On July 4, 2020, Kory Shrum received two phone calls. One from her uncle, saying her mother was found dead in her bedroom from an overdose. A second from a homicide detective saying he believes it was murder—and her uncle is the suspect.

In this interview, Kory talks about how she turned her trauma into a true-crime podcast and memoir and how writing helped her process the experience.

In the intro, 6 ways that this is the best time in publishing [Publishing Perspectives]; Content Creators deserve a bigger slice of the pie [Kristin Nelson].

Today’s show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, where you can get free ebook formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Get your free Author Marketing Guide at www.draft2digital.com/penn

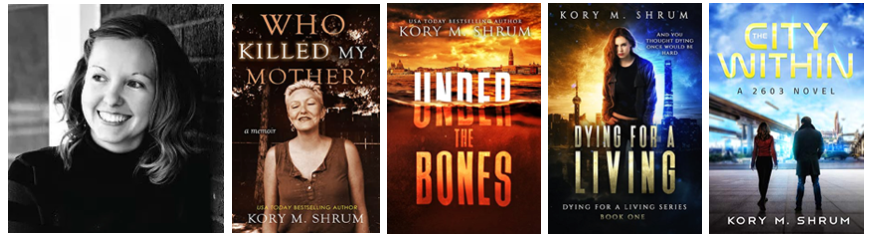

Kory Shrum is a ‘USA Today’ best-selling author of science fiction, fantasy, and thrillers. She’s also a true-crime podcaster. Her latest book is a memoir, Who Killed My Mother?

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Studying poetry as a way to develop skills for fiction

- Making the choice to write a memoir about a very difficult subject

- Why sharing feelings is so important in memoir

- Tips for healthy ways to experience emotions while writing

- Seeking the truth in memoir and how memory plays a part

- Telling one story in multiple formats; podcast, book and audiobook

You can find Kory Shrum at WhoKilledMyMother.com and on Twitter @koryshrum

Transcript of Interview with Kory Shrum

Joanna: Kory Shrum is a ‘USA Today’ best-selling author of science fiction, fantasy, and thrillers. She’s also a true crime podcaster. And her latest book is a memoir, Who Killed My Mother? Welcome, Kory.

Kory: Thank you. I’m so glad to be here. I have been a fan of yours for years. I’ve been stalking you on the internet for years. And then I tried to steal your assistant, Alexandra. So it might be getting a little creepy at this point!

Joanna: I really appreciate your support. And also what we were saying before we started recording that, because of our connection, I’ve discovered your novels and our readers, but we share some readers in the fiction space.

I think a lot of this stuff is about connecting with people and people who are like us in some way. We’ve never met in person, maybe we never will, but it’s so great to connect across the world, isn’t it? So let’s start.

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing.

Kory: I had loved books and writing and everything about the world of literature all of my life, but I didn’t really get serious about it until college. I changed majors so many times because I had so many interests. Like you, I’m a multi-passionate, creative, and there are just so many things that I love about the world. And I love learning.

I think it was like the fifth time that I went to my advisor’s office and was like, ‘I’m thinking about changing my major.’ And she was like, ‘Kory, Kory, Kory, listen, I just want you to go down to this office and take this test, and it will tell you what major you should be.’

Joanna: Cool.

Kory: And so I was like, ‘Okay.’ Yeah. So you take a test, and it matches your interest to a field. And so I went down there, and I took the test. I matched an English major with, like, 94%, or something ridiculous. It was really clear that I should be studying literature, books, and things.

I already had a creative writing minor at that point that I had basically completed, but I didn’t think of the English major, because I was like, ‘Are there English major jobs?’

But it turns out there are, and so I completed that. And then I went on to get an MA. And then I had to make the decision if I wanted a PhD in creative writing, or an MFA in creative writing. And you don’t really need to do this in the real world. But it’s like what people will tell you, ‘Oh, if you want to be a writer, get an MFA.’ And so I did that.

I chose the MFA because the Ph.D. seemed more like literary theory, whereas I just wanted to learn how to write really well. And MFAs are studio degrees. They want you to be writing.

But the issue is, is that I like a lot of genre fiction and genre tropes. And it’s not as accepted in academia as literary fiction. They have the high-minded…you could see it in capital letters, literary fiction. And so I was like, ‘Well, what am I going to study?’ Because I can’t really do vampire novels. I’ve had a teacher in class say, ‘I will accept no vampire novels this semester.’

So I chose poetry instead. Because I thought, well, if I could master poetry, that’s a mastery of description, and language and flow. I think that that would really help my fiction writing as well. I don’t think it would be a waste of my time to learn how to write poetry.

I chose to study poetry for my MFA. And it was great, I had amazing teachers, it was a wonderful experience. It was the first time in my life where I was around a lot of creative writing people who were really affirming to what I wanted to do. I was still writing my genre fiction in class, so I was clearly still doing both at the same time.

I graduated, I started teaching. That’s what you do, if you have an MFA.

The primary job you would get is teaching, and I started pitching agents. I got a good agent, a really reputable agent. She was with me for four years.

I gave her three manuscripts in that time, but she couldn’t sell them, because even though we would get really nice feedback from all the big publishers like, ‘We really like Kory’s writing. This is good stuff. We just don’t know where to place it.’ Because my fiction is very cross genre.

Dying for a Living, for example, was the book she was shopping around. And I still don’t know exactly where you would put that on the shelf. Is it a mystery? Is it a zombie novel? But it’s not a zombie novel, because they’re not the zombies we think of. It’s really unclear.

From a publisher perspective, they want to know exactly where to put it on the shelf. So she couldn’t sell those.

After about four years, this is when Argo-Navis, this self-publishing platform that, for a hot minute, I don’t know if they’re still doing it, they were using it to self-publish books they couldn’t sell. So my literary agency was like, ‘Well, let’s do your books through Argo-Navis.’

But it was essentially a self-publishing platform, but the agent got 15%. And I was like, ‘Why would I do that?’ Well, also because, at the time, I didn’t know nearly as much as I know now about self-publishing.

Now, of course, it seems like an easy question; of course, you wouldn’t do that. But then the only deciding factor was that I had worked for several years, when I was at my MFA program, in a small press. New Issues Press is attached to the school I went to, and I was a layout editor for them. I also took a publishing class.

So, because I worked at the press, I was very familiar with the whole book publishing process, how you get the manuscript, how you edit the manuscript, how you turn it into a book, how you get it out there into the world. So I was like, ‘I already know how to do that. Why would I pay her 15% if I’m going to have to do it myself anyway?’ So it just didn’t make any sense to me.

So I broke up with my agent then, and just focused on writing as many books as I could. I finished out the Dying for a Living series while I was teaching as an adjunct professor. And then I had about 10 books out when I left to write full-time. That was 2018.

After that, I’ve been putting out about four books a year, about three novels and a book of poetry since, and I still also read poetry submissions for the ‘Los Angeles Review.’ That’s my writing life. That’s what it looks like now.

Joanna: That’s interesting. I just looked up Argo-Navis, because I hadn’t heard of it. So 2012, 2013, that was when they were doing that. And at similar time, I think, it was Amazon White Glove was a similar thing where agents could basically self-publish on behalf of authors and take a percentage. There are so many of these things that come and go.

Let’s get into your latest book, which is a true crime memoir. And it is very personal. It is called Who Killed My Mother? And it is that, which is difficult, I guess.

Why write this incredibly personal book, when it must have been very difficult to write?

Kory: Well, I mean, you say, ‘Why do it?’ like it was a conscious choice. But, to be honest, I was so consumed by the idea of doing it when it happened.

The premise is that on July 4th 2020 I received two phone calls. The first was from my uncle, who said that he had gone into my mother’s bedroom and found her dead, and he thought she had died of an overdose, which was surprising because she had drug abuse issues in the past, but she had been clean for a long time.

Mostly, she couldn’t do anything because her health had become so poor. Not that that necessarily stops some people. But in her case, she was just too ill to do anything. So I was surprised, but I wasn’t horrified, or I wasn’t suspecting anything at the time.

But later that day, I got a second phone call from a homicide detective saying that he thinks it was foul play, that something bad had happened, and that he suspected my uncle, and that they were arresting him and taking him in.

So now I was very confused and I was upset. And I was like, ‘What really happened to her and like, what went down in that house?’

I remember waking up that night. I couldn’t go to sleep. It was like 3:00 in the morning. I get up, I go down to my office, and I’m kind of just pinging around in my home office I’m rereading the stories I wrote about her in college about these other near death experiences where she had almost died because of his violence toward her and stuff.

I was just so captivated by this idea that I have to sort through this and I have to understand what has happened. The only compulsion I had was, like, ‘Well, I’m going to have to write it down.’ Like, ‘I’m going to have to write down everything that happens going forward.

But I’m also going to have to write down what happened in the past to make sense of this life that I had with her.

Because it was also that I couldn’t really understand why her life had ended like this. I had to look back and understand her life in its entirety.

So it’s not like I was like, ‘Oh, I think I’ll just do this.’ It was more like I was completely possessed and compelled to organize her life, because there was so much confusion around how she died that I thought the only way to gain clarity would be to write my way through it.

That’s basically what I did was I used it as a tool to make sense of what had happened.

Joanna: I think dealing with these terrible life situations, writing is obviously a way we can help ourselves, but you chose to go further and publish it. And we’ll talk about podcasting it as well.

Where is the line? I’ve read the book. It’s a great book as a mystery. As you said, you were compelled to write this.

Where’s the line between writing as therapy and writing for publication?

Kory: Fortunately, at this point I’ve put out 22 books or something like that. So there is some division in my brain I can switch back and forth to being Kory the publisher, Kory the editor, Kory the person with a lot of feelings.

I can be each Kory when it’s time to be each Kory. And I think that’s just come with…I don’t even know how long I’ve been writing now…18 years of experience of doing it. So it might make it easier.

But, in essence, it’s just that I wanted to be honest to the experience. So you said you’ve read the book. You probably are well aware of the fact that there’s a lot of emotion in it, but not in an overwrought, I don’t think, dramatic way. I don’t feel like it was overdone. But I do keep you very close to what I was feeling at the time that things happened. Would you agree with that, or you want to say no?

Joanna: Yes, I think you did.

For people listening, for people who want to also write a memoir, you have to know where the line is between ‘this is my therapy, and this is for publication.’

Kory: Right. So what I mean by that is, I want you to step into your feelings as a writer. I guess I’m thinking of the phrase, ‘Feel your feelings.’ You always hear, ‘Feel your feelings.’

I used to get so mad when people would be like, ‘Well, you just need to feel your feelings, Kory.’ I’d be like, ‘What does that mean? Of course, I’m feeling my feelings. My feelings are so present, how can I not feel them?’ But I think what they’re talking about is getting really into the experience of an emotion as a way to process it.

That connects to what you’re saying about feelings as therapy, because that’s what you do in therapy. You step into your feelings, you feel your feelings, you process it. And if it comes out raw, like in a messy way, if it’s not worthy of publication at that time, that’s okay. That’s what editing is for.

I have a wonderful editor in the UK, his name is Toby, and he would be able to clean that up. But, fortunately, I’d already done so much rewriting at the point that he saw it, it wasn’t an issue. But it’s not unnatural, when you’re experiencing what you’re going through, to just put it on the page however it comes out, because you want to be authentic with what you’re feeling.

The connection between people is what I think makes memoir special.

We read memoir, because we want to experience other people’s lives or experience other things that people have gone through. And when we do that, we’re connecting with their experience, their emotional experience.

If you’re distanced from doing that, I think the experience won’t be as rich for your reader. So absolutely step into it. You can always go back and do the editing and the publishing part later with a more critical eye.

It’s the same as fiction, at least it was for me, in the sense that, ‘If this doesn’t work, or this detail doesn’t work…’ So, for example, I kept really good records as the investigation unfolded about, who said what, at what time.

But sometimes, I wrote a piece of dialogue that was literally from a text message or something on the page, and it just looked ridiculous, because when you text, you shorthand or you talk in a very contextual way, and it doesn’t work.

You can rework that for flow, or you can drop that piece of dialogue altogether, if it’s not doing anything for your story. The mechanics can always be sorted out later, but I absolutely think you can stay close to your feelings.

It can be therapy, but it’s also, at least for me…and maybe it’s just because I’m a thinkie person. I’m an INTJ, so I’d lead with thoughts. But for me, it’s more like sorting details and alleviating confusion than sort of drowning in emotion.

Joanna: I agree with you on emotion being a really important part of memoir. The difference between memoir and autobiography as well is the first person POV but also the emotional connection.

You write about death a lot. You’ve got this ‘Dying for a Living’ series, and your books have death in.

How else did your fiction writing help the memoir in terms of both with cliffhangers and the mystery side?

Kory: Because I wrote the memoir, actually, first as a podcast, the chapter endings were a bit cliffhanger-y because I wanted you to then want to listen to the next episode. And, fortunately, it worked out that way just because the investigation was somewhat slow in the sense, so I was always kind of on the verge of a cliffhanger. I also didn’t know what was going to happen.

I utilized that to my advantage. I don’t know that I did anything particularly insightful from a technical perspective. I think I just took advantage of the fact that I was just living in flux for about a year, and I was trying to make the best of it.

It is structured that way because it was first produced as a podcast, and I think podcast episodes… I guess that doesn’t make sense, because in books, you’d also want to have them captivated to read the next chapter. But it feels especially true for audio, for some reason, in my opinion.

Joanna: What other tips would you give for people in terms of writing? You mentioned there the text message into dialogue. Because you’ve never written a memoir, right? This is your first memoir, but you’ve written a lot of other books.

What are the other things that you’ve brought from your fiction writing experience?

Kory: I had experimented with memoir when I was getting my MFA, because they do want you to play with other genres, and literary fiction I just found difficult for some reason, even though it’s not really that much different than the fiction I write, but because I couldn’t whip out a superpower for someone, for some reason, it caused a blockage.

So I played with memoir instead. And so I had written some memoir-type stories. But you’re right, I had never tackled a memoir for publication before.

As far as tips about how to do it, I would say, absolutely, be very honest, but that you are also allowed to lie. What I mean by that is, you’re allowed to lie in the sense of what I was just saying about the dialogue; if it doesn’t work exactly as it said, you can keep the meaning of the conversation, or you can keep the meaning or the significance of what happened, but reword it in a way that is better for the flow of your story, for the cohesion of your story, for the integrity of your story.

Also, I had a few little lies in there about people’s names. For example, there are some people who are still living, that I didn’t want to drag them into such a brazen display of family trauma, if they didn’t want to be known for that, so I used different names for them.

Be very honest in how you felt what the experience was, but on a technical scale, you are allowed to, I think, change some details, either to improve the story or to protect other people. I think that that’s perfectly allowed. I don’t think that there’s anything disingenuous about that.

I would also recommend that you…and this might go back to your question about, how do you write about it without just turning it into therapy on the page, is that when you connect with your feelings, do it from a place of curiosity and acceptance, if you can.

For example, I love the Buddhist nun, Pema Chödrön. I read a lot of her books. I listened to a lot of her audio tapes. She’s helped me a lot with contextualizing my own life. And she talks a lot about this idea of working with difficult emotions from a place of curiosity.

There was a exercise that her teacher gave her that was like, ‘Okay, so you’re feeling sad, right? Or the emotion you’re connecting with right now is sadness. What does sadness feel like in the body? What color would sadness be if sadness was a color, if it was an art style? What art style would sadness be? If it was an actress, what actress would sadness be?’

So you start to think about your emotions in a way that it puts you in this position of being curious about them. And so you think about it, you don’t just get pounded by the waves of sadness. You’re looking at it from this other position, and you’re also, at the same time, though, maintaining that intimacy with the emotion.

You’re not stepping away from it. It’s not like you’re trying to escape your sadness. You’re actually really looking at it. It’s like, well, if it was an art style, what art style would it be? If it was a shape, what shape would it be? You get really up close and personal.

And then also acceptance, because I think when we have a hard time with emotion, it’s because we’re struggling against whatever we’re experiencing. So it’s never really that sadness itself, for example, or grief is the problem.

The fact that you’re grieving is not a problem. It’s the fact that you tell yourself things like, ‘I shouldn’t be feeling this way.’ Or ‘I shouldn’t be grieving,’ or ‘I have so much to do. I don’t have time for this,’ or ‘So and so lost their person, and they didn’t completely fall apart, and I must be doing it wrong, or I must be weaker.’

It’s all the things that we add to our perception of our experience and, in a way, reject it that I think makes it so much harder for ourselves.

If you can come at your emotions and your experiences from this place of curiosity and acceptance, I think it would be a lot easier for you personally, just living, but also in crafting your story and bringing to the page what you need to tell the story that you need to tell.

My last tip would just be, be incredibly gentle with yourself.

And that’s with the acceptance. This is not something you need to bulldoze through, necessarily. A lot of indie writers, we’re on schedules, like, ‘We have to put out 10 books a year. And if I don’t put out 10 books a year, I won’t be as successful as X, Y, or Z.’

But a memoir or a story like this, that’s probably not the time to give yourself a really intense deadline. If it takes you longer to write your memoir, that’s okay. It requires a level of emotional and mental commitment that necessarily not all stories do.

So don’t just ram yourself through this gauntlet of a deadline. I don’t think it will make your story any better, nor will it necessarily help you in any way. So take your time and be gentle.

Joanna: I think that’s right. You often hear fiction writers, ‘I’m going to write that fight scene. It’d be so much fun. I’m going to blow this up and kill that character.’ And I haven’t heard any memoir writers talk about memoir writing as fun. I think it’s very satisfying, and you feel very proud of your work, but I think no one would describe it as fun. Obviously, because of your situation, it was not a fun memoir.

Kory: No, I would agree with your assessment. I was satisfied with the job that I had done. I do feel that I told the story the best that I could and that I was very honest, which was what was important to me.

Because that was a personal achievement for me, just because the tendency, I think, for people who come out of traumatic backgrounds and who kind of shore themselves up, make themselves tough, is that they’re not necessarily good at showing their soft bits, their vulnerabilities.

In my fiction, I reread a lot of my fiction lately, and my different experiences, my difficult childhood, it’s all there. I can see it now. I thought that I was being really secretive, like nothing was getting on the page. But it’s all on the page in any of the books I write.

But it was easy to tell stories about someone else like it was someone else’s trauma, someone else’s difficult experience, not mine.

Being open and vulnerable is really hard. Especially if you come from a place where that could really be exploited or dangerous in certain company. It’s hard to show those parts of yourself. So you kind of have to really have a level of self-confidence that, ‘I’m going to put this out there.’

Even if someone says something horrible to me about it, I still needed to tell the story. And the story was still important. I was proud of myself that I was able to get past sort of these hang-ups that I had about, like, ‘Well, I don’t want them to know it was so hard. I want them to think I’m a badass who has no problems in life.’

There was a level of reasoning with myself there that took some… It’s mental work. It’s like you have to really sit down and negotiate with yourself.

Joanna: Definitely. I do want to circle back, you used the word ‘lie’ earlier, which I think the word ‘lie’ is…and the examples you gave, I don’t think were lies, they were changing people’s names. They were keeping the meaning of a text message into dialogue.

But I think this is really interesting with memoir, and I’m not saying that you were lying, but you do write about your mother’s history. And your mother is obviously not around to fact check the past.

Therefore, how do we research the background of someone we’re so personally connected with, but still can’t fact check?

How were you sure of the things you wrote about your mother’s life when you couldn’t mine her brain for the information? How do you make sure that is true and the meaning is there?

Kory: It’s a good question. In truth, even if my mother had been alive, because she was so mentally unwell, she wouldn’t have been a good source of factual information anyway.

My mother, especially toward the end of her life, she was having memory loss problems, so she wouldn’t have been a good source anyway. And that might be the case for a lot of memoir people, like maybe if someone wants to write about their parents who have dementia or something, it might be very true that you don’t have a person to fact check you, even the person you’re writing about.

In my mom’s case, because of her schizoaffective disorder, it wouldn’t have been helpful for me to check with her. There were two people who are still alive who knew her really well in her past. Both of them had been romantic interests of her. One, they had been married briefly, and another, they had just been together for a really long time when I was a child.

And so I did ask them a lot of questions, and I uncovered some pretty shocking secrets about my family. I trust that there is perception, because they did give me information I didn’t have, but a way around keeping the integrity of your story, even if you don’t have necessarily all the ‘facts,’ is focusing on your experience.

The story is the investigation of my mother’s murder. But it’s more about what it was like for me growing up with a mentally ill mother who was struggling with drug addiction. She was diagnosed with manic depression when I was young.

Manic depression…now we call it bipolar. But back then, it was manic depression. She would have these episodes. I didn’t really understand why she was so sick and what was happening with her and why she would have these complete personality and emotional shifts, like in the blink of an eye.

By focusing on what that was like for me, in those moments, I’m still being very honest; there’s nothing untrue about what I was talking about these experiences in each moment. But maybe I didn’t have the fact of why she was so ill, necessarily.

I do feel that I uncovered that now by interviewing the people that knew her in the past. I found some source information. I call it the Detonation Event, the reason why I think that she was so mentally unwell. I was able to get that by investigating people that knew her.

By sticking more closely to my experience, I think you’re able to remain true and honest, even if you don’t have that person, because it’s very possible, especially if you were an older person, maybe, and a lot of people have died or the person you’re writing about has dementia, maybe you don’t have that to check with. I think if you just stick to your experience, you can still tell a very honest story that’s very truthful.

Joanna: I agree with you. I know that’s something difficult, although, to be honest, I can’t remember so much about my own life, let alone anyone else’s!

Kory: Well, I guess we could say that’s a good thing about trauma, is that it blazes your experiences onto the retina of your mind. I retained everything. I have kept a lot of journals and stuff. So it had helped. But you’ve talked about how you write journals, and you go back and you’re like, ‘I don’t know her. I don’t know who she is.’

Joanna: Exactly. I find it fascinating that we can read something that we wrote, and we don’t feel we are that person anymore. I think that’s what gives me pause in terms of trying to think about what another person would have felt or considered when that person is different as well now.

I think this is why memoir is so hard, because history is always an ever moving river, and things change and people change. We have to write about different points in time. And, as you say, you have an A story, which is the investigation, and then your B story is your experiences in the past and your mother’s history and things like that. So I think it’s a deceptively difficult genre to write.

I wanted to get into the podcast aspect. You mention that you wrote this as a podcast first.

Why write it as a podcast first? And then why change the format into a book?

Kory: Another good question. I have talked about and explored trauma adjacently in all of my novels. For example, in my ‘Shadows in the Water’ series, the main character, Lou Thorne, she’s a sort of vigilante-type character who hunts down and kills this mafia family because they had killed her father, who was a DEA agent.

And so she has this traumatic moment that keeps coming back up. If you’ve ever read…oh, gosh, Donald Maass did ‘Writing the Breakout Novel.’ Did you ever do that?

Joanna: Yes.

Kory: It comes with a workbook. I know you like workbooks. But he talks about high points. And so one of her high points that she revisits a moment that’s blasted into her mind is where she’s on the back patio talking to her father.

He wants to get her some help because she has this ability to travel by water and shadows. But she’s terrified of it because she can’t control it. So the water and the darkness sort of just swell her up at random, and it’s terrifying for her.

He’s telling her this, and he’s trying to comfort her that she’ll be okay. And then these bad guys show up, bust into the house. You see the light go off in the bedroom, know the mom’s been shot. And then here’s the guy pointing the gun at her dad, and he picks her up and throws her into the pool, knowing that it would save her. That’s her traumatic experience.

Everything that she does going forward is to process that experience. So I understood kind of intimately, from my fiction, that this is what happens. Something happens, and then you do things to process what happens to you.

But I had never talked about my trauma, like, ‘Here is Kory, and this is what happened to her.’ I was always like, ‘This is what happened to somebody else.’ Like, ‘It’s not me.’ It was always me. But it was like, ‘It’s not me, it’s someone else.’

With the podcast, I felt like, ‘Okay, if it’s really going to be me, then I’m going to do it. I’m going to do it with my voice.’ It was almost a commitment to fully step into the light to do this.

I was like, ‘Okay, I’m going to tell the story with my own voice. You’re going to hear my voice say what happened. Everything that happened to me, happened to my mother, happened to my family. It isn’t fiction. It isn’t fantasy.’

I think that the element of using my voice is really important.

And the opposite of that being, it’s fiction, it’s written down, it’s about someone else. So it felt like a very strong shift to stepping into this position of, ‘I’m really going to tell my story. And I’m going to tell it like this so that you can hear me.’

It would be like telling a friend, almost, like, ‘I’m going to tell you this thing that happened to me. I’m going to share it with you.’ I think it added to the intimacy and the honesty of the story, like, telling it with my own voice.

Joanna: Yes, and true crime podcasts are one of the most popular genres of podcasts. And so it seems totally horrible to ask you about marketing.

Kory: No, I really can separate them in my brain. Don’t feel bad. I really am Kory with the publishing hat, Kory with the writing hat. I can do it all. So, absolutely, ask me whatever you want. I’ll just put the other Kory away.

Joanna: Well, so how has having a podcast of the book…has that helped the book sell? Have you done an audiobook version as well? Because, obviously, there’s different platforms for these things. And how has the marketing gone for it?

Has having a podcast of the book helped the book sell?

Kory: It’s interesting, because the book hasn’t come out. Well, actually, I think when this interview goes out, it will have just published. I can’t say that I’ve seen anything happen with book sales, because the book doesn’t exist in physical form yet, but I did want to release a book because not everyone who listens to podcasts read books.

I have a friend, for example, she has no physical time between her nursing school and her two kids in her life to sit down and read a physical book. But she loves stories. So she does podcasts and audiobooks. So I’m thinking of someone like her for the audio-only stuff.

And then there are people who they can’t imagine listening to stuff. They want to hold a book. So I have a book for them. That’s why I have all the different formats.

As for marketing them, I really do think it comes down to who you’re trying to reach. I have seen the people who listen to my podcast go and buy my fiction, because the fiction does exist at present. And so they read that, and they’re like, ‘Oh, this is a really interesting mystery. I like Kory’s style. I like how she unfolds it. That’s very cliffhangery. It pulls me right through. I blasted through it.’

And then they pick up Shadows in the Water, for example, that also has these crime elements. And they’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, I can see the same style. I really enjoyed that.’

There is some crossover between the memoir and my fiction, which I did not expect, at all, because just getting your readers to go from one genre to another or one series to another is really hard.

For example, I just published three sci-fi books, and not everyone’s jumping ship from the Shadows to the City books, which are set 500 years in the future in a post-climate-change world, but it’s also a mystery. It’s a police procedural, essentially, with these two characters.

So it’s very interesting, the hang-ups that people get about trying different things. I don’t know, I guess I understand it, though, also, because you only have so many hours in the day. You need to be very choosy about the entertainment that you use for that.

I do find that another marketing tip is that I created a newsletter sequence for the podcast people. So, for example, I had a few extra things that I had shared on my Patreon, some side audio stories that were adjacent to the ones that I had put on the podcast about my mom’s story. I put those in a newsletter sequence so when people listen to the podcast, they get the pitch to sign up for my newsletter, and they did do that, and they were interested in that.

I’m also putting the autopsy report on there, which sounds macabre, but some people like the mystery aspects and they want to see.

They’re like, ‘Yes, give me the files, give me the files. Give me the family photos. I want all the details.’ I put that up there in case they want to see it, they want more of the information.

I did get newsletter signups that way as well, because it was an audio offering, so they were listening to audio, and what they get is audio. They’re freebies, which I think was a good choice, as opposed to sometimes when we offer audio, but we’re like, ‘Okay, here’s a book,’ but maybe they don’t have time to read a book. Maybe that’s the reason why they chose a podcast to listen to, for example, while they’re washing the dishes, or the car, or whatever they’ve got to do with their life.

Joanna: I guess the question I have here is, so you did the podcast first, then you took, obviously, the transcript or the words from the podcast that you’d obviously read out, so they were written down anyway. Did you edit that again? And then are you going to turn that into an audiobook as a product?

The main difference, obviously, is a podcast is free, and the audiobook, you can sell. And also people listen on different platforms. So you’re going to get discoverability on Audible audiobook platforms that you get a different discoverability on podcasts.

How will those two products differ between the podcast and the audiobook?

Kory: I was on the fence about it. And you just made a really good pitch for why I should put it out. So thank you for making that decision for me.

Joanna: Oh, good.

Kory: I had been thinking about the things that you just mentioned. You’re right, they are different platforms. Someone who is on Audible, for example, aren’t necessarily listening to Apple podcasts, or there’s not necessarily any overlap in those markets.

I have thought about what I would do differently. I would need to rerecord it, because the podcast files that I uploaded, they have all the music and stuff put on. Because I made my own music for the show using this steel tongue drum that my wife had given me as an anniversary gift. So it’s got this really haunting, beautiful sound.

It’s interesting, but I don’t know that it would work in an audiobook because they have the silence between the chapters, and you get to upload it, and Audible has to prove it. And maybe they’d be like, ‘What is this weird music here in the beginning of each chapter?’ So I would need to redo it. And yes, I did edit it.

The whole process was, I wrote the episode, I got in the booth with the episode, realized I couldn’t say something while I was recording the episode, rewrote the sentence, and then said it again. That was happening. So there’s also edits that were happening as I was recording each episode.

And then I edited it again, gave it to my editor, and he edited it for me again, and then it went to the proofreader. So it is slightly different than it would have been as a podcast, and I believe audiobooks, they need to match pretty closely.

Joanna: That’s only on Amazon and Whispersync.

Kory: Yes, Whispersync.

Joanna: But I, personally, I don’t even bother about that anymore. I just do what I do.

Kory: Who cares? We have better things to do with our life. Yes, so I mean, I would need to do that. But I think I would have to rerecord it if I wanted to do it.

I do like the idea of having it free, having the audio aspect free. And maybe that would also have some visibility, because you can go to my website, and it’s set up as a player. You can just play through the episode. So you don’t necessarily have to be on podcasts, for example.

There are some people who don’t even know how to get on to a podcast app. I’ve run into that where they’re like, ‘I do want to listen to your show, but what do I do?’ t was surprising to me that a lot of people still don’t know what they are and how to use them. So for someone like that, the player would be useful.

Joanna: This is definitely something I think about. For example, I have some short stories, which are on YouTube audio for free. And you can get from my Payhip for free. I also sell them on the various audio apps.

I think we do this for ebooks. We give away ebooks for free as a sign up. And we also sell them. So I don’t think there’s anything wrong in having the same material available for free as a podcast, but also for sale on the audio apps and as a book.

We need to put things out there for people in the way that they want to consume them and not just assume that they’d rather have it for free.

Kory: That’s absolutely true. I was thinking at first not having something behind a paywall was making it more accessible. But you’re right, there might be a reason, another accessibility reason why someone needs it in a certain format that I’m not thinking of, so good point.

Joanna: Yes, or even just on the platform. I buy audiobooks direct from authors, but I also have the Audible app, and it recommends things in the same way that Amazon always does. And so if it recommends something, then I’ll put it on my wish list and discover it that way.

I think that’s what I’m trying to say is that there are lots of ways that people will discover audio that might not be how you do it. I guess it’s good we’ve had this discussion, because I have also thought about this. I haven’t even written my memoir yet, and I’m thinking about this too.

Kory: You should absolutely write your memoir. Is it the travel memoir that you’ve mentioned before?

Joanna: Yes, it’s going to happen. It’s totally going to happen.

Kory: Just get in there, feel your feelings, be accepting and curious. I’m sure we will be super excited to read it.

Joanna: Right. Well, we could talk about this forever, but we are out of time.

Where can people find you and your books online?

Kory: The easiest way to find me and all that I do, you could just go to whokilledmymother.com, and that has links to the different kinds of books and series that are right. So everything’s on there.

Or you could pick up ‘Shadows in the Water’ or ‘Dying for a Living,’ because they’re both free at the moment. So enjoy.

Joanna: Right. Well, thank you so much for your time, Kory. That was great.

Kory: Thank you so much for having me.

The post Who Killed My Mother? Writing And Podcasting True Crime Memoir With Kory Shrum first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn