How do you turn an idea into a poem? What are the publishing options for poets, and how does marketing work? Rishi Dastidar talks about his life in poetry and provides tips for taking your creative work further.

In the intro, What Readers Want in 2022 [ALLi]; Ads for Authors (affiliate link); Submission on AI and copyright [ALLi]; How will Creatokia publish NFT books? [Creatokia Podcast]; AI for Voice series [VO Boss Podcast];

This episode is sponsored by ScribeCount.com, which provides automated sales aggregation from multiple publishing platforms, all combined into user-friendly charts and features, accessible in seconds. Whether you publish wide or exclusive, ScribeCount allows authors to customize reports to fit their individual needs. Check it out at ScribeCount.com.

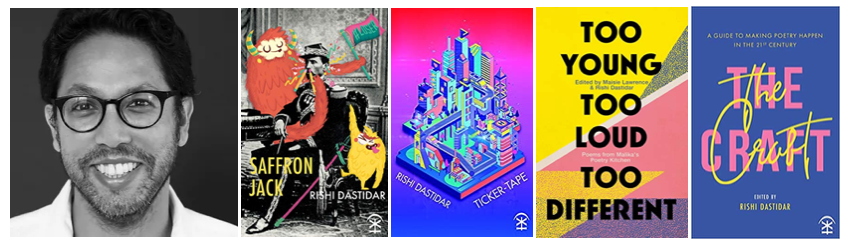

Rishi Dastidar is a poet, journalist, copywriter, and brand strategist, as well as the editor of The Craft: A Guide to Making Poetry Happen in the 21st Century, and co-editor of Too Young, Too Loud, Too Different: Poems from Malika’s Poetry Kitchen.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- How sound, images and word phrases affect Rishi’s poetry

- Tips and tools for capturing ideas

- Can we trust our subconscious to provide us with ideas?

- How to deal with dry creative periods

- The traditional publishing process for poetry

- The performance side of being a poet

- Pivoting to performing online during the pandemic

- The benefits of writers’ collectives

You can find Rishi Dastidar’s books at online bookstores and on Twitter @betarish

Transcript of Interview with Rishi Dastidar

Joanna: Rishi Dastidar is a poet, journalist, copywriter, and brand strategist, as well as the editor of ‘The Craft: A Guide to Making Poetry Happen in the 21st Century,’ and co-editor of ‘Too Young, Too Loud, Too Different: Poems from Malika’s Poetry Kitchen.’

We also both went to Mansfield College, at the University of Oxford back in the ’90s. So it’s been a while. Welcome to the show, Rishi.

Rishi: Hi. Good to see you. And, yes, it hasn’t been a while. We’re not going to dwell on how many years precisely, I hope.

Joanna: I know, it seems crazy. And it’s funny because I always ask, my first question is tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing and publishing. I still want to know that, but it’s funny because I feel like I know you from a snapshot in time. And of course, things have moved on for both of us.

Tell us about you and how you got into poetry.

Rishi: I arrived at college with the intention that I was going to do some form of writing once I’d left, and I just had no real idea of what that might be.

I ran around and did a lot of student journalism. I edited the student newspaper, edited the Student Handbook. And then after graduating, did a bit of journalism here and there. And that was fine.

Then I found my way into copywriting for brands and making ads. That’s the thing that really got me interested. That was all pottering along. And then, one day in about 2007, I had a proper Damascene moment in a bookshop in London, just off Oxford Street, where I picked up a book called Ashes for Breakfast by a German poet called Durs Grünbein. I started flicking through it, and I’d never seen language doing what it was doing on the page.

It sounds really naïve and strange to say that now, but I’d never read any contemporary poetry until that point. I didn’t know that you could do that with words on a page. I didn’t know that you could not go to the right margin, I didn’t know that you could leave lots of white spaces everywhere.

I bought the book there and then. I was just completely entranced and completely hooked. I knew right at that moment that that was the thing that I really wanted to write. By the end of that week, I’d signed up for a course at City Lit, a college in London, the introductory to poetry course.

That’s where the journey really started for me. I’ve been pursuing it and trying to get better as a poet ever since.

Joanna: Wow, I love that. I love how you said a Damascene moment, the pulling the book out, and your whole world was transformed. I love that. Because we know books can do that.

You said about the words on the page, and you didn’t know language could do that on a page. Of course, the layout on a page is only one aspect of poetry. So how does that shape the way you write? Are you thinking visually? Or are you thinking sounds?

How do you think about poetry?

Rishi: I’m going to give an annoying poet answer, which is, it depends on what you might be doing and what the language is doing at any given moment. Different poets will take a different view on this.

For me, it generally always starts with a combination of a phrase that is doing something unexpected to me, new to me, and the poem will emerge out of that. The phrase will start to suggest itself, you maybe free write into it, you maybe start to put other things together.

Generally, it’s arresting, because it’s also doing what? It’s doing something that’s visual. It’s painting an image.

I’ll give you an example. Last night, I was mucking around with the phrase that was something around like, cardinal reminiscence bump. And, okay, that’s just a three-letter word phrase. But you can hear within that there’s something interesting sonically going on. And there’s something interesting visually there as well. The idea of memory bumping up against itself.

The poem will emerge out of those twin impulses, the exploration of that phrase, where the sound leads you, where that image leads you.

You have to get out of the way a bit as well, just in terms of allow the poem to emerge, see where it comes out.

Once you have that draft, then you can get into more of those issues around, ‘Okay, what’s it doing on the page? Is there enough space? Does it need to be condensed up into one unit? Or doesn’t need to breathe down the page? Do I need to give it more space?’ You’re then into issues and thinking about things like line breaks.

How do I roll sense over the line? Where do I need to give it space to breathe? All those sorts of things. But it’s hard to deconstruct in the moment that you’re actually writing it or creating it. You just sort of have to let it happen.

And then it’s only after that you can then start to go back and go, ‘Ah, okay, so this needs to expand out more, this needs to be condensed more.’

Joanna: So that phrase that you mentioned there, is that something that you heard?Where do you even find these phrases?

Rishi: I’m very magpie-like in terms of how I’m going around the world and how I’m engaging with stuff that I read and hear. So that particular phrase is probably a misremembering of something that I read in ‘The New Yorker’ last week, I think, an interview with Wes Anderson, the film director, and he was talking about some of the inspiration behind his new film, ‘French Dispatch.’

Immediately, if something snags, you just have to write it down. Even better if you write it down incorrectly, because you’re taking it into a new realm.

It’s not necessarily the case that a poem immediately emerges out of that phrase, but the subconscious bit of you is going, ‘Ah, there’s something interesting there. I don’t know what it is. I might not know what it is for 20 years, but I need to have it now.’

So it’s there in my bank of stuff to be revisited later on. I will do that with headlines, with taglines and ads, with broken bits of commentary that you might hear in sports matches, and news reports, in people’s conversations that you might overhear.

Poets are great eavesdroppers. Never be around a poet for too long because one ear is always on what someone else is saying because you know that there is something of interest going on there. And of course, there’s always what we’re looking at in and around the world as well. Trying to find ways of making the familiar unfamiliar, or defamiliarizing it, making it strange so you can actually get to a deeper or a different truth about it as well.

Joanna: You mentioned the writing things down. I think writers are similar, whatever form you write in. Obviously, I write novels and short stories, but I write phrases down and lines and quotes in my Things app, which is on my phone. But also I use journals.

Where do you write down things? How do you capture those ideas?

Rishi: Oh, my system is so broken in terms of how it works. Right now, the most immediate thing is I have a little list app on my phone and that tends to be the first place where things get scribbled down. If I think that something longer is emerging in the moment, I will move it to the Notes app on the phone, and that will have a lot of stuttering first drafts on it.

There is a work-in-progress notebook that always comes around with me and is currently in my jacket pocket. And then for stuff that I know, if I’m not going to do anything with right now, I have a bright orange notebook, sort of Moleskine type thing, which sits somewhere. That’s my Spark book type thing where all those sorts of errant phrases that don’t have a home yet, or ideas just sort of get parked. So that’s there.

Then I’ve got a drawer in my desk where fragments that could coalesce into bigger ideas, and sketches of poems or sketches of other projects, they tend to get shoved in there.

And then there’s some weird sort of triage system that happens as ideas gather along with each other and things will get pulled out the drawer and put to the one side of the desk and gradually out of all that something bigger starts to cohere together. I frankly have horrified myself just trying to describe that there.

Joanna: You probably find this too, I’ll write all this stuff down. And then so often, what I’m actually working on has no relationship to the stuff I might have written down. And then I might discover, years later, like I discovered the idea for my first novel, which I thought I’d had that idea in 2009. I found it in a journal from around 2003. So I’d had the idea before, I’d forgotten the idea, and then it had come back in my subconscious somehow.

Can we trust that the important things will come back even if we think we’ve lost them?

Rishi: I think so. I think it’s also a case of trusting that they will come back when the time is right for them to come back and that you as a writer have sufficient by way of skill, ability, stamina, desire to actually get that idea out there.

I’m always more worried if it feels like I’m not coming up with ideas. That’s when it’s like, ‘Oh, has the well run dry?’ You go through periods like that where nothing is necessarily firing your interest or whatever. But gradually, it does cycle back round.

Especially for a poet, planning for a poet is almost an anathema. I really don’t know what the books look like until there’s a certain sense that you’ve nearly got everything that you need. And it can start to cohere into a bundle that looks like 60, 70 pages that starts to talk, where the poems start to talk to each other. That’s not a rational process at all. That is very much a subconscious emotional process more than anything else.

Joanna: You did just mention about a bit of a worry if you aren’t coming up with ideas, and as we speak, we’re still in a pandemic, and a lot of people have struggled. I’ve struggled because I get a lot of ideas from my travels, all my books are about my travels. My well ran quite dry. That was the first time I’d been worried about it really in the last decade.

How do you deal with those dry periods? How do you kickstart things? Do you actively go looking for stuff?

Rishi: I think it’s slightly a delicate balance of actually is their emotional energy and bandwidth. So a lot of the over the last 18 months, 2 years, it hasn’t felt as fertile or productive a time, in part because it’s been so busy at my day job.

It’s not felt that there has been much space for things to leak in, like moving around, going to different cities is a lot of where my inspiration and observations comes from. So that has been hard.

There is always reading to be done. There is always learning from other writers to be done. And so even knowing that, okay, I might not be writing as much right now. But it’s a chance to actually catch up on so many great books that have been published over how many years.

The more that you read, the more that you will get fired up again because you’re seeing what other people are doing, how they’re experimenting, how they’re addressing different subject matter. And, again, the process is not direct, but someone will do something and you’ve launched that away and go, ‘Okay, that’s an interesting way of attacking that subject’ or, ‘Okay, that’s an interesting way of tweaking that form. I haven’t thought of that.’

Even when it’s not necessarily coming from you, you know that reading as your superpower means that you can always get something that will benefit you later on.

Joanna: Absolutely. And then, this might be a difficult question, but when do you know when a poem is finished? Because I feel like the tinkering of language is something that poets enjoy so much.

How do you know, yes, this poem is finished?

Rishi: The cliché being that a poem is never finished, it’s only ever abandoned. It’s different for every poet. I can characterize it no better than you have to have your spidey sense working. And it sounds mystical nonsense to say it, but the poem will generally tell you when it is finished.

The best that I can characterize it as is that every poem has a certain type of energy. And what you’re trying to do through the drafting process is maintain that energy, and make sure that the poem achieves what it wants to achieve within the space that you’ve given it.

There is very definitely a point you will over-tinker, where you can take out one word too many, add one word too many change a piece of syntax or punctuation, and that energy starts to leak away.

That’s what I’m always looking for.

Does it now feel enough on the page to me, or does it still have a liveliness and the spring to it that makes me still want to read it?

And the frustrating thing is, you can’t really formulize that. Sometimes it will take 17 drafts to get there. Sometimes you can be done in four, five.

You just have to be alive and alert to that. And of course, that’s just your judgment. I’m very fortunate to work with a brilliant editor, Jane Commane at Nine Arches Press. You end up relying a lot on that judgment as well because they’re coming to it cold.

They’re not going to be as close to it as you are and so they will be able to see things which are screamingly obvious in terms of that need to be changed that are wrong as well. So the process is never just wholly reliant on you, but it’s sort of 90% reliant on you. You have to develop that sense of judgment that the thing is done.

Joanna: You mentioned a bit ago about the 60, 70 pages, which is when you have a collection, I guess, and poems start to talk to each other somehow. I got your poetry collection Ticker-tape and was having a look at that. And obviously, you play with these different forms on the page, I got it as an ebook.

As an ebook, we can’t control the look of the page as much as you can in a physical form. So what’s your process of publication, because a lot of people listening are both independent authors, but also have traditional contracts and things like that. And we all do different formats.

How does your traditional publishing process work?

Rishi: I’ve reached the stage in my relationship with Jane where I trust her implicitly in terms of the feedback and the steer that she gives me. So I will always listen to her.

Generally, I will have a loose idea in my head in terms of a theme, and arc, an idea that a book might want to carry. And then it’s a process of roughly pulling things together that might speak to that. I do that in quite a quick flurry.

And then I email that very rough first manuscript to Jane very hastily, and just basically saying, ‘Take it off my hands, I don’t want to see it again.’ And because the lead times in poetry are so long and slow, there’s a lot of time for things to basically sit and mature, and wait. So if I give you an indication, we’re working on my third book at the moment, and that’s not due to come out until 2023.

Joanna: Wow.

Rishi: We’ve got a lot of time just to actually play about with stuff, take poems out, reorder stuff, rewrite. But we agreed that we’re not going to touch it for a year. So the manuscript is just sitting and waiting.

When we do come to it next year, we’re going to attack it with a fresh vigor and come to it cold. That’s an indication of just one editorial relationship.

The good thing about poetry, of course, is that, especially now, the means of getting out there, and getting your work out there, and getting to market, are so much more wide and wildly varied than they ever have been.

I work in a relatively traditional manner, directly with an independent publisher based up in Coventry. It’s a non-agented relationship, so I was fortunate that I sent Jane some poems and she liked them so much, she wanted to publish the book, which became Ticker-tape, and we’ve developed the relationship from there.

There are plenty of other people that work in different ways that go to the web as their port of call. Of course, self-publishing, maybe using social media as another means, using YouTube as another means of getting work out there.

How you publish and how you get to market is really ultimately dependent on what it is that you want to achieve, and what you feel the best form for your poems are.

There are plenty of poets writing, for whom actually a book is not even close to being the end goal because the poem is the poem and actually standing up performing it, it hitting the air, that’s the important thing, and the book is an afterthought.

There are poets like me who, because we’ve come up through what’s called the page tradition, the book is the object has always been the ultimate goal. We work towards that end instead. So it is sort of dependent on you as a poet to have an idea of what it is that you might want to do, and where you might want to take your work as well.

Joanna: Before we started recording, you said about that you do spoken word, and you do go and perform in order to sell books, which I thought was really interesting.

Tell us about the performance side of being a poet.

Rishi: Especially in British poetry, there’s always been this divide between people who’ve come up through what’s called the page traditions, or people who’ve published in magazines, probably, studied creative writing, or English, or something like that.

And people who’ve come up through what’s known as performance of the spoken word, and there’s a historic overlay of race and class in that divide as well, which is probably far too complex to get into right now. Broadly speaking, and this goes back to the poet’s route is the traveling troubadour, going round, bringing lyric and song to village as you go around in the middle ages.

Broadly speaking, even if you’re a poet who is much more literary in approach, and bent, and wants to be known for the books, the number of books that you sell is so much smaller than compared to almost any other type of literature that is published, that you just cannot rely on publishing a book and it being in bookshops. And that’s it.

You have to go out and meet people. And you have to go out and read the work.

You have to go and organize readings, visit book shops, visit poetry nights, basically say yes to whoever will have you. So you have to learn some skills and some aspects of performance. Even if you don’t call yourself a performance poet, you have to learn those things of being able to project, being able to hold a room, being able to very crudely know how to use a microphone without breaking people’s eardrums.

There is a level at which you have to have some degree of stagecraft, some degree of I know how to construct a setlist, I know how to take people from A to B, in a given moment, I know how to make 10 minutes of time work, even if you don’t think of yourself as someone who is comfortable or natural on stage.

I’ve certainly found that out of everything, that’s been the aspect of craft that I’ve had to learn the most over the last couple of years, because I’m acutely aware as well that people are coming to our poetry night out of a welter of other entertainment options that they could be doing that night. They could be in watching ‘MasterChef’ or watching the football or something on Netflix.

The fact that people have chosen to spend time with poets and poetry, there’s an element to which you have to give them a degree of show. But that doesn’t mean that it has to be insubstantial. It can still be deep and serious, but there is that respect that you have to give the audience by turning up and giving your work the respect it deserves as well when it hits the air. So not mumbling, not keeping your eyes down on stage, that sort of stuff.

Joanna: Have you learned that through practice and doing things, or have you done courses and things on performance?

Rishi: It’s mostly through learning as doing it, and sinking, or swimming, whatever it might be. I’ve done a couple of courses to work on stuff like my breath, and just to feel more comfortable projecting and being able to take control of a stage.

I’m also fortunate that as part of Malika’s Kitchen, that collective, Malika Booker, the founder, Roger Robinson, the other founder, they’re two of our great poets, but they’re two great performers as well. I’ve worked with Roger and Malika in the past to actually build up my confidence in terms of how to take hold of the stage.

There was a reading that I did maybe getting on for about seven, eight years ago. Malika and Roger were directing that, it was like the soundtrack. That was basically a 2-hour masterclass for me in terms of how to take them and take them on the first stage for a 300 seat audience.

Some of the things that Roger told me that day, I still use it when I’m preparing a performance just in terms of keying and what I need to key into emotionally to be able to then transfer that to the audience. How I need to hold someone’s eye in the audience, how I need to find someone to direct the performance to for the evening, whether it’s five minutes, whether it’s half an hour, all those things you have to have at least a consideration of. It’s definitely something that I’ve mostly learned on the job.

I have had horror shows. I’ve had gigs where one person has turned up and, oh, my goodness, that’s a tough night for all of us concerned. I’ve done my time standing on tables in pubs when the football’s been on and tried to get attention that way. Everyone has to go through that sort of apprenticeship, without fail, and you have to tune into the absurdity of it and run with it or you don’t, I think.

Joanna: I’ve always remembered you as someone with good humor, and an ability to laugh. And my memories of you are laughing. It might have been because we were in the bar so often!

Rishi: Yeah, sounds true.

As serious as poetry is, and as much as it changes lives, and as much as it is an investigation of language doing different things under pressure, there is an inherently absurd aspect to it as well.

Of course there is, I think, and you have to lean into that a bit. Because very few of us are going to be geniuses at the level of Penny or Hughes.

For the rest of us who are toiling in their shadows, you might as well enjoy it. Otherwise, why are you doing it? That’s not to detract from the seriousness of the work, or the seriousness of what you are saying. But I think as much as you want to move the audience, you want to also leave them with their hearts a little lighter as well. I think laughter is a useful tool in your armory to be able to do that.

Joanna: Absolutely. Especially laughing at yourself when things are difficult, which I think we all need to do. You mentioned that obviously performing in person.

How can poets and other writers embrace the audio and video opportunities available now online? Especially with the pandemic.

Have you been doing a lot more online stuff in terms of multimedia?

Rishi: Yes. Come March 2020, it was very acute in terms of just the juddering way in which everything moved online. I felt that very much because my second book was due to come out of the week that we went into lockdown. So my launch party, all the gigs that I had lined up for that first couple of weeks, all canceled.

If producers were agile enough, some shifted online, but we were very much feeling our way, and that spirit of experimentation carried through. So I did things like, on the night of publication, I did a 20-minute set on Twitter via a periscope, just literally holding my phone up and just barking down that to the 50 of people who wanted to just spend Thursday night being shouted out by man in the crowd.

The last 18 months has seen iterations of doing that sort of thing. I think you’ve seen that people very rapidly have found ways of working that worked for them. It’s been very beneficial in terms of accessibility for people, both in terms of the fact that you can now provide captions, and the fact that you can get audiences but also perform for audiences in a much bigger locale than you ever could before.

I’ve done gigs for American audiences which would have been a lot harder even three years ago, just in terms of not having to travel and so you’re suddenly opened up to a different thing.

Performing down the line does bring its own set of challenges. I think the energy that you need to actually convey the personality that you might want to project down a Zoom call is actually a lot greater than you might anticipate than if you were in the room. I find online readings actually more draining than offline readings.

Learning how to make the most of the tech on the platform has been hard. Some people are better at it than others, even things like do you actually invest in ring lights? Can you actually make sure that your laptop is set up in the right height so that your eye line is level, as opposed to looking up or looking down? Things like that people have had to learn on the go, and people are getting better at it as well.

The best thing that you can do is, as ever, say yes to stuff, and then work out how to do it as you go along.

And not being scared of this stuff. And just go, ultimately, what’s the worst that happens?

You read some poems into a Zoom call, some people send some emoticons and emojis in the chat and then on you go. It’s not as scary as it first feels, I think is the main thing. Try and to embrace it.

Joanna: I think that’s great. I do agree with you that I think people didn’t realize how much energy you do expend it through a screen because you’re still trying to project, in fact, you have to project energy through the screen in the same way that you would in person.

I think a lot of people understand that now because people are like, ‘Oh, I just can’t do Zoom calls all day, it’s so tiring.’ I feel like ‘normal people’ in quotation marks now understand this as well as we do.

Rishi: Yes, absolutely. There’s something about most performances happening in different space. So you’re going somewhere, you have that time to prepare, you have that time to get to that headspace, as opposed to say, in my case, I’m working from my study. And then I maybe have five minutes. I have to try and get into the performance headspace. It’s a weird sort of decompression.

If I could do things, again, I think I would be a lot stricter with, okay, if I am performing tonight online, I need to treat it as I would have done a physical gig and so stopped work earlier so I have time to decompress from that. I can then build the energy up to do the performance again, as opposed to at 7:00 need to log off the work, email, and jump onto the Zoom call. These are things that we’ve only discovered as we’ve had to do them, basically.

Hopefully, it leads to much more by way of performance opportunities and differing modes of doing things as well. I really do hope that more producers will make more events hybrid. I’d love to be able to do more live in-person readings, but with people dialing in from all different parts of the world so you actually have this lovely mix of people and voices in the room but elsewhere around the world. That seems like one of the things that we should take away from the last two years that you can expand the possibilities.

Joanna: Absolutely. You talked about the poetry collection, Malika’s Poetry Kitchen. I love this idea of The Writers Collective, which I feel is not so common in perhaps the longer form book space.

Tell us about Malika’s Poetry Kitchen and how you work together in a collective.

Rishi: Malika started Kitchen…oh, we’re celebrating the 20th anniversary of The Collective actually. So that’s when the book came out. We’ve been doing lots of events in the weekend over the last couple of months to celebrate that fact.

When Malika started writing back in 2000, 2001, one of the things she quickly felt was that there was a definite lack of support for writers like her who were just starting, but also in particular writers of color who were just starting as well.

The poetry establishment at the time was very sniffy, very snobby, and had effectively placed poets of color in that box, which is, ‘Okay, you are just stand up performers, you’re spoken word people, you don’t have a sense of craft on the page. We’re not particularly that interested in helping you advance what you’re writing and how you’re writing.’

Kitchen started from Malika and Roger wanting to change that, and in a very DIY way, saying, ‘Okay, we’re going to set up something that means that we can help ourselves.’ It started in Malika’s house in Brixton. Malika and Roger invited a couple of other poets over who are looking for a similar thing. And it’s grown from there.

Basically, each week, one of them would organize some sort of workshop exercise where they’d read, they’d work through different poems, they’d bring crafts, they’d workshop those. From those small roots, it’s just grown, and grown, and grown, to the point at which poets from around the world come and give masterclasses to people in the group.

So many brilliant poets, who we read now who are winning awards and prizes have come through and been members of The Collective at the point.

It’s always been a free-floating thing. So you come and you’re a member for a bit, and then you move on, or you’re sort of a more long-standing member like I might be, eight, nine years or so now.

The key thing has always been mutual support. And the idea that we all learn from each other.

Crucially, we’re not trying to impose our tastes on each other, or all trying to write in a similar voice.

If you look at the book, and when you read the book, you’ll see that of the 70 odd poems in that, not one sounds like the other, which is just a testament to the fact that what we’re there to do when we round the table, is make everyone’s work better, and help them achieve what they’re trying to achieve in the work. But we’re not trying to impose our own aesthetic standards on it.

And through it, people have developed their skills in leading workshops, developing their performance skills, just developing their confidence and their ability to inhabit the position that says, ‘I am a writer, I’m a poet,’ which is often quite a scary thing for people to actually take on as well. I think there is a part, yeah, and I think why is it that there’s more sort of poetry help in that form. I think there is a practical thing here.

In two hours, we can get through a lot of work, we can get through a lot of people’s poems as opposed to looking at longer pieces over a longer term. I think we have more agility and fluidity when thinking about that, as opposed to thinking about big chunks of pros.

Joanna: Absolutely. You mentioned what the poetry establishment was like back in the early 2000s. Do you think things have changed now? In one way, we see some things changing in some ways.

Do you feel that the poetry establishment has changed and is more open now?

Rishi: Yes, it has. If I give you an example of how dire things were, the Arts Council commissioned Bernadine Evaristo in fact to write a report on the state of British poetry back in 2005. What she found was that only 1% of the collections published in the previous year had been written by writers of color, which was, in terms of representation was just stunning, a stunning fact, just one word, just gobsmacking.

Since that point, there has been a lot of money and effort put into bringing forward and bringing through writers of color. I’ve been a beneficiary of some of those schemes, so the cards on the table there. I think there has been over the last 15 years in particular, an acceptance that if your conception of what passes for poetry in Britain, is one that is very white, middle class, university-educated, you’re missing out on the wide richness of what is going on.

To the point at which now we’re seeing writers of color winning awards, getting their dues in terms of wider coverage as well. Roger Robinson winning the T. S. Eliot, a couple of years ago, Malika won the Ford prize for best single poem a couple of years ago, Kayo Chingonyi, being nominated for Forward and T. S. Eliot prizes.

I should stress these aren’t just mere tokenistic representations. These are brilliant pieces of work coming through that are finding their readers, winning the plaudits, because they are so good. But there is 15 to 20 years of graft that underlies that success, and opening doors, battering down doors when they won’t be opened.

I say to people now that if you are writing a history of British poetry, you can’t tell it credibly now without telling that story of how Black and Asian writers have contributed massively to it over the last 20, 25 years. I’m positive that there has been change. There’s always plenty more to be done, but I feel like the trend is going in the right direction, certainly.

Joanna: That is great and good to hear. And that poetry collection is Too Young, Too Loud, Too Different for people that are interested.

Tell us where people can find you and everything you do online.

Rishi: I mostly live on social media. Twitter is normally the best place to find me because that is where I hang out. And that is where I share most of my stuff. I’m @betarish.

I write occasionally for ‘The Guardian.’ So you’ll sometimes find me there. A route of doing poetry reviews, I do stuff for ‘The Rialto’ magazine. On occasion, Rialto is one of our best poetry magazines in the UK. So that’s always worth a dive in when it comes out, which is three times a year. I’m sometimes lurking on Instagram, but that’s mostly cat pictures.

Joanna: Tell us the names of your books so that people who buy your books can get them.

Rishi: Oh, well, that’s very kind, the invitation to flaunt myself. But yes, as you mentioned, Ticker-tape was my debut and that came out in 2017. And then my second book Saffron Jack came out in March 2020. And they’re both published by Nine Arches Press.

Joanna: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Rishi. That was great.

Rishi: Not at all. Lovely to speak to you again.

The post The Craft And Business Of Poetry With Rishi Dastidar first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn