How can you write through self-doubt? How can you break through Resistance to write and market your work? How do you decide which book to write next?

Steven Pressfield talks about being a warrior of the blank page, how he deals with Resistance around writing and marketing, as well as self-doubt and other aspects of mindset that we all face on the writer’s journey.

In the introduction, the first traditional publisher produces an AI-narrated audiobook with Google Play’s beta program [Publishing Perspectives]; Deep fake Tom Cruise [The Guardian]; Hyper-realistic, emotionally expressive and controllable artificial voices [Venture Beat]; Spotify rolls out to 80 new markets and 36 languages [Spotify PR]; Clubhouse for Writers.

Plus, I talk about lessons learned on the Wish I’d Known Then Podcast, and about literary prizes and competitions on the Ask ALLi Podcast; and if you love horror/dark fiction, you can be in to win 6 signed paperbacks in this limited-time promo (8-15 March)

This podcast episode is sponsored by Publisher Rocket, super-useful software that will help you choose the right categories and keywords for your book. It includes Competitor Analysis so you can see what categories other books are in, Keyword and Category search tools, and keyword help for Amazon Ads. Check it out now at www.TheCreativePenn.com/rocket

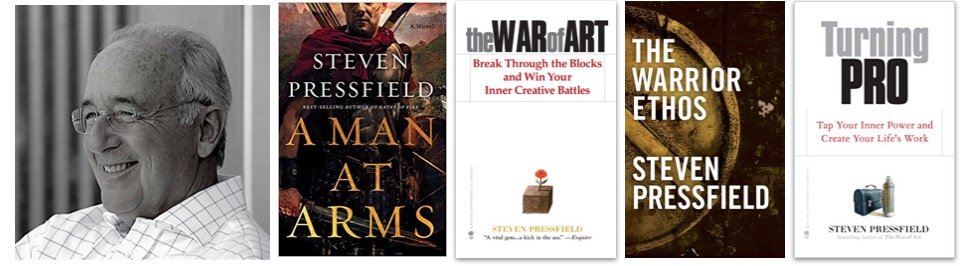

Steven Pressfield is the international bestselling author of non-fiction books including The War of Art, Turning Pro, and The Lion’s Gate, as well as novels including The Legend of Bagger Vance, Gates of Fire, and Killing Rommel. His latest book is historical thriller, A Man At Arms.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and full transcript below.

Show Notes

- Resistance to marketing and how you have to overcome the feeling that you are a ‘bad person’ to want to market your books

- The virtues of the warrior — and how to be a warrior of the blank page

- Researching historical novels … and how much to make up

- What is the story really about?

- Self-doubt and the mindset of the long-term creative

- Why Steve is still blogging and making videos as part of his book marketing. His latest series is on The Warrior Archetype

You can find Steven Pressfield at StevenPressfield.com and on Twitter @SPressfield

Transcript of interview with Steven Pressfield

Joanna Penn: Welcome back to the show, Steve.

Steven Pressfield: It’s great to be back, Joanna. It’s great to be on ‘The Creative Penn.’ This is one of my favorite podcasts of all. It’s always great to be with you.

Joanna Penn: You are back for the fourth time so you’re definitely one of our most returning guests. We’re going to get into your new book soon, but I wanted to start with the question. We’re in a pandemic still as we record this February, 2021, many authors are struggling to write.

How have you been staying creative during the pandemic?

Steven Pressfield: It’s a great question. First of all, I found that the writer’s life, or at least my writer’s life is not that different from the lockdown life. Basically, I’m at home, in a room, staring at a screen.

I go out for a coffee once in a while and I come back. But I would say like the first half, since March to wherever, it really didn’t affect me at all except, maybe working longer hours. But then I had a switch, and this may be of even more interest to our listeners. I’m going to give you, kind of, a long answer here, Joanna.

I’ve never been a great marketer of my own stuff, a great promoter of my own stuff. I go on your podcast and that’s about it. But for my new book coming up, A Man at Arms, I decided I’m going all out this time. I just can’t stand to have another book of mine come out and just vanish without a trace.

So for, maybe, the last six months, I’ve been just about doing nothing except working on promoting the book, one way or another. So that’s been my creative nemesis.

I find that I have tremendous Resistance, with a capital R, against promoting my own stuff. I feel like I’m a bad guy, I’m forcing myself, I’m inflicting myself on people, that kind of thing. But I know I shouldn’t think that way and I know that that’s a real amateur way of thinking.

In any event, that’s what I’ve been doing, really, for like the last six months with my girlfriend Diana. We’ve been working together and we’ve been just working on that, on promotion.

Joanna Penn: Wow, it’s so interesting you say that about resistance around marketing, because of course in The War of Art, your great book for writers, which I’m sure everyone’s read, but you talk about resistance in there, and I don’t think I’ve really heard you talk about resistance to marketing before.

How did you get over that? Like you said, it’s an amateur way of thinking.

How did you push through your Resistance to marketing to do all the videos you’ve been doing?

Steven Pressfield: I’m still in the throes of pushing through it and I haven’t mastered this by any means. I really have to flog myself each morning to do it. But there’s a couple things, one is, my previous, the most recent book called Thirty-six Righteous Men, which was a real killer to write. It took me like three years. It was really, really hard.

I didn’t do any promotion. It came out and it just died. And I think it died, not so much because it’s not a good book, but just, nobody knew about it. And so I just said to myself, like, ‘My career is over if I can’t solve this.’

Because, these days, if you go with mainstream publishers, they really don’t do anything for you or they only do the very expected stuff, and that just doesn’t work anymore. So I really felt like it was like almost a career question for me, I just had to do this. I had to master this or at least make a shot at it somehow.

Do you know who Ryan Holiday is?

Joanna Penn: Yes, he’s been on the show a couple of times.

Steven Pressfield: Oh, yes. Ryan Holiday is everywhere. I’m friendly with him and he lives in Texas, I live in California. So I called him up and I said, ‘Can I come visit you and give me a few hours and just teach me what you do.’ And so he did.

We spent a day together in Texas. And a lot of what he told me, I was taking notes feverishly and he was sending me stuff on email. I also made a new friend, a guy named Jack Carr who is a thriller writer. You may have heard of him, former Navy Seal sniper. And he, like Ryan, he is like a great marketer of his own stuff.

I watched him, and I saw how, for like two months at a time, he was doing nothing but marketing his most recent books. So they’ve been role models for me, and helping me get over the idea that I’m a bad person if I do this.

And I realized that I still hate to do it, I still feel bad about it, but I realized that I just have to. I don’t even know if this is going to work. I’ve been blitzing this thing now for months and I have no idea if it’s going to work. I have to have the attitude, if it doesn’t work, so be it.

But I think by the end of this, I’ll be sold on this as a way to do it. When all is said and done, Joanna, I will have spent as much time on marketing as I did writing a book, for whatever that’s worth. And I think I’m also lucky in that I’ve already got a bunch of books out there and people have heard of me and I do have a little bit of a fan base. So I would imagine it’s really, really hard if you’re starting from scratch.

Joanna Penn: Marketing is definitely tough and I’m always encouraged by what you share. You always share very honestly and openly. And I think you’ve always done this though, your almost memoir, The Knowledge.

You talk there about overcoming the problems and getting to the typewriter. And so you’ve overcome these challenges over and over again in your writing career, and you’re still showing us that.

I did want to ask you about that because overcoming resistance is also a matter of discipline. Like you said, ‘I flog myself to do this in the morning.’ And sometimes it feels like that going to the writing page as well.

Let’s get into A Man at Arms, because you use a lot of warrior metaphor, a lot of discipline metaphor, a lot of strength, and you’ve got a video series on the Warrior Archetype and it underlies The War of Art.

Tell us a bit about how your own military background underlies the books you write and how much of you is in Telamon, the main character in A Man at Arms?

Steven Pressfield: I didn’t have a long military career. I was a reservist so I was six months of active duty and then five-and-a-half years in the reserves. But it did really stick with me. But I think that in many ways, so the discipline that I learned came from failing so much as a young writer, and running away from doing the work, and then going down terrible rabbit holes in my life.

Having things just go really bad in my life, and finally realizing that the discipline of writing was what would save my life, would kind of keep me on the right track. And if I didn’t do it, and I know, you know all about this, Joanna. It’s really what you talk about over and over.

I’m not a very nice person to be around if I’m not working, and I’m not fun for myself to be around. Whereas if I am working, then I am as much fun as I could possibly be.

So I think the discipline, a lot of the military, I think of myself, not to make this sound too over the top or anything, but I do think of myself as like a warrior of the page, of the blank page. And I bring the virtues of a warrior, I think are applicable also to the virtues of a writer or an artist, for instance, courage, for one thing, patience, a really big one, selflessness, and another big one is the willing embracing of adversity.

That’s kind of a warrior type of thing. And I think it’s absolutely, for a writer or an artist… we all know what the slog, what it is.

Another thing, to go on a little sidetrack here, another metaphor that I use sometimes other than warrior is a mother. If you think about a mother, there’s nobody braver or tougher than a mother, particularly with a baby, with a newborn.

A mother will run into a burning building to save her baby. She’ll lift a car with two hands to save her baby. And I think that we, as artists, we are pregnant with our work. And like a mother, we’re trying to bring in new life to the world. And we set our own ego aside and our own needs aside just like a mother to protect this new life that we’re trying to bring forth.

So that’s another kind of metaphor or model that I use in my own mind as I’m trying to overcome my own resistance, and self-sabotage, and procrastination, and all that kind of stuff.

Joanna Penn: I think sometimes we need these metaphors to keep us going and overcome the challenge. The warrior doesn’t always win as well. Sometimes you’re on the losing side.

Steven Pressfield: Right, right, right.

Joanna Penn: So that can help when your book doesn’t go so well.

I want you to come back to the character of Telamon of Arcadia. He is the only returning character in your books. What is it about this character that you were like, ‘You have to go back?’

What makes this character stand out for you?

Steven Pressfield: While I’m talking about flogging my new book, which is what I’m going to do right now as opposed to flogging myself in the morning to get done. But the new book is called A Man at Arms, and I have this one recurring character, only one recurring character in all my books, Telamon of Arcadia is his name.

He is sort of like a gunslinger of the ancient world. He’s like a one-man killing machine of the ancient world, instead of using a Clint Eastwood man-with-no-name character. What’s fascinating to me about this character, he’s definitely an alter ego for me, is that he just sort of materialized on the page for me. He first appeared in a book of mine called Tides of War. And then he came back in another one called Virtues of War, 100 years apart and he hadn’t aged a day.

I had not planned the character in either one of these books, he just sort of appeared, full blown. And what was interesting to me was that he had a philosophy. He wasn’t just a guy that was out there slogging through the mud or anything, he was like a thinker and he definitely had a philosophy. It was a dark philosophy and it came out fully formed, and I didn’t even know what it was.

It wasn’t like I sat down and said, ‘I’m going to create this character and here’s what he thinks, A, B, C, D.’ And it was a fascinating philosophy to me too, so I wanted to find out more about it. Over the years, readers have written in to me and said, ‘When are you going to bring back this character Telamon? We want a book only about him.’

And I thought, ‘I want to do that too.’ For years I tried to come up with a story. You know how you’re looking for a story and you do an outline, you do another outline, it doesn’t work and it doesn’t catch fire. And finally about three years ago, I got a story that I liked. I was excited about it and I’m still excited about it because it allowed me to explore this character and find out what his philosophy was and how it was going to change through this story. I wanted to know what happens to this guy.

Joanna Penn: Would you say he’s an archetype? Because again, you talk about the warrior archetype, the warrior ethos? Is he your archetypal warrior? And you say he is your alter ego in a way.

Does he represent a Jungian psychology archetype of a warrior?

Steven Pressfield: I think he does, Joanna. I think he does. There are lots of different warrior archetypes, there are lots of different styles.

Alexander the Great would be a certain kind of a warrior, or Leonidas of Sparta would be one. But Telamon is definitely a warrior archetype that I can relate to in that he has taken this identity of a warrior as far as it can go, nobody can beat him, he can’t seem to die, he’s a whatever.

But he is tormented by this and he is searching for whatever comes next. And I feel like I’m in that position too in a way. As a writer, I’ve got it down in terms of my own self-discipline. I can kind of do it. Not completely but pretty much. And I’m searching for what am I missing here, what’s the next thing?

Is there an element that I’m leaving out? I think the element is actually love when it all comes down to it, but I’m probably getting ahead of myself here. But, yeah, he’s like, he is an alter ego for me, this character of Telamon.

Joanna Penn: Obviously, this is an ancient-world setting, it’s set in 55 A.D., not long after, obviously, the crucifixion of Jesus. And you’ve written about Judaism before in several of your books.

How did you research this era and how do you balance the historical truth with what some people might consider religion or faith?

Steven Pressfield: Ah, it’s another great question. Here’s another thing, Joanna, of course sort of as a sidebar to that question. And I know you know this. When you start on a book, a lot of times, you don’t know right away where it’s going to be set or what the time period is. It just pops out.

For me, the date of 55 A.D., 20 years after the crucifixion or there about, I just sort of knew that that was when it wanted to be set. I don’t know why. And as I got into it, it became really clear to me that this story was in the aftermath of the crucifixion.

It was sort of like, what’s going to happen? We’ve seen what happened with Jesus, but is this new religion just going to peter out? Is it just going to go away? Is Rome going to crush it as an empire? What’s going to happen here? I hadn’t even really thought about that until I was in that moment. I put Telamon in that moment.

I’ve given away some of the story, I might as well, you know? The gist of the story is, there’s a letter sent by the apostle Paul to Corinth in Greece to the community, the Christian community in Corinth. The letter that would become the book in the Bible, 1 Corinthians.

It’s the letter that has, ‘When I was a child, I spake as a child, I thought as a child,’ etc., etc. And the thing of, ‘Faith, hope, and charity, and the greatest of these…’ It’s got a lot of great quotes that we remember in it. I wanted these bad guys to try to stop this letter and that Telamon, my gunslinger character, would be hired to stop this letter, and then things would happen from there.

But getting back to faith. I know I’m blathering on here, Joanna, but I will.

Joanna Penn: I’m enjoying it!

Steven Pressfield: When a character, any character in any book or movie, if it’s Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, if it’s any character, when they change, any hero, they have to change or there’s no story. And when they change, that change almost always takes place on the soul level, on the spiritual level.

If we write a story and it only takes place on the behavioral level, the change or, the superficial level, then the readers, it doesn’t resonate, it doesn’t work.

It has to happen. It’s almost like any story, when it comes down to the climax, comes down to some concept of faith. It might not be something that you would name as religious. But the ending of Casablanca, just as a classic example that we all know, where Humphrey Bogart puts Ingrid Bergman on the plane to Lisbon, and he gives her up for the greater good, for the greater cause of the resistance of the Nazis.

That’s a change that’s happening for him on the soul level. He might not cite religion or anything like that. In fact, I’m sure he wouldn’t. But the reason that change is so powerful is because it happened on that level. So that was what I was trying to get to in this book, A Man at Arms and have my character Telamon change on the soul level and coincided with faith in this case.

Joanna Penn: It goes really deep on the theme just returning to the research. I know a lot of people love writing historical fiction and you’ve written a lot of historical fiction as well. Obviously we’re in COVID times, you’re not going back, but I know you’ve been to Israel and done a lot of research there before.

How are you researching that period of history? Are you reading a lot of nonfiction or how do you research?

Steven Pressfield: I’m going to say something that maybe will surprise you, or maybe will be liberating to our listeners. A lot of the stuff in my books that seems like its absolute research is, well, I’m just making it up.

Well, let me go back to an earlier book of mine to Gates of Fire that was about the ancient Spartans. And in researching the ancient Spartans, there’s very little about them. We only have like 24 words that are written by an actual Spartan. The rest is all from various Athenians and stuff like that.

So one of the things I did in writing Gates of Fire was, I would come up with a term in English, let’s say for a type of military exercise, and I had a friend, a Greek friend, Dr. Hippocrates Konzos. I would send him this term in English and I would say, ‘Give me the Greek word for this,’ and he would.

And then I would kind of put that in the story. And, basically, I’m making it up. But when you read it, you go, ‘Wow, that is so real.’ But again, I had to because there is no real research for that era.

In your country in the UK, let’s say you wanted to write about Queen Boudica, if I’m pronouncing that right, from wherever that was, from 1st-century AD, fighting the Romans. I’ve looked it up, there’s very little about it. If you’re going to write about it, you’re basically going to write Game of Thrones. You’re going to have to invent whatever it is.

So I did a lot of research in Israel. I was in Israel for nine weeks. I went over the ground, I talked to millions of people or lots of people, and I imbibed a lot of stuff there. But for instance, A Man at Arms, a lot of it takes place in the Sinai desert. And I knew a fair amount about that from talking with Israeli-tank commanders and infantry men and stuff who were there during the Six-Day War.

But I wasn’t allowed to go in the Sinai Desert because that was Egypt, it was a border you couldn’t cross. So in the story, A Man at Arms, one of the characters is a witch, is a sorceress. And one of the things she does is, she gathers medicinal plants from the desert and makes me teas and these things that help keep people awake, and help heal wounds, and stuff like that.

I looked up as much of that stuff as I could, but then I just invented names. I just invented the name of a plant and that it did such and such a thing, had such and such an effect. I shouldn’t give this away, but if you read it, you think, ‘Holy cow, this guy really studied. He knows the whole geography, botany of the Sinai Desert.’ But I really don’t, I just made up a lot of it up.

Joanna Penn: I love that. I actually think that is very liberating. I recently went on pilgrimage to Canterbury and I’m writing Day of the Martyr and I have the Thomas Becket Murder. And that’s 850 years ago. And, of course, there are accounts but they’re very biased.

So even if there are accounts, so for example, Paul’s letter to the Corinthians. Obviously, we can read that, but then the church, obviously, got rid of anything that criticized Christianity later on and got rid of the Gnostic Gospels and all that. So much of even if we think we’re researching, we’re researching from a biased point of view.

So almost, by making it up, you’re adding a bit of balance, I think, to the bias.

Steven Pressfield: That’s how I look at it. Definitely, Joanna. Because it’s like if you’re researching Alexander the Great, there’s no document that was written less than 400 years after his death. And just like you say, the bias, either they hated Alexander and they painted him as, really, a bad guy, or they loved him and they cut out all the bad stuff about him.

So the historical fiction writer, it’s our job, I think, to enter that unknown territory via the imagination, and just ask ourselves, ‘What would it really have been like?’ A lot of times I find when I’m doing research, I’m reading between the lines. I’m trying to say, ‘Yeah, this guy is saying this,’ but what was really going on there?

And I think, when you do that, those are the scenes and the elements that readers really respond to and really feel like, ‘Oh, that really brought me back there.’ You have to be brave and be willing to state things that you don’t know for sure.

Joanna Penn: I think you’re really also talking about subtext where you might be saying one thing but you actually mean something else. And you’ve talked about the levels that a reader will want to connect with on a soul level. So it’s not like Telamon had a sword fight. Yeah, that’s great, but also Telamon is experiencing something on a deeper level.

You mentioned also that you do an outline and then you work from that.

When you’re planning your outline, are you thinking about the conflict on the higher level and the conflict on the lower level at that early stage, or is that the type of thing that emerges as you write?

Steven Pressfield: That’s a great question, Joanna. I think it’s a little bit of both. A lot of times, I think I’ve had this experience with my great editor Shawn Coyne numerous times where I’ll finish a book, completely, I’ll write 10 drafts and give it to him, and then he’ll tell me what it’s about.

I don’t know. He’ll explain to me the deeper story. Almost always he’ll do that and I’ll go, ‘Wow, did I really write that?’ And then I’ll go over it again with that in mind. But having had that experience with him a bunch of times, I’ve learned to jump ahead of him a little bit and now I ask myself.

I was reading a story about Steve Jobs, the guy who founded Apple? And, supposedly, he used to go around the workplace and stop at people’s offices and cubicles and he’d ask them, ‘What business are we in?’ And then he would ask them, ‘What business are we really in?’

What I took from that as a writer is, it’s like asking, ‘What is this story about?’ And then, ‘What is it really about?’ And that ‘Really about’ is the deep, deep level, is the soul level. And I will, at the start of a story, like with the character of Telamon in this story, I definitely did an outline that I called ‘The Understory.’

I sort of started with, where is he at, at the start of the story and where do I want him to be on the soul level at the end of the story? And then I would go back and look at the various beats where he would change. Does he change slightly here in act one, then he changes a little more at this scene?

I really wanted to make it absolutely clear in my mind, and then there would be a big moment when he really changed. I highly recommend that to myself, going forward in anything else I do, is asking the question, ‘What is it about?’ And then, ‘What is it really about?’

Joanna Penn: I was just thinking then about the question you said, ‘What business are we in? What business are we really in?’ And I want to come back to you on that with that question about us as writers. Because I feel like on the one level we want to please ourselves when we write but that’s not the business we’re in. The business is not pleasing ourselves.

Steven Pressfield: Before I even plunge into that, let me just talk about the UK for a second. You could very much say, ‘What is Brexit about?’ And then say, ‘What is it really about?’

I don’t know what the answer to that is. On a really deep level, it’s some sort of reclaiming of the identity that goes back to when you guys used to paint your faces blue and fight the Romans. It’s probably something like that. But anyway, let me pass beyond that and get back your question.

When people ask me what is my job description, what do I do? And my answer that I’ve come to over the years is, ‘I’m a servant of the muse.’

And that’s my answer to what is it really about? And what it’s really about is, I believe that we are put on this earth with a bit of a destiny, and that just as your books, you have books that you were born to write, and that are on the bookshelf behind you, and you have books in potential on the bookshelf ahead of you.

I do too and so do all of us. And I think I’m just asking the question of the goddess, ‘What do you want me to do next?’ And I just try to believe that she has some kind of plan.

If you think about Bob Dylan’s albums as a total through line, or Bruce Springsteen’s, or the Beatles or anybody like that, the body of work is saying something. And I think a lot of times, the artist herself or himself doesn’t even know. We don’t even really know what this is really about, but all we can do is try to follow that, I think.

There are a lot of writers that don’t work like that. A lot of writers write for hire, or they try to second guess the market. They say, ‘Oh, the market wants this, let me give it to them.’ Or, ‘I can get a job working for So-and-so. He wants me to do this so I’ll do that.’

I understand that and I respect that. But my own style is, I feel like I was put on this planet to write something, I don’t know what. But book, by book, by book, I want to let it unfold. And that’s what it’s really about for me.

Joanna Penn: I love that books have potential that you said there because I feel that too. I feel like there are so many ideas. At the moment, in fact, today I was just writing out, ‘This paragraph is this book, this paragraph is this book. And which one should I do next?’

I want to ask you that because you’ve written lots of fiction and non-fiction, and your audience are people in the military, to historical-fiction readers, to writers, to artists. And I wonder, how do you know, or how do you decide which book to write next? Whether it will be a non-fiction to help writers, will it be another historical fiction?

How do you know what should be your next project?

Steven Pressfield: It’s another great question, and I still don’t have a real absolute answer for this. Usually the way I go for it is, I ask myself, ‘What am I most afraid of? What upcoming projects scares the crap out of me?’ And I say, ‘That’s the one I got to do.’

But again, Resistance with a capital R is so diabolical at fooling you, that it can fool you. A lot of times, I will know for sure because I get seized by something and I just have to do it. And usually, in that case, it’s usually an idea that I think is really stupid. And I usually think, ‘This is never going to sell. This is the lamest idea. This is not commercial at all.’

But I’m seized by it. I almost always have to make a decision of like, ‘Okay, I don’t care. I’m going to put in two years and if it totally flames out, so be it.’ Usually, those are the ideas that actually work the best. Don’t ask me why, I have no clue.

So that’s easy when you’re seized by something, but other times, it’s a lot tougher. There’s that early period, maybe the first few months, where you’re pushing through something and I’m in kind of a case like that right now with another book that I’m thinking about, where you just, each day you finish and you go, ‘Is this any good? Am I getting anywhere? Is this the dumbest idea? I don’t even like it, why am I doing this.’

But a lot of times, after three months or four months or something, you’ll start to get traction on it. You’ll go, ‘That was just a period of doubt. That’s all it is. That was just Resistance, and I just had to push through it.’

Joanna Penn: I think that’s really encouraging and in fact, I went to your blog and I think this is the one you were talking about. You said you’re having a hell of a time even conceiving it and, ‘I’m not even sure what to include in this damn thing.’ [Resistance and dreams on Steve’s blog]

And I was like, ‘Wow, it’s so great to hear that you suffer from this and the doubt.’ Because people think that it goes away. That, maybe, once they’ve written one novel, that it will just go away.

Do you know any writer who has got over that kind of self-doubt?

Steven Pressfield: I don’t actually. There does just seem to be that period of self-doubt at the beginning of a project. This one I’m working on now is basically, it’s Diana, my girlfriend, is encouraging me, ‘Oh, this is going to be wonderful, you got to do it, you got to do it.’

And I’m just saying to myself, ‘I don’t know, I just don’t know.’ It’s an autobiographical thing. I’m going to be telling about certain things that happened in my real life. And of course I’m thinking, ‘Who cares about this, Steve? Who wants to hear about these dumb things that happened to you? Write a novel. Do something.’

Oh, here is one thing I want to say. Maybe this will help our listeners who might be going through the same thing. The thing that has really helped me in here is listening to my dreams. I’ve had a couple of those dreams that wake you up and you just know they’re important dreams.

Both of them have encouraged me to have faith and to keep going after I’ve finished analyzing them. I take that really seriously because I think that’s our soul communicating with us, our unconscious communicating with us. So that’s one thing that keeps me going on this thing. Although I’ve had to set it aside, like I say, because of promoting A Man at Arms. But I’m now anxious to get back to it. It’d be so great to get back to just writing.

Joanna Penn: I understand that.

Someone actually asked me about this just yesterday, how do you know when a project is worth continuing with, and when do you give it up? And I haven’t given up a story I’ve started writing, but I wondered because you said you have these different outlines.

Do you give something up before you start, or do you ever give up a project when you’ve actually put time into it?

Steven Pressfield: I’m like you, Joanna. I think once I’ve gotten into it, I almost always finish it. I don’t know if that’s a bad idea or not.

Joanna Penn: Stubbornness?

Steven Pressfield: I usually drop projects in the early stages. And I’m just asking myself, ‘Is this a good idea?’ If I just can’t get the enthusiasm going forward, I’ll just put it aside.

But I’ve also found, sometimes that those projects, if you come back to them a year later, suddenly you go, ‘Oh, that’s a pretty good idea, I don’t know why I threw that away.’ Maybe sometimes it just takes a few iterations for something to gain traction with us. But I think, basically, once I start on something I’m like a terrier and I just won’t let it go.

Joanna Penn: Me too. And I think it’s one of those Heinlein rules, isn’t it? ‘Finish what you start.’

Steven Pressfield: Oh, I like that.

Joanna Penn: Who knows where it will go?

Steven Pressfield: I do think if you put a lot of time into something and you do quit, it’s a bad thing. It’s bad karmically in some way. I’d rather finish it and have it fail, than assuming I’ve put in a lot of time not just a little time.

Joanna Penn: You mentioned about doing some more autobiographical work and you’ve put a lot of your personal life in a lot of your books. I’ve read most of your books and you really get that sense of your history in that as well.

How difficult is that for you to be really honest about yourself and your failures in some sense, and your triumphs. It’s much easier to do it through a character, right?

Steven Pressfield: Yeah.

Joanna Penn: Why do you do you do that? What do you think drives you to share those personal things?

Steven Pressfield: I think in The War of Art or in other books that are about writing, almost every story that’s about me is a failure. There’s practically no stories of success. And the reason that I do that is I want to help the reader, I want to encourage the reader.

Because most of us, when we’re reading a book like that, we’re thinking about our own failures. Not even stuff we’ve finished that failed, but stuff we never even got started, or stuff we procrastinated, stuff we sabotage ourselves on. I think it’s encouraging to read somebody like me telling you, the same thing happens to me over, and over, and over.

It’s like one of the things about social media, Facebook, and Instagram, and stuff like that, is people only put out their best selves. You see the picture, they are on the beach at Saint-Tropez or whatever, toasting with champagne and everybody, the rest of us who are watching, and we go, ‘Oh, I hate him.’ Or, ‘My life is meaningless.’

But I think it’s really empowering when you tell a story about a failure. Empowering to other people. Because they can say, ‘Okay, if it happened to him, then it’s okay if it happened to me.’ Most of life, I think, is failure, and just getting up and trying again.

Joanna Penn: Certainly, the writing life, as you say, you put in your effort on your books. And am I right in saying The War of Art, for example, was not a success out the gate.

Steven Pressfield: It took a long time. I would say between 10 and 15 years before it finally… It just started. It just was a word-of-mouth thing, very, very, very slowly.

Joanna Penn: Well, then, I have to encourage you about A Man at Arms. If all your promotional stuff means that those couple of months are slow, it may take some time.

Steven Pressfield: Well, that’s true. In fact, it’s happened. Gates of Fire, which is ‘my biggest success’ that took forever. That took another 10 years before it finally, little by little found an audience.

Joanna Penn: I think that’s very encouraging.

Steven Pressfield: Which unfortunately, a lot of times, it would go out for 10 years and they don’t find anything.

Joanna Penn: This month it’s actually my 10th anniversary of my first novel coming out. So I feel like, ‘Yay, I’ve put in a decade, it’s the beginning!’

Steven Pressfield: That’s great, congratulations, Joanna. That is great.

Joanna Penn: It’s a start.

Before we finish, I did want to return to marketing because we did start that way. Now, you’ve been blogging for at least a decade, I think. You’ve been blogging a long time and you’ve, obviously, been learning so much and you’ve been doing this video series on the warrior archetype, which is great.

Some people should definitely go look at that. It’s got the practical stuff but also the more psychological spiritual angle. How have you seen this content marketing, the blogging, the video, play into your book marketing?

Do you see any direct result or is it something that you do for your own creativity as well?

Steven Pressfield: Another great question, Joanna. I say it’s maybe 50/50. That I’ve certainly learned more than I’ve taught from my blog that’s about writing, but at the same time, I do think it really does help to have something out there that…or to establish relationships with people who will come to your blog or come to whatever it is.

It’s a really fine line for me because I hate to just be selling. A lot of what I do on social media and stuff like that, I feel like I’m giving. I’m putting something out there that I hope will either encourage other writers, or artists, or entrepreneurs, or will give them a little insight into the craft just like what you’re doing.

90% of what you do is helping people, ‘Here is how to do this. Here’s how to do that. Here’s how to deal with this issue. Here’s how to deal with that issue.’ Let me ask you, Joanna, how do you feel for the stuff that you do? Let me ask that same question to you?

Joanna Penn: I make a living because, as you say, 90%, even 95% of what I do is given away for free. And then a certain number of people support the podcast, they buy the books, they buy courses, they support our fiction.

I’m absolutely a supporter of content marketing because I feel like we can express ourselves creatively. I love talking to you and we’re getting something from this, but also the listeners are too, so it’s a win-win. To me, that’s why I love content marketing.

Steven Pressfield: I’ve never even heard that. That’s what it’s called, content marketing, huh?

Joanna Penn: Yes. There you go.

Steven Pressfield: How would you define that?

Joanna Penn: It’s giving away something for free so that you attract your target audience who then, a tiny percentage of them, might actually go on and buy something, but enough of them do to support your book launch or your whole business. It’s the foundation of my business, essentially.

Steven Pressfield: I guess it’s really the foundation of mine in that sense and I never even heard that. It’s a great term. I’ve got to think about this a little bit more.

Joanna Penn: There you go. Well, that’s fantastic. Tell people where they can find A Man at Arms and all of your books and everything you do online.

Steven Pressfield: First, if you just go to my website StevenPressfield.com. I’ve learned this thing. I never knew what a splash page is. Do you know what a splash page is, Joanna? You must.

Joanna Penn: Yes. It’s like a landing page. Your site looks great now. You’ve had it redone. It looks brilliant.

Steven Pressfield: Yes. That was Diana who did that actually. So if anybody goes to stevenpressfield.com or www.amanatarms.com, it’ll take you to this landing page/splash page that’s really all about the book, and the bonuses that we have, and the pre-order bonuses, and it’s got anything anybody would need.

And then underlying the splash page, and I never knew that this worked before, is my regular website. That you would have to click the big X up in the upper right-hand corner and it takes you to the underlying website. And that’s about my normal ‘War of Art’ type of stuff. But stevenpressfield.com or amanatarms.com will take you to everything.

Or follow me on Instagram @steven_pressfield. I’m doing a lot of stuff on Instagram. And a lot of it is about giveaways that we’re going to do and a little contest that we’re going to have.

Joanna Penn: Fantastic. Thanks so much for your time, Steve. That was great.

Steven Pressfield: Joanna, it’s always great to talk to you. Any time you want me on, I love to do it. It’s great to talk to you. And thanks for the great questions. I hope it helped everybody.

Joanna Penn: Definitely.

Steven Pressfield: Thank you so much. It’s great to be with you.

The post Warrior Of The Blank Page. Writing, Marketing And Mindset With Steven Pressfield first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn