, of a very specific character flaw that you could turn into any kind of character.

I was watching ‘The South Bank Show’ recently was interviewing Arthur Miller and, what’s his name, was asking him about the Willy Loman play ‘Death of a Salesman.’ He was talking about the character and he said that his idea was that he just believes in that capitalistic success and the idea that when you die, you’re going to be weighed on a scale, just like God is to weigh for sin, now you’re weighed for success. And I just thought that is exactly what we’re talking about.

You could take that idea that I’m absolutely obsessed with success and being weighed on that scale. You could take that and apply it to any kind of character in any kind of story because it has that level of specificity. So it’s just being on the lookout for these.

Once you were on the lookout for them, be brazen about taking them because you’re not stealing from Arthur Miller by taking that idea and adapting it into your own story, it’s just you’re not stealing from Theresa May by taking her one and putting it into one of your characters.

I think it’s being on the lookout and even in your kind of personal life and your family life you can think what is it about this person that upsets me or winds me up or that they keep getting wrong? If I could really define it in a specific way, how would I define it?

Then you get a nice collection of potential characters that are encoded in these very specific ideas. And the magical thing about this, at least when I’m working through it in my workshops, is that they start off with this one or two-line sentence lines on a bit of paper but when you run these ideas through all the demands of a really gripping, relentless plot they become incredibly complex and incredibly nuanced and incredibly original.

It’s this weird paradox where you start off with this quite reductive but specific idea but you end up with really complex and original characters in a way that you don’t end up with complex and original characters when you start off with vague stuff about alcohol like they’re an alcoholic detective inspector or whatever.

Joanna: Another one!

Will: Because where do you go with that? You can’t imagine that. I could imagine an alcoholic detective inspector and lots of scenes and they’re glaring and they’re grumpy and that’s what we get every time we watch a Scandi thriller, it’s the same character, so again it’s being precise.

And another thing that happens when I’m teaching is that not only a character that is quite vague alcoholic detective inspector but they begin with too many different ideas, they’re this and this and they’re this and they’re this. And again, I think that vague thinking about character is really the enemy because it’s easy to think that if I give lots of ideas to my character then that’s going to add up to a complex character but actually the opposite is true weirdly.

Joanna: That’s great. So coming back to drama, which you mentioned before, the dramatic question.

What is the dramatic question and why is it so important?

Will: I think this is if there is such a thing as a secret of great storytelling, I already think it’s this. And it goes back to the very roots of storytelling.

In the psychological sciences, the current theory of why humans evolve language is to swap social information. We’re these apes that live in these highly co-operative tribes and we’ve worked out how to divide labor and communicate and work as teams, and that’s how we’ve dominated the world. But in order to do that, you need to control people.

So we evolved language in order to basically swap gossip, to tell gossipy stories about each other. And then if people came off badly in these gossipy stories they’d be punished and if they came off well they’d be celebrated and that’s how we kept our tribes running. Gossip lies at the very roots of why we even speak, let alone the roots of storytelling.

If you think about storytelling, any kind of storytelling, whether it’s little news piece about Meghan Markle or it’s Anna Karenina or whatever, or Jaws even, there’s a gossipy element to that stuff.

Even with Jaws, “He’s in charge of this beach community and he’s scared of water.”

The fundamental purpose of story is to work out who is this character? When the chips are down, when their back’s really against the wall, who are they? Are they a good person? Are they a bad person? Are they flawed? And if they’re flawed, how are they flawed? And how are they going to fix that flaw?

That’s the dramatic question for me is who is this character? Who are they? It’s really fundamental to great storytelling?

Because it’s fundamental to gossip, which is what all storytelling kind of leans towards. And I think that’s why I like to start off with that idea of that flaw because then the dramatic question gets turned into not just are they a good person or are they’re a bad person, but what is their flaw and are they going to fix it?

Every single dramatic, really dramatic scene in Jaws is asking that dramatic question of Brody, saying, is he going to be the old Brody who’s scared of water? And sometimes he is, he’s terrified, he regrets going down to sea, he panics. Or is he going to be big enough to overcome that flaw and destroy that shark?

The most dramatic scenes in Jaws are the ones that are specifically asking that dramatic question, who is he? Is he old Brody or new Brody? Good or bad? Weak or strong?

So it’s that really and they come to an understanding that that’s the real gold of storytelling, that’s what I think that we’re really moved and entertained in a really profound way that kind of pure action often doesn’t get to.

Joanna: You gave a really good example of Lawrence of Arabia in the book which even if people haven’t seen, I think everyone now has that picture in their head of him in his outfit.

Maybe talk about that one because I found that a really powerful example.

Will: Lawrence of Arabia is a really good example of, say, if you’ve not seen the film or you’ve not seen it for a while, it’s a three-hour film but in my class, I’ve actually edited it down to a 60-minute version, which just focuses on that dramatic question.

What happens at the beginning of Lawrence of Arabia is you meet this very naive, fey, cocky, arrogant, young soldier who’s showing off, putting a match out with his fingertips and refusing to salute to his sergeant major, or whoever it is and being sarcastic.

You get the sense of this flaw which is somebody who really believes that he’s this cocky rebel and he thinks he’s better than everybody else because he’s got this rebelliousness. So that’s fine, that’s his flawed character.

But then what happens is you take that flawed character, that character that believes that my rebelliousness makes me superior, makes me extraordinary and you put them in a war situation. And that is a situation that’s perfectly designed to test that idea.

That’s what you see in Lawrence of Arabia in it’s most gripping, iconic scenes are asking that dramatic question.

And that dramatic question in this context is, who are you, Lawrence? Are you ordinary or are you extraordinary? And sometimes in the film he believes he’s extraordinary when he kind of singlehandedly leads the Arabs into battle against the Kurds and he’s hailed as this God, he believes that he’s extraordinary and it feeds that flawed idea and he becomes monstrous in his idea that he’s extraordinary.

But then other things happen, like he’s forced to kill somebody, he loses somebody down in some quicksand. And then he realizes that I’m actually just ordinary, and he tries to quit the army and then the army will go, no, no, you can’t quit, you’re extraordinary, and he goes, actually, you’re right, I’m extraordinary.

And then what you see if you look at it in terms of these fundamentals is that Lawrence of Arabia basically the whole plot is asking that question. It’s all revolving around that simple, dramatic question, are you ordinary or are you extraordinary?

Because it’s a tragedy, he doesn’t overcome his flaw, he just believes he’s more and more extraordinary until he becomes a monster. He becomes this homicidal maniac and the film towards the end, we see a very iconic scene where he lifts the bloody dagger and he looks at his reflection in it with kind of horror as if he saying what have I become?

Joanna: I think my feeling with the book and what you’re talking about with characters is that a lot of writers can come up with a plot and come up with characters to put in a plot. But what you’re talking about is to tie the two together.

So Lawrence of Arabia and Jaws as you say, have both got a lot of action. They’ve got fight scenes and creatures and death going on but they are, as you say, at heart, they’re about character. I think those examples are really good at linking the two together.

Will: And I think that’s the number one thing.

The one problem that I wanted to solve with the book which I’d seen in my classes over and over again is exactly what you just said, is that the characters and the plots are unconnected.

And I think that’s a really fundamental problem. You even see that problem expressed in the big movies that get made and books that get published, things that pass the bar in that way.

I think that’s a real shame because a story should be like life and in life, the stories of our lives, of course, intimately that they’re not just connected to who we are as characters, there are a product of who we are as characters. So you can see the goals of our lives are the plots of our lives, and the obstacles that we overcome in order to try and achieve those goals are our stories, they are our narratives.

But our goals and our obstacles are very often a product of who we are. The things that we want in our life, the things that we dream of achieving are a product of who we are.

The obstacles that we encounter in our day to day lives tend to be the same problems over and over again because they’re problems that stem from our personalities, from things we get wrong in the social world. So a plot is a product of character, plot comes out of character and plot tells us who the character is.

One of the ways that I like to think about it is that your plot is designed specifically to plot against your character. So you’ve got this character with this particular flaw, in the most simple sense, Brody, who’s scared of water. And the plot is there to connect absolutely with that flaw and test it and test it and test it and keep testing it until they either change, they transform or they, like Lawrence of Arabia don’t change actually, so double down on their flaw and just get worse and worse and worse and worse until they explode.

Joanna: I love this idea, but I feel that it works for a standalone or in the film sense a film rather than say a TV show. I’m going to write book 11 in a series scene and series characters, I mean take Lee Child’s Jack Reacher, for example, or James Bond, they have flaws but they can’t be resolved at the end of the episode or the end of the book because there has to be another book. And those are actually the best selling stuff out there are the series.

How do we deal with a series rather than a standalone?

Will: You just don’t cure them. So I think go really, really, really back to brass tacks. The way I think of it is, what is a story? What are the minimal conditions to have a story?

For me, it’s two things. You’ve got an external event, something that happens in the external world, but it happens to somebody and it changes them in some way, but it doesn’t have to change them in a transformational way like you get in an archetypal kind of hero story. It might just change the way they see the world, it might just change the mood they’re in.

If you take a Raymond Carver short story or Kafka short story, that’s all that happens often, is that something happens to a flawed character and it changes their perspective in a certain way. And it’s said in this almost undefined way that’s kind of slightly moving.

Episodic TV is no different. If you think about a show like ‘The Archers’ which has been going for 60 years, they say it’s the longest-running kind of episodic story in the world. What happens in a show like “The Archers’ in like a soap opera is you’ve got these flawed characters and the story events keep happening at them and keep being thrown at them and they keep being tested and they might change in little ways but they never really change completely. And then you just keep throwing story events at them again and again and again and that is an episodic TV show. So that’s a soap opera, it’s also a sitcom.

If you think about the classic sitcom characters, whether they’re Fleabag or David Brent or Basil Fawlty, they don’t change and actually the fact of they’re not changing is a source of the comedy. But what does happen is that every episode, a new story event is turned up, a new thing is turned up and they test their flaw, exposes their flaw.

And because it’s not like a 90-minute Hollywood movie or a standalone novel, they don’t go through this big transformational thing but they do change, even if it’s only kind of a very shallow change and not necessarily personality change, it does cause them to kind of enact their flaws in that way.

I think you’re absolutely right, of course, James Bond never transforms but I don’t think transformation is a prerequisite of storytelling. And as you rightly say, it would be death to episodic TV because you’d have nowhere to go.

Joanna: Unless you have Game of Thrones; so many characters that you can do all these different things.

Will: Transform them and kill it and they bring another one in. So I think one of the things that I wanted to do when I’ve read lots of other books about storytelling, one of my problems with them is that I felt like a lot of them are very prescriptive and they say, this is a story and this isn’t a story. If you haven’t got these elements that it’s not a story.

I just think that’s crazy, there are so many different kinds of storytelling and they’re all as valid as each other.

To me, ‘Love Island’ is as valid an example of storytelling as anything by Tolstoy.

It’s all storytelling, it’s story events happening to flawed characters and we enjoy seeing them react.

Joanna: That is such a great example because I swore I would never watch ‘Love Island.’ And then my sister said, oh, no, you’ve got to watch this because I want to talk about it, this is last summer. I watched an episode and I was like, oh, my goodness, this is so addictive.

You started by mentioning gossip and ‘Love Island’ is just gossip, isn’t it?

Will: It is but just as I say all storytelling is, and when ‘Big Brother’ was on, I was a massive fan of ‘Big Brother.’ And I think because it’s storytelling.

Back in the days of Charles Dickens, he would put out these new episodes of his kind of gripping stories in the newspapers and people would be obsessed with them. ‘Big Brother’ and ‘Love Island’ are the modern Charles Dickens’ mass-market storytelling.

As I say the producers are really smart and the editors are really smart, they cast their characters, they see that they’re flawed. They edit them in such a way to kind of amplify their flaws and define them by their flaws. And then they keep throwing story events at them.

In ‘Big Brother’ it’s the tasks, in ‘Love Island’ it’s throwing in a new character to test their love, to test their commitment. So it’s storytelling and you can condescend to it as much as you want but it’s incredibly successful storytelling.

It’s storytelling that grips literally millions of people every year and they turn it around in a day, every day there’s a new hour. So I really take my hats off to those people.

And I honestly, for me, there’s no kind of enormous binary categorical difference between what ‘Love Island’ doing and what novelists are doing, it’s all story events happening to flawed characters.

Joanna: Do you think the publishing industry is able to keep up with the way that TV and films and social media are changing the way we expect storytelling? Because it does seem to be much faster now.

Do you think that TV has changed readers to want a different thing from books?

Will: I think it is faster, I think people are far less patient. Especially post-internet, they need to be gripped straight away and that’s really hard. You’ve only got to go back and read I mentioned Charles Dickens, that was the ‘Love Island’ of its day, but now it feels so slow that you’re reading and you go you know what? Come on, stop describing this man’s beard, come on, so I think we’re all a bit guilty of it. I think people are really story-hungry these days, they want stuff to happen straight away.

And it’s into that slightly frustrating thing that happens on television especially in documentaries where you turn on a TV show and they spend the first five minutes telling you everything’s going to happen and then they start. And it’s like, ah, I don’t know either because they’re so worried about you. They’re so concerned about telling you don’t worry, stuff’s going to happen, that they kind of give away all the entire sequence of events before the opening credits have come.

I think it is very real that people are becoming far more demanding in terms of story, but it just means storytellers have to kind of up their game really. And I think novelists especially literary novelists, are the ones that are becoming kind of most exposed by that because I think that there’s a certain amount of self-indulgence in very literary storytelling, spending six pages describing the interior of somebody’s wardrobe or something like this. And I think that you’re going to get away with that kind of stuff kind of less and less and less.

Joanna: Although that’s a great example because on the other hand, you’ve got Instagram stories where people are showing what’s on their bookshelf or what’s in their wardrobe.

The story of the day might be what’s inside someone’s closet but again, that feels like gossip.

Will: It’s gossip. We’re highly social animals, so we’re always interested in what is going on other people’s heads. What is going on other people’s closets? What are they like?

It’s that dramatic question. Who is this person and who are they really? Because even though they’re trying to present as but who are they really? That’s what we’re really interested in when we’re looking at stories on Instagram.

The person showing us their wardrobe might think they’re presenting in one way but generally, there is going to be a much more complex narrative going on in our heads as we’re thinking, ‘Oh, what do they think they’re doing?’

And so the judgment is often not what the presenter is expecting because we’re curious and we want to see the whole picture rather than the one that’s being presented. And again that’s also storytelling. That character at the beginning presents in a certain way and by the end of the story, we got to know them a whole lot better.

Joanna: People don’t want the polished, perfect, totally successful person, that’s not what they’re interested in.

And your novel which I started reading actually last night, well one of them, The Hunger and the Howling of Killian Lone.

The reason I downloaded it, it’s described as part sinister fairy tale, part Gothic horror, which is totally down my street. But that’s interesting because that immediately says something about you which people just didn’t three minutes ago, is that you’ve written this type of book. And I also write this type of book so I get you.

But it’s interesting because, and again with people writing romance or sex or violence and these are dark things and we read in order to vicariously experience it.

As writers, how do we incorporate the darker side of ourselves without suffering from this fear of judgment or fear of exposure or self-censorship and all these things that make us want to hide the darker side?

Will: I think that’s one of the gifts of fiction, isn’t it really, that you can tend to hide behind the characters that you’re writing. I do suspect when I wrote that novel, I really didn’t think it was about me at all, I didn’t even notice that his name is mine just with one letter switched, literally it didn’t occur to me that Killian is William until I finished the book.

I think that’s what novelists are often doing is exploring their own problems and exploring their own worries and concerns and anxieties, but in a safe way because it’s in fiction so we can run these simulations of what might happen if our worst fantasies came true in a safe way.

That’s probably why we go to stories in the first place, like evolutionary kind of speaking. But one of the purposes of tribal gossip was to we tell stories and then in hearing, in understanding the stories and seeing how other people reacting to them, your understanding how should I be living in the world? What is good behavior in this place and what is bad behavior? What kind of behavior is hailed as heroic, what kind of behavior is leading to people being punished? And how can I then apply that to my life?

One of my favorite quotes about story was by a radio producer whose name escapes me. And he said that every story is an answer to the question, how should I live my life? I thought that was really, really profound and a really lovely way of putting it.

I think that applies to writers as well. You’re trying to work yourself out a bit I think in the process of writing and also in the stuff that you’re reading. I noticed that people, especially these days, feel like they want to apologize in a way for if they’re caught reading books by people like them as if it’s sort of cliquey and narrow-minded.

But I think it’s perfectly natural that women most of it if you know that women like to read books by women and working-class people like to read books by working-class people because they’re more meaningful to us and where we are in the world.

I like reading mid-century American novels about middle-aged men having problems in their lives because it resonates and you feel partly that you should apologize for reading lots of books about middle-aged men, but why? I don’t think that’s something to apologize, I just think it’s natural.

Joanna: I must say most of my books have main characters who were women in their late 30s, early 40s doing cool things in the world.

Will: There’s nothing wrong with that. I think it’s very natural and actually it’s much more difficult for you to suddenly try writing a Charles Bukowski kind of character because it’s like, where would you begin and why would you even want to bother doing that?

Joanna: I’d have to drink a lot. Clearly. And take a lot of drugs!

Will: Exactly.

Joanna: We don’t want to go there, but no, it’s fascinating.

As I mentioned at the beginning, I’ve got the book in hardback and also audiobook, which you narrate and it’s really good.

I’ve really enjoyed it, you have a great voice and a great attitude in it. I’m interested because I’ve narrated some of my own nonfiction and many people listening are interested in that.

How did you find that narration process and any tips?

Will: I found it really hard. How did you find it?

Joanna: It is. It’s really hard work, right?

Will: Yes. I thought this should be a fun few days. I think it was like two days or two days you get or maybe be a bit more, I don’t know, I can’t remember. But it’s really hard and to say, I think that the first thing like very practical thing is that I was embarrassed because on the first morning the producer could hear my stomach rumbling and he kind cut in and went, ‘Have you had breakfast, Will?’ And I’m like, no.

And he goes, ‘Do you want to go and get yourself some breakfast in Sainsbury’s?’ No, no, I forgot. So I had to interrupt the session because my stomach was rumbling. That was really embarrassing and unprofessional. So that was have breakfast is of great relevance here.

But I think the other thing that I found worse was, I don’t know how you found it but by the end of it, I hated my book. I was like, I never want to see it again and never want to hear it again, it’s terrible. No one’s going to like this, I don’t know what it is but it’s like I really, really fell out of love with my book after that.

It took me a while to get over the audio narration. And I think I’m going to do my next book but I know now that it isn’t just really fun. Because honestly, you think, oh, I’m reading my book out, I’m going to be so proud. I’m going to feel really great about myself but I found the opposite, you see all the flaws, you see all the problems.

Joanna: But I’m interested because obviously I’ve reacted very positively, I love the audiobook.

Have you had feedback from readers that have made you happier?

Will: The audiobook’s done really well. I don’t know any specific figures but I know that for one day last month it was the number one bestselling book on Audible.

Joanna: Oh, wonderful.

Will: Which is bizarre. My publisher promoted it so it wasn’t out of the blue but it’s a niche book. So I was baffled by that but very pleased. And yes I do know the audiobook has done really well which is why I know that I’m going to have to do the next one too, I can’t get away with giving it to an actor.

But yes, so I’ll definitely be doing it again and maybe that’ll make me feel a bit better about it because it wasn’t you feel very self-conscious like I don’t know, I felt at times like I was…you’re worried, am I over annunciating, am I being like a really over-excitable ‘Blue Peter’ presenter.

Joanna: I quite like that though.

Will: You gotta keep the energy up. So I’m glad I did it in the end because it’s been a really popular format.

Joanna: Fantastic. So is the next book a book for writers as well?

Will: No, the next book is about status.

Joanna: That sounds interesting.

Will: There’s a little bit in the story book about how important status is to people and in a way, you can see stories as a kind of status game of status really, very often at the beginning of stories when the protagonist is somehow low in status.

There’s always that bit a detective inspector, police procedural where the DA gets taken off the case. They’re always being pushed out and they learn through the trials and errors of the plots of how to become heroic and win status. So, I write about that in the story book in that context but I’m turning into a full-length book which is going to be called The Status Game and that’s going to be hopefully published next year.

Joanna: Writers are obsessed with status and ranking.

Will: The first book I read in my research was Alain de Botton’s Status Anxiety, it’s the only other book on status. So, I thought, well, I’ll read it and see what he came up with. Because I read it when it came out and I’d forgotten it.

He’s mad. He seems to think that status is an invention of capitalism. And one of his solutions, one of his suggestions if you’re suffering from status of anxiety is be like an artist, be a writer. Because if you think about the writers, they live in these garrets and they weren’t really worried about status, they were just happy being poor and writing. And I just thought, have you ever met a writer? That’s not true. Being a writer is not a cure for status, absolutely not.

Joanna: If you do want to be in your garret, it’s competitive as to how poor you can be!

Will: Exactly. That is the nail on the head. Look at how poor and windy, my garret is much windier than your garret.

Joanna: Absolutely. Okay. So, tell people where they can find you and the books and everything you do online including your courses.

Will: So the best thing to do is to go to my website WillStorr.com or TheScienceOfStorytelling.com which has all the course information and some YouTube videos and quick start YouTube videos.

If some of the stuff we’ve been talking about sounds useful, I’ve got a five-step guide to beginning using these techniques about specific characters and how to build a plot. And I specifically use that Jaws plot in the video as well. So that five-step plot, which lots of sort of genre books and bestsellers often have.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, thanks so much for your time, Will, that was great.

Will: Thanks for your questions. I really enjoyed it. Thank you.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn