Can artificial intelligence augment our human creativity? Will AI ever be able to create art on its own and would we even be able to appreciate it?

In this interview, Arthur I. Miller talks about the nature of creativity and The Artist in the Machine. In the intro, I mention my list of AI writing sites, and DALL-E by Open AI, as well as episode 518 on Writing in the Age of AI.

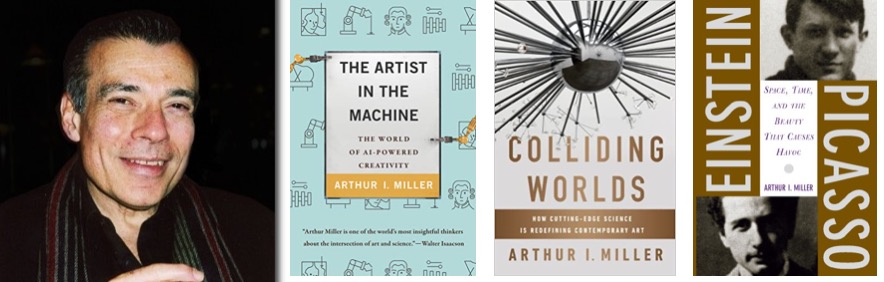

Arthur I. Miller, Emeritus Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at University College London, is the author of nine books spanning science, philosophy and creativity. Among them is Einstein, Picasso: Space, Time, and the Beauty that Causes Havoc, nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, and Colliding Worlds: How Cutting-Edge Science is Redefining Contemporary Art.

His latest book is The Artist in the Machine: The World of AI-Powered Creativity, which we’re talking about today.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and full transcript below.

Show Notes

- What is creativity?

- Examples of art created with AI across visual art, music, and writing

- Is AI a tool or a collaborator?

- Copyright issues with work created with AI

- What does the future of AI hold?

You can find Arthur I Miller at ArtistInTheMachine.net and ArthurIMiller.com and on Twitter @ArthurIMiller

Transcript of Interview with Arthur I Miller

Joanna: Welcome to the show, Arthur.

Arthur: Thank you for inviting me, Joanna. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Joanna: I’m so excited to talk to you since I read your book. I’ve given it to several people as well. It’s great.

Tell us a bit more about your background and why you became interested in creativity and AI.

Arthur: I became interested in creativity when I was a boy growing up in the Bronx. It’s a Bronx story. I was always a voracious reader and I made frequent visits to the local public library which was a magisterial building jam-packed with books and records, too.

One day I was reading at a table that happened to be next to the place where records were stacked. And on the edge of a row of records was one that particularly intrigued me because it had a picture of a man done in a pencil sketch, the man is deeply in thought.

I was always interested in sketching and then art in general. So I decided to borrow it, take it home, and practice copying the sketch on the cover. And I figured, well, since I have the record in my house I might as well listen to it even though I never heard of the composer.

I played it and it just blew my mind, with Tchaikovsky’s “Fifth Symphony.” I have never heard anything like that before. I began working back to Tchaikovsky and then gradually working back in time to other composers, too.

The question that was immediately on my mind was how did these people think up that magnificent music? And that’s what hooked me on creativity.

Growing up in the Bronx at that time, if you were smart or thought you were smart, you went into Physics, which I did, and I enjoyed the intellectual challenge. I wrote papers in it, on theoretical elementary particle physics, but my heart was not really in it.

What was always on my mind was those, what is the nature of questions? In this case, what is the nature of creativity? So I decided to change fields and I went into history and philosophy of physics, looking all the time into scientific creativity.

I read the original German-language papers in relativity and quantum theory. What jumped out at me, what leaped out of those papers was the emphasis on visual thinking, the emphasis on visual images.

At that time, there was the so-called imagery debate, whether images have a cause and effect on thinking or whether they are just epiphenomena such as you have lights on your computer, they flash on and off, if you broke them, the computer would go on anyway. I was in the pro imagery camp and it turns out that there were many cognitive scientists in that camp as well.

The way to deal with images, how are they manufactured in the brain, how are they handled in the brain, it was by use of the analogy between a computer and the workings of your brain. The issue was whether computers can tell you something about human creativity.

What occurred to me was can computers be creative? I wrote many, many papers on human creativity and I touched on machine creativity in them, too. This book concerns human and machine creativity with an emphasis on machine creativity.

Joanna: That’s fascinating and I’m sure you’ve seen the guys at OpenAI who created GPT-3 also created this DALL-E, a bit like Dali or WALL-E, and that actually brings in the image creation, which is so interesting.

Before we get into the AI side of things, what do you mean by creativity?

Arthur: My own theory of creativity emerged with my studies of highly creative people and it led me to suggest a two-step definition of creativity.

Creativity is the production of new ideas or artifacts from what already exist, and this is accomplished through the process of problem-solving.

Now indicators of how creative is the new object or ideas is whether they are surprising, novel, complex, or ambiguous. Those are judgments that are highly questionable in many cases, and so they must be handled with care.

I looked into problem-solving by using a four-stage method of problem-solving: conscious thought, unconscious thought, illumination, hopefully, and then verification.

Now the next question one must ask is what are the dynamics of creativity? What drives the creative process? What is the sine qua non of creativity? I call those characteristics of creativity.

Among those that emerged from my studies of highly creative people are competitiveness, perseverance, unpredictability, being out there in the world, having emotional experiences like falling in love, and problem discovery.

Then I could go on to discuss how machines can have these characteristics of creativity and so be creative like us. After all, why should creativity be an attribute and reserved only for human beings? And, incidentally, we don’t have to go to Mars to study alien life forms. They’re developing right next to us. And the astonishing thing is that we’re merging with them.

Joanna: Absolutely. It’s so interesting that you said about creativity, new ideas from what already exists. My audience are writers and we read things. We cannot just create from a blank mind. We’re not born writers. Obviously, you’re a writer too and we do our research, and we put things into our brain in order to output from our brain. So I think there is definitely some kind of a metaphor, similarity, but I know people have issues with that.

To get into some specific examples, quoting from the book, you say, ‘Computers are now finally beginning to create art, literature, and music in ways that exhibit not only their creativity but their inner lives.’

What are some of the examples of AI art that you’d like to share that you found particularly interesting?

Arthur: First of all, let me say that by ‘machine’s inner life,’ I don’t mean the machine’s hopes, dreams, and aspirations. It’s a little early to get into that discussion because machines don’t have consciousness or emotions. They will sometime in the future though.

Right now what I mean by ‘machine’s inner life’ is how it thinks and machines do have a way of thinking. And in that, their artificial neural networks adjust their parameters between their neurons when they learn and when they act on the world. And, similarly, so do we. The trillion connections between 100 billion neurons in our brain are continually being adjusted and that is thinking.

Machines learning, certain algorithms, have shown glimmers of creativity which, in itself, is a substantial step forward and here are some examples which I’d like to talk to you about.

The first is DeepDream. Originally, the algorithm DeepDream was invented to look into a problem that goes right to the heart of AI. We know artificial neural networks work, but we’re not sure how. DeepDream allows us to see what a machine sees as it’s analyzing an image. And what it sees is amazing, surreal, so different from what we see.

A classic image is the one that the inventor of DeepDream, Alexander Mordvintsev, originally used, to see what its code had to say. And it’s an image of a dog and an adorable cat against a verdant background. He put that image into an artificial neural network running DeepDream and having been trained on ImageNet, which contains over 40 million images of everything under the sun, cycled it, recycled it.

He stopped the analysis partway through at some layer of neurons. What did the machine see? The machine saw, instead of this adorable cat, a cat-like creature, some monster, sometimes called ‘the monster beast’ with two additional eyes on its forehead, two eyes on its haunches, dog-like attributes distributed over its body.

So what the machine sees is totally different from what we see and that should not be surprising because, after all, the machine is in alien form. The image that the machine sees goes beyond the image, it goes beyond the data. It is memory.

When a machine does that, when anybody, when we do that, we call it creativity. So why not attribute creativity to a machine? And from this work, an art movement has emerged which is still ongoing.

Another example of creativity, AI creativity in art, makes use of the algorithm generative adversarial network or GAN.

GAN, a generative adversarial network, is made up of two networks. One is a generator network that generates images from nothing or noise, and the other network is a discriminator network which senses those images as to whether they are true relative to what’s in its database.

Now the rejected images are sent back to the generator network and they form the memory of the generator network. And soon, the generator network generates images not from nothing but from its memory.

In this way, the generator network is dreaming. It’s imagining a world that does not actually exist. Now just as with DeepDream AI artists, this new breed of artists, an art movement has emerged that produces art that was thought that we could never have imagined without having machines.

A good example of AI-created music is the AI device called Continuator. It is an example of a machine and a human working together, each one bootstrapping the other’s creativity.

What happens here is that someone sits on the piano and begins to improvise. The notes are fed to Continuator which processes them into phrases and then the phrases are fed to a phrase analyzer which looks for patterns, and it is along these lines that Continuator, almost instantaneously, creates an improvisation in response to the human improvisation. And then the human piano player responds to the machine’s improvisation.

Improvisation is usually defined as a conversation between a human and a musical instrument. Here it’s defined as a conversation between a musician and an AI.

And now an example from AI-created literature. 2016 saw the first AI-scripted film called ‘Sunspring.’ Its creators named the machine that produced the script Jetson.

Jetson was interviewed by judges at a film festival in which ‘Sunspring’ was entered for a prize and, incidentally, it was in the top 10. Jetson was asked at the end of the interview, ‘What’s next?’ Jetson’s nomic reply began with, ‘Here we go. The staff is divided by the train of the burning machine building with sweat.’ Well, you get the picture.

But then, to everyone’s amazement, it concluded with a cogent statement, ‘My name is Benjamin.’ Creativity? Well, one would like to believe so. At any rate, from then on everyone called the machine Benjamin.

Joanna: I love that, and just to say, if people are wondering what the images from DeepDream would look like, there are some images in the book which is great.

When I was reading about the generative adversarial network (GAN), the idea of the generator and the discriminator feels a bit to me like first draft versus editing.

We generate this first draft and then our editor goes backwards and forwards with, how can I improve this? Do I want this? Do you think that reflects in the editing process?

Arthur: It’s not bad, certainly. The editor can be construed to be the discriminator network which then returns the manuscript to me or you, and then we redo it and so on until we approach what the editor, what it is in the editor’s memory at any rate, of what the manuscript should be.

Let me just go back to Continuator for a moment. In my book, there are videos that concern cases of AI creativity that I discussed. Obviously, you can’t get to a video through the book and Continuator is there, too, and you can actually hear this process and see this process. It’s rather amazing. The piano player himself is amazed by what Continuator produces.

Joanna: In fact, that Continuator process is how I feel, I think, when I’m starting to play with the natural language generation tools like GPT-3 and some of the people who are building tools on top of GPT-3.

What I’ve been doing is copying and pasting three or four lines of a novel of mine or a story of mine, and then hitting the generate button, and then it will come out with some stuff. And then I’ll be, ‘Okay. Well, I’ll riff off that for my next sentences.’ That kind of co-creation sounds a bit like the Continuator.

Arthur: Yes, it does. It does to a point. Yes, certainly. I think you used the word ‘tools’ in talking about GPT-3, as I recall, and I have to say that I cringe at the mention of AIs as tools, I’m sure you just meant them in passing because too many people speak about that in seriousness.

AIs are not tools, like paint brushes, or pencils, or paint in a can. Rather, AI devices are collaborators that can actually boost our creativity.

And may I say a word of introduction about GPT-3?

Joanna: Yes, please do.

Arthur: It’s the most advanced AI in the field of language processing. GPT-3 is an artificial neural network that was trained on roughly 500 billion words harvested from the web, from text, from blogs including social media, and tuned in with 175 trillion machine learning parameters. Text generation can begin, as you mentioned, with a prompt such as, how can I be more creative? And then a seemingly human-like text emerges.

Some caveats however. The emergent text can be riddled with factual errors, racial and gender slurs, and have left on its own GPT-3 gibberish. I can see that GPT-3 can help a writer having writer’s block. The writer can put into GPT-3 as a prompt the paragraph where the writer is having problems with.

But, again, GPT-3 can offer some help, but again right up to where? In fact, a lot of newspaper articles have been written using GPT-3, but you look into it closely and what the editor has done is put in a prompting sentence such as, ‘Presently, relations are tense between the U.S. and China.’

And then GPT-3 grinds out text. The editor will do this several times, and then take the best paragraph, and edit those paragraphs. Editors have said that editing GPT-3 is sometimes easier than editing a human writer. So in all, GPT-3 is correct 50% of the time. It fails as often as it succeeds.

Joanna: I’ve written nonfiction and fiction, and what’s so interesting with trying fiction is, of course, it doesn’t have to be correct, but it does have to be in some kind of logical way. But I’ve found some really interesting stuff coming out of it.

I do want to come back on your issue with the word ‘tools’ versus collaborator because I feel like if we use the word collaborator, so to me I’ve co-written a whole load of books with different humans and that I call collaboration with a human.

But when I’ve been playing with GPT-3, at the moment I don’t feel like it’s a collaborator. I feel like it’s a tool because I have to type the words in, I have to curate the output. I don’t feel like it’s a collaborator in the way that I would normally use the word.

When you use the word collaborator, given what you’ve just said with GPT-3, maybe it will be GPT-10 or something else in the future.

Arthur: Absolutely. Right now, by human collaborator, you may go out for a drink or dinner with, but, of course, you don’t do that with GPT-3. That’s far in the future when we have machines with emotions and consciousness, and volition, certainly.

But right now, I mean collaborator in the sense that it can boost your creativity. You can play with it, have fun with it. It can enhance your writing, but mainly it can offer you ideas for extending your own ideas. In other words, again, it can bootstrap your creativity and you bootstrap the machine’s creativity.

Joanna: That’s how I feel it is, is the idea of bootstrapping or building on each other’s words like you might do. But as you said with the Continuator, that seems quite cool.

I do find in the literary community that there’s much more of a pushback against the idea of using AI. What are your thoughts on that given that you’re also in the literary community?

Do you think that it can move from a scientific point of view to something that is about creating work for sale?

Arthur: Absolutely. There are a variety of devices. You mentioned Scrivener and ProWritingAid. But they’re not really creative devices. They’re used for editing your work.

GPT-3, of course, is a whole other kettle of fish that it can produce new text and who knows, in the future, GPT-10, 11, 12 may produce text that is good enough for you, for it to be your co-author.

Joanna: In the book, you give some examples of where music, particularly in poetry, are judged more harshly when they are known to be created by a machine. I know some authors who are publishing books already with tools like GPT-3 and some are happy to admit it, and others are not. Should we admit to co-creating with these tools?

Arthur: Well, sure. Why not? Certainly Scrivener and ProWritingAid are editing devices, they improve your text. One always thanks one’s copyeditor in the acknowledgment. So I mean, why not give a nod to Scrivener and ProWriting, too? They’re widely used. GPT-3 certainly deserves a mention. After all, this is the age of AI.

Joanna: That’s interesting then because I think there’s still an outstanding question. There is no official copyright law relating to works co-created with AI because for example, we don’t know whether works in copyright were used to train a model like GPT-3. They say maybe not, but I just can’t see how they couldn’t have included some in there.

Given that we’re authors and we make money from books by licensing copyright, how do you think this should work in an age of AI?

Arthur: That’s a whole can of worms. In art, it’s easy if the art is produced by a human and the human owns the copyright to it. But in AI, the situation is more complicated because you have chain of ownership, who owns the algorithm, who owns the data, who did the programming, who owns the machine, how close is the output to the input. This will not be resolved until machines have emotions and consciousness, and so will be artists in their own right.

Now in this sort of discussion, I’m always reminded of the Mozart story in which Mozart’s father taught the son the rules of composition, but we don’t attribute the son’s music to the father. And this I think is good to bear in mind when you talk about the relationship between the programmer and the machine.

DeepDream, for example, there is creativity on both ends. The person who invented it did a very creative job in programming and the machine became creative on its own two legs, so to speak.

In an ideal world, people training NLP (Natural Language Processing) using text from art that we’ve produced, well, we should be paid for it. But, people should also pay you when they photocopy your work and that’s hardly ever done. Although we have ownership of our writings, it’s out there in the world. It can be scanned and then put into someone else’s text, and then with some word changes, it would just disappear under the radar. There’s really not much legal recourse unless you have a lot of money, or it’s just a blatant theft of paragraphs or pages from your work, or from the papers that you write.

Now perhaps somewhat in the future, we’ll come up with some sort of DNA markers that will mark our work and set off an alarm if something terrible is happening to it.

Copyright in the age of AI is an active discussion because the line is being blurred between machine and human.

Incidentally, as you probably know, cyber lawyers still refuse to agree that machines can be creative. And this 65 years after the first case of this thought, when a scientist at Bell Labs tried to get a copyright on one of the early works of AI art.

The patent clerk at the Library of Congress in Washington refused, saying that machines are just number crunchers, they cannot be creative. Then the scientist reminded the copy lawyer that he wrote the program for the machine and, therefore, there was a human hand behind it. So the patent clerk finally agreed.

Joanna: A few things there. You talked to, obviously, the child of the father is a separate entity. In my mind, that could be a line in the sand where you’re saying, basically, AI, once it can write a novel just by clicking a button, that copyright could belong to the AI.

But until then, I will be co-creating with it as the primary person in the relationship, so, therefore, I can have my name on the cover and it doesn’t need to say ‘with GPT-3,’ which I think makes sense.

And it’s interesting, last year, there was a copyright granted to an AI writer in China [Venture Beat, Jan 2020]. So that was the first, as far as I know, the first time copyright has been granted, but then you could say while it’s been granted to the company that owns the AI writer, which I think is Tencent or something like that. So as you say, we don’t know yet, which is really interesting.

Arthur: Microsoft who makes all the writing programs, does not demand that they’d be co-writer with everything you write.

Essentially, we’re machines too. We’re not born with a tabula rasa. There’s knowledge, a native knowledge that we’re born with and then we accumulate algorithms as we move along and make mental models of the world. And information is fed into us and we respond to that information with the algorithms that we have, just like machines do.

Joanna: Absolutely. I’m very much with you. The book is very positive and you say a whole new future is opening up before us, not one to fear, but one to look forward to with anticipation. What I find in the, again back in the writing community, is that there is a fear of robots taking our jobs and that type of thing. What can you say to people listening who are really afraid of this possibility?

Arthur: That fear is well-founded. There will be a lot of jobs lost to robots, to machines.

I don’t think there’s any reason to fear machines taking our creativity from us.

We don’t have to use machines. You can use a pencil and a paper, too. Or you can ‘collaborate’ with machines.

You really can’t predict more than five years into the future these days. The world is moving very quickly. What the world would be like a hundred years from now, what it is to be a human being will have been drastically, drastically, drastically transformed since we are merging with machines.

And at that point, there will be us working with machines. We’ll have enough equipment in our head, chips in our head, and so on. The line will be blurring and blurring and blurring. And then there will be machines working on their own.

So our creativity will be bootstrapped by machines, but machines have the potential for unlimited creativity.

We don’t because our brains cannot be bigger than our heads. We can have chips put in. We could think along those lines, which just generally our brain cannot be bigger than our heads while a machine’s brain can be of unlimited extent and can have unlimited amounts of information in it.

We’ll have ourselves, humans, whatever notion of a human being will be, 100 or 200 years, with a highly enhanced creativity. And then we will have machines working alone by themselves producing novels, producing artwork.

It’s one thing to say, can machines be creative? But an interesting question is also, can we learn to appreciate art, literature, and music that we know has been created by a machine?

Joanna: I agree with you. I think that’s the art side. In your book, you specifically mentioned a guy who has published something like 200,000 print-on-demand books using his algorithm scraper. And for many of my listeners, one of the biggest issues we have selling on the Amazon Kindle store is how many other books there are out there.

I totally agree about art. What is probably more of a concern to people is, well, how do we stop, something like a Chinese AI translation engine just translating the whole corpus of Chinese work into English and dumping it on the Kindle store with AI? I agree with art, but there might be problems with the commercial aspect.

Arthur: Certainly. You can’t prevent that from happening. Right now, translation is an issue and it’s not very good. It’s okay for translating simple sentences on Google Translator, but I’m sure you’ve seen instances where poetry, German poetry, is put in, what comes out in English is really weird. That’s because, again, machines at present do not have emotions or consciousness. They cannot at present be fluent in a language with all its nuances and tropes.

But sometime in the future, they will and certainly translations will be dumped on Kindle or whatever, if Kindle will be by that time. But that’s all right. We’ll be producing our work, too.

Joanna: I think that’s the focus.

Don’t look sideways, just get on with creating your own art.

I’m finding it really fun and interesting to…it’s difficult not to use the word ‘mind,’ but co-create with something that comes up with completely different stuff to my brain and that actually makes it quite fun.

What are you excited about in terms of any developments that have happened since the book that you’re seeing coming?

Arthur: Let me just go back and say why I wrote the book. I wrote the book to look at the cultural side of AI which a lot of people in AI actually don’t look at. I meant the book to be upbeat in that there are too many dystopian scenarios out there in pop books and in newspapers as well.

But as I said before, you can’t predict more than five years in the future. So to say that a hundred years from now robots will be running after us and attempting to eat us or whatever, turning us into household pets, well, we don’t know that that will happen at that point.

Right now, the biggest danger of AI is lack of it because AI has become essential for healthcare, climate control, and right now is playing a big role in medical research in, for example, protein folding and also investigating the structure of viruses in order to better understand and deal with COVID.

I’m excited about machines producing art, literature, and music of the sort that we presently cannot imagine.

And this will perhaps happen, and this will definitely happen in the not too distant future when machines will have emotions and consciousness, as I’ve said so many times. We’ll be able to communicate with those machines and they will be the brains of robots.

And so at that point, we will need a new code of ethics for robots. At any rate, at that point, except copyright issues, machines will have their own art, literature, and music.

Now when I began my book, I knew a lot about AI-created art and music, but not much about AI-created literature. And I feared actually that there would not be enough to fill up a chapter. How wrong I was.

AI-created literature, including humor, is indeed considered to be the final frontier since it concerns so many intelligences. Now one amazing development that has emerged since my book was published, since I finished writing the manuscript, is GPT-3 which we’ve said something about before.

What I find amazing about it is that, well, we know that images, music, musical notation, and words can be encoded in numbers, and numbers are the grist for artificial neural network machines. GPT-3 is an artificial neural network machine and at the level of numbers, in pixels. Words and musical notation are all the same.

There’s a democracy down there amongst numbers. And so what I’m excited about is something, some GPT-3, 10, 11, 12, 13 will be able to take these numbers and sculpt words, sculpt musical notations, and perhaps produce a symphony from Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

In other words, AI is opening up whole new worlds.

Joanna: So you mean cross-collaborative art? Taking the pixels of a painting, for example, and turning that into words or music?

Arthur: Right. Whenever there will be a unity among the arts, which is what the Greeks alluded to. There’ll be unity among the arts and that unity will be found in numbers.

Joanna: I love that idea. I’m not musical. I’m words. But I love the idea of turning words into music without having something in the middle that would do that. That sounds awesome.

Arthur: Well, that’s being done already actually, but not at the level of GPT-3. That’s being done by looking at the emotive content of words. I discussed that in my book, as a matter of fact. But what I’m talking about is sculpting with words. I can’t even imagine that, sculpting with musical notes.

Joanna: That’s interesting. I actually was at WIRED LIVE last year, or the year before, in-person, and they had a musical guy on stage who was collaborating, he was riffing musically and the AI was creating a digital sculpture, a digital kind of 3D sculpture on an output screen related, as you say, to the emotion that the music was creating.

All this stuff is very cool and as you say it’s about expanding our creativity beyond what we can do alone. So in that way, it is true collaboration.

Arthur: Yes. That is the thing to keep in mind. You said it exactly. We’re looking at machines to expand our creativity, to expand our life, to expand how we understand our world and universe as well.

Joanna: You talked about us merging with the machines, what do you think about Elon Musk’s Neuralink project where basically — they’ve tested it in a pig now, I think — where filaments that are embedded in your brain?

What do you think about Elon Musk’s Neuralink project?

Arthur: Neural laces. I think that’s a great idea where it can be at one with everyone else. You never forget a face. You never lose your train of thought. And you never forget a name. I think that’s great.

That is a step in the future. To actually do that on a person will be quite something, but we’re already at the point where chips are being inserted into our heads, damaged parts of brains can be taken care of by inserting the correct combination of chips.

Certain parts of the brain have certain algorithms associated with them and they can, of course, be instantiated into a chip and then inserted into your brain. And that will, of course, prolong our life expectancy which I think is a great idea.

Joanna: It is a very interesting time to be alive, that’s for sure!

Arthur: Absolutely.

Joanna: Well, that’s fantastic.

Where can people find you and your books online?

Arthur: The book’s website is artistinthemachine.net. My personal website is arthurimiller.com and I’m on Twitter at @ArthurIMiller. That’s where you can find me.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, thanks so much for your time, Arthur. That was great.

Arthur: Thank you very much, Joanna. It’s been a pleasure.

The post The Artist In The Machine: The World Of AI-Powered Creativity With Arthur I. Miller first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn