In a little over two months, we the people will choose the forty-fifth president of the United States. Between now and then, the nominees will present their policy proposals and debate the issues, shaping a national conversation about some awfully big and important topics. But before we get to those televised debates (the first of three is scheduled for September 26 at Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York) we wanted to give some of our most thoughtful and articulate citizens—poets and writers—a chance to offer their perspective. Because, as former U.S. poet laureate Rita Dove remarked, “Our nation needs to learn to value its independent writers and artists as the heralds of a richly textured, inclusive national identity.”

The request was simple: Imagine you are face-to-face with the next president—whoever that may be—and, in a few sentences, write about what you hope to see addressed in the next four years. It turns out something pretty great happens when you ask writers to convey, without a lot of political grandstanding, what is most important to them. The contours of some of America’s biggest issues—education, health care, gun violence, racism, immigration, and the environment among them—start to come into sharper focus, the collective discourse rises above the rhetoric of political pundits, and the pomp and circumstance of the political process falls away, so that we are left with a discussion of real problems, real concerns, and, if not solutions, then at least some honest ideas that may inspire action of real, lasting value.

Dear President,

“The countless complex problems facing the world require complex critical thinking. Please reinvest in public higher education systems like UC, SUNY, CUNY, and the other once-strong and accessible state systems of higher education. Restore and privilege humanities and arts education at the K–12 and higher-ed levels. Reduce the military budget and make a real commitment to social and educational infrastructure.” —Kazim Ali

★

“Please listen to the stories being told right now by the scientists who study, and the citizens who live, amid the catastrophic changes taking place across the planet. They are not fiction; without courageous leadership they will become fate.” —Steve Almond

★

“Your critics, most of them, would have called me a superpredator back then, when the memory of the pistol was heavy in my palm—so that’s not my focus. But now, unlike then, you have power, and I’m left to wonder what you will call the young men and women lost in the system, those who walked down paths they regret. Do they earn your scorn, your mercy?” —Reginald Dwayne Betts

★

“I would like President Clinton to know that I support her and her agenda fully, especially as it relates to education, the arts, and the environment. The single greatest problem facing our species is the erosion of the environmental conditions that allowed us to evolve and thrive and tap out messages like this one on our phones and computers. We are doomed, yes, but later rather than sooner, I hope.” —T. C. Boyle

★

“Once the body arrives in the world it immediately becomes fragile—fragile in that it needs nourishment, protection, education, and endless chances; bodies of color, in particular, have had these basic human rights revoked, and it continues. I call for a protection of these bodies through a reassessment of the justice system and retraining of authorities who violate the civil liberties of citizens of color through racial profiling, stop-and-frisk, and abuse; human life is at stake, and my wish is that the next four years will reflect back the beauty and not the wreckage of our existence.” —Tina Chang

★

“America has often seen itself as a beacon of democracy, but the American project has always been about a settler project of inclusion and exclusion: democracy for those imagined as real Americans, and inequality for slaves, immigrants, black and brown bodies, and those who live in places the United States has colonized or destabilized, most recently Iraq and Libya. I hope that you can see yourself not just as a standard-bearer for a global economic elite, but as a force for equality and justice for all.” —Ken Chen

★

“There’s so much I could ask of you—a list of demands—but first to ensure our safety as citizens. Too many lives have been lost to gun violence—mass shootings, gang related, and otherwise—and now it is more than a false dilemma, it’s a reality that can no longer be ignored.” —Nicole Dennis-Benn

★

“There is no present or future without immigrants; white supremacy (and all of its sequelae) is one of the gravest threats to our democracy.” —Junot Díaz

★

“I want an America with tougher gun laws. I want an America that nurtures and embraces diversity.” —Chitra Divakaruni

★

“Eight million metric tons of plastic are dumped into the oceans every year. Our government has to get involved in legislation that reduces one-use plastics, invests in alternative-packaging ideas, and dramatically decreases pollution in the oceans, or by 2050 there will be more plastic in the sea than fish.” —Anthony Doerr

★

“If we are ever to attain our forefathers’ aspirations for ‘a more perfect union,’ educating our young—not only in the sciences, but also the arts—cannot, dare not, be neglected. If our children are unable to say what they mean, no one will know how they feel; if they cannot imagine different worlds, they are stumbling through a darkness made all the more sinister by its lack of reference points.” —Rita Dove

★

“I would say to the president that she should work to dismantle the global culture of corruption present at all levels of society, which prevents any meaningful change or accountability, and whose primary victims are the powerless and disenfranchised. This complicity is a symptom of larger systems of discourse and economy that exist to preserve the status quo, and I would say that in the absence of means to transform those systems outright, she should start, at the level of the law and of media, to model ways of addressing concrete problems with transparency and tenacity, showing that even at the most entrenched levels of corruption, change can be effected.” —Robert Fernandez

★

“The stakes are too high for you to ignore the grievances voiced by those of us who believed you when you spoke of progress and equality. We can’t afford for you to go slow.” —Angela Flournoy

★

“Climate change—stop dicking around. War—use only as the ultimate last resort.” —Ben Fountain

★

“I’d like our next president to know compassion and compromise. I’d also like her to know how thrilled I was when I received a thank-you note from her husband after I sent Chelsea a birthday card when I was fifteen.” —Carrie Fountain

★

“The occupation of Palestine by Israel—mass incarceration, presumption of guilt, withholding of resources, wanton destruction of human life, all underscored by the creation of physical barriers and the emotional propaganda of persecution, exclusion, mythmaking, and fear—are mirrored, one by one, in the policies of institutionalized racism in the United States. Unless we face this singular fact, and acknowledge our collective culpability as architects and sponsors of state terrorism here in our American cities, and in our foreign policy regarding Palestine (which is the bedrock of all other foreign policy), we will continue to be unable to fulfill the potential of our democracy for our people, and remain excoriated abroad for our impotence and hypocrisy.” —Ru Freeman

★

“Dear Madam President, our undocumented families are not silent or invisible in our hearts. May they be just as present in your actions as we continue to build this home, this country, together.” —Rigoberto González

★

“None of the problems of this country will be solved without things getting messy, and without your commitment to listen, truly listen, and to govern for the people who have the least in this country—black and brown women of color, undocumented women, trans and lesbian women, poor women, the people you usually wish to have behind you at a podium but rarely invite to the room where decisions are being made. Invite us in and listen and then act.” —Kaitlyn Greenidge

★

“President Clinton, after celebrating with a tall flute of Prosecco, please make gun reform your first order of business. In four years, I hope to live in a country where the pen is mightier than the gun (and the money that keeps it in power).” —Eleanor Henderson

★

“Ms. President, I want you to know that the power of having our first woman as president doesn’t escape me; I’ve been waiting for this my entire life. And I want you, as the first woman president of the United States, to place the liberation and justice of historically marginalized people at the center of your work—

terrifying, hard, necessary work. We need this more than ever.” —Tanwi Nandini Islam

★

“I would like the next president to know that the 2016 presidential campaign has awoken a sizable portion of this country’s electorate to the limitations of a two-party system that is beholden more to its own status quo than the interests of its constituencies; that we are more awake than ever to the corruption of politicians who claim allegiance to ‘the people,’ but whose votes and policies are purchased outright by producers of weaponry and manufacturers of economic disparity. I would like the next president to know that we will be watching and taking note of their promises to Wall Street and the military-industrial complex, that we will call out their positions on trade deals that betray American workers, their complicity with a prison-industrial complex that seeks profit from incarceration, their commitment to a justice system that frees criminals in uniform while killing people of color with impunity, and that we will organize beyond their scarecrows of fear to create a movement capable of replacing this oligarchy with the highest of this nation’s ideals: democracy.” —Tyehimba Jess

★

“Madam President, thank you for sparing us your opponent’s dismal and clownish stupidity, his blind and blinding hate. I’m still scared, though. I’m scared that you think beating him will be the hardest part of your job, and I’m scared of what’s happening to the environment, to our schools and water supply and our tolerance, scared of people being out of work and people being hooked on painkillers and people not being allowed to use the restroom where they feel most comfortable. I don’t give a rip if you’re honest or transparent or running a thousand different e-mail servers, but I need you to be compassionate and smart and clear-eyed, to be decent and flexible and open-minded, to be afraid with me—with all of us—and despite our fears, not least yours, I need you to be brave and resilient and, well, hopeful.” —Bret Anthony Johnston

★

“I’d like to talk about government subsidies for mental-health care. We tend to speak about mental health after some extreme event, like a shooting spree, but mental health is an everyday thing. So many people—especially poor people and minorities—are suffering in silent pain.” —Tayari Jones

★

“Make fighting bigotry a priority—bigotry of all sorts, from race to sexuality to gender to class. I feel it’s especially the responsibility of our candidates this time around, as this very election unleashed a whole new wave of intense bigotry directed at all sorts of minorities—so I feel like it is the urgent responsibility of the elected official to face this and work to increase the dialogue, education, and awareness required to heal and advance.” —Porochista Khakpour

★

“I watch my students invest in cultural, economic, and financial change despite their pessimism and frequent belief that we live within a system that profits from their disenfranchisement. How do we convince the next generation of thinkers that their engagement and participation in the political system matters as they watch so much of the progress facilitated by activists of the past dismantled?” —Ruth Ellen Kocher

★

“Madam President, please pay more attention to, support, and build up public education. Our schools are the democratizing cornerstones of our communities—and this country’s future.” —Joseph O. Legaspi

★

“I’d like to trust that the voice of any suffering person, regardless of category, had as much currency with you as some power broker. I’d like not to doubt you knew that suffering was of a piece with the planet’s emergency, the ongoing story of oil, water, war, animals.” —Paul Lisicky

★

“Your country is complex; it is hard to imagine a foreigner being able to fix it for you. Keep this in mind when you consider invading another nation.” —Karan Mahajan

★

“What’s really important to me is the radical reconceptualization of our broken criminal-justice system that targets young black and brown people—increasingly girls and young women—for arrest, detention, and incarceration, thereby continuing the program of relegating generations of people of color to second-class citizenry. It is clear to so many of us that the increased presence of police in daily life, alongside the militarization of police forces, is the wrong path to go down, and that we have to think progressively in our imagining of the future we’d like to create.” —Dawn Lundy Martin

★

“Please put climate change at the front and center of our national conversation, and follow up by funding initiatives toward developing and using sustainable energy.” —Cate Marvin

★

“Peace is a good word for politicians to look up, understand the meaning of it, use it once in a while, learn to practice it. You are committing environmental child abuse by poisoning our food, polluting our air, and totally destroying the environment so that a few of your cronies can make a few extra billion or two while the rest of us will not survive even to serve you.” —Alejandro Murguía

★

“The blight on ‘American exceptionalism’ is the recurring cycle of black youth raised in communities where poverty, inadequate education, and insufficient recreational and job opportunities exclude too many of them from the promise of the American Dream. It is urgent that you fund programs now to address this shameful problem.” —Elizabeth Nunez

★

“Dear Madam President, help us lift up the least advantaged among us. Put your strength and determination behind education, jobs, and equality. We have benefited greatly from the moral guidance of the last administration. Please keep the spirit of ‘yes we can’ alive. God bless you.” —D. A. Powell

★

“What the world wants, demands, deserves, and needs from you is that you guide your leadership and base your decisions on just one principle: love. Because isn’t that the whole point to it all—love? Isn’t that why we all keep on going?” —Mira Ptacin

★

“Madam President, the influence of the Israel lobby is not as valuable as the lives of the many Palestinians who have been living in degradation and increasing terror under the Israeli occupation for the last half century, just as the influence of the NRA lobby is not as valuable as the lives of the many U.S. citizens who have been injured and killed due to gun violence.” —Emily Raboteau

★

“There should be a new cabinet post—Secretary of the Arts. For the inaugural six poets: European, Hispanic, Asian American, African American, Native American, Muslim.” —Ishmael Reed

★

“I want the president to know that we are tired of having our voices silenced and our needs unmet. I want the president to know that we want better gun control, higher minimum wages, recognition of women’s rights, better education, and most of all a greater sense of our shared humanity—unity, not division.” —Roxana Robinson

★

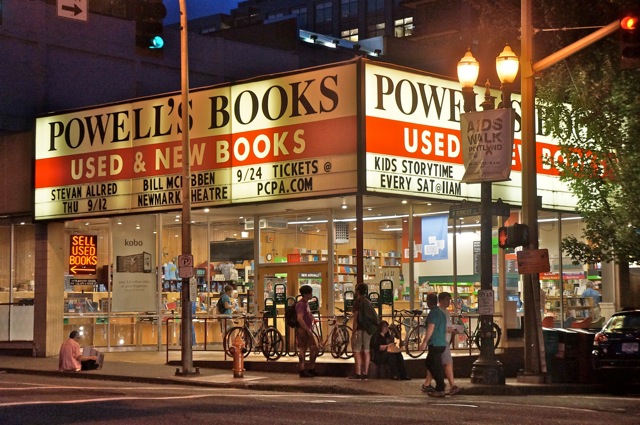

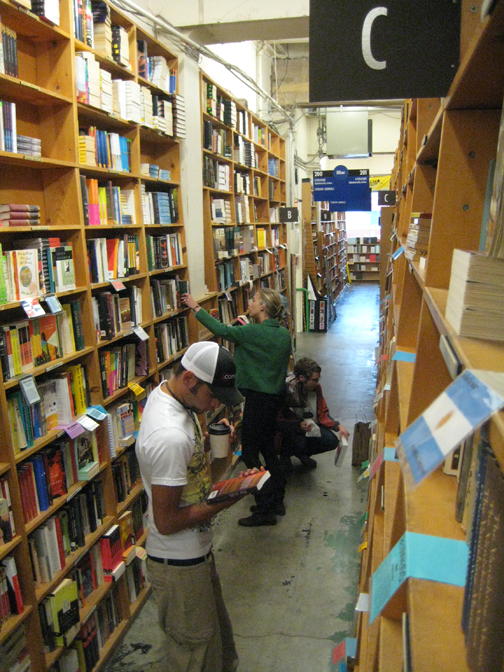

“President Hillary Clinton, I live in Portland, Oregon, where every day I watch our homeless camps grow in size. Homelessness is a national crisis that has barely been discussed this election season. You’ve pledged ‘to direct more federal resources to those who need them most.’ As you do so, please don’t forget about some of your most vulnerable constituents: homeless Americans. It’s an issue at the nexus of economic inequality, joblessness, rising housing costs, lack of affordable housing, health care accessibility, and systemic racism. Please make connecting all Americans to safe, stable homes and services a priority.” —Karen Russell

★

“Madam President, where has all the funding gone for arts in the schools? Could those kuts be the reesen we are all getin dummer?” —George Saunders

★

“The growing disparity in wealth in this country undermines any hope we have for achieving social justice. Changing this won’t be easy, and will require more courage, conviction, and political leadership than you have exhibited in the past.” —Dani Shapiro

★

“Since arts and humanities programs enrich our American lives beyond measure, connecting and inspiring people of different backgrounds and inclinations better than anything else does, it would be reasonable to support them threefold or more, without question. The fact that Bernie Sanders, a Jewish American, found it possible to be frank about the injustice and criminal oppression that Palestinian people have suffered for the past sixty-eight years suggests other politicians might be able to do this too—injustice for one side does not help the ‘other side’ and everyone knows this but does not act or speak as honestly or honorably as Sanders did.” —Naomi Shihab Nye

★

“I would like you to know that we do not have any more time—at all—to postpone addressing the issue of climate change. And while you’re working to ensure the survival of the planet, please remember that some of us are dying at an even faster rate from poverty, lack of health care, gun violence, police brutality, war, and twenty-seven kinds of intolerance—so please use your authority to help ensure that we live to see (and help implement) the climate-change solutions you set in motion.” —Evie Shockley

★

“I want the next president to shout from the housetops that violence is not a source or sign of strength but of weakness, whether inside a home or between nations. I want us to address violence at all scales, from domestic violence and gun violence to our endless, failed, one-sided, expensive foreign wars to the subtle violence against the poor and the unborn among our species, against more fragile species, and against the earth and the future that is unchecked climate change and the brutal fossil-fuel industry.” —Rebecca Solnit

★

“Did you know we need to find more jobs for the unemployed? Also, Palestine and Israel need to work it out.” —Tom Spanbauer

★

“If you can’t do everything, at least do what you say. I just wanna live in a country that knows the difference between love and hate.” —Ebony Stewart

★

“Our public-education system is in desperate need of resources, specifically in marginalized communities, as well as a more learner-centered, diverse curriculum emphasizing perspectives across race, gender, class, nationality, sexual orientation, ability, and the multiple intersections therein to challenge all of us to be better human beings on this planet. And, Madam President, if I can focus our last few minutes on my beautiful, complicated city: Your support of Rahm Emanuel terrifies me. Thank you for listening. Please, keep listening. To all of us. Not some. All.” —Megan Stielstra

★

“Free Leonard Peltier. Free Chelsea Manning.” —Justin Taylor

★

“No language is neutral. To speak is to claim a life—and often our own. If more Americans speak to one another, in writing, in media, at the supermarket, we might listen better. It is difficult, I think, to hate one another when we start to understand not only why and how we hurt, but also why and how we love.” —Ocean Vuong

★

“The greatest threats facing the United States are not terrorism and illegal immigration but rather injustice, bias, inequality, and fear. To be a great nation we must focus on criminal-justice reform; the eradication of the vestiges of slavery; education; and human and civil rights for all.” —Ayelet Waldman

★

“Please stop separating families through deportation; let it be understood that they did not want to be in this country to begin with (which reminds me, please stop bombing children, stop invading countries, stop sending the young and poor onto the battlefields). Please create a path toward citizenship for everyone, not just the ‘dreamers,’ because we all learn to dream from our parents.” —Javier Zamora

★

What were some of your best-selling

What were some of your best-selling

What’s different now that you’re coming on full-time as Guernica’s publisher?

What’s different now that you’re coming on full-time as Guernica’s publisher?

How has Amistad changed or grown in the past thirty years?

How has Amistad changed or grown in the past thirty years?