What are some of the common mistakes you see in the submission process?

STEINBERG: Don’t say, “If you don’t like this novel, I have many other I could show you.” Don’t say, “This will make a great movie, too.” Don’t do that fake thing where you pretend you know all about the stuff I’ve agented. It’s funny because I think that’s a piece of advice that writers always gets—research the agent and talk about the other work they’ve sold. But it always comes off as very false to me unless you’ve really read something I’ve sold. And I don’t want you to waste your time reading something of mine just to write a query letter.

STEIN: I would say to go the other way around. Write to agents whose books you’re actually in love with.

STEINBERG: But what if those agents pass and you still want an agent?

STEIN: Then you should read more books. [Laughter.]

What else?

STEINBERG: Don’t talk about a character sweating on the first page or two.

RUTMAN: Sweating?

STEINBERG: Yeah. It happens all the time. The writer’s like, “He was sweating profusely….” It’s supposed to denote tension, I think.

RUTMAN: Also don’t write the phrase “sweating profusely.”

STEINBERG: I have a joke in my office where if a character is sweating in the first two pages, I go, “Sweating!” [Laughter.] Also, people are always “clutching” steering wheels in the first few pages.

STEIN: That’s the cliché thing.

STEINBERG: And don’t wake up from a dream on the first page. No dreams on the first page.

STEIN: It’s best to avoid dreams if possible.

But this is all craft stuff. Let’s go back to the submission process.

STEIN: Don’t write “Because of your interest in international fiction…” or whatever you think the agent’s interest is. That means you’ve been trolling some Web site, and that freaks me out. Don’t let me see that you’ve been trolling some Web site that says I like a certain kind of genre. If you know who I am, you should know who I am because you’ve done some kind of research that has to do with the specific books I represent. That should only be because you’ve fallen in love with one or two of those books. And that’s pretty unlikely because those books haven’t sold very many copies. So you probably shouldn’t be writing to me to begin with. [Laughter.]

RUTMAN: “Just avoid me altogether. I haven’t helped any of these people, really, and I’m not going to help you.”

STEIN: Exactly. There shouldn’t really be anybody writing to me at all.

STEINBERG: That’s off the record, right? Can I say “Off the record” on your behalf?

STEIN: What can I say? I’m funny.

STEINBERG: And of course with the e-mail submissions, don’t cc a hundred agents and say, “Dear Agent….”

STEIN: I got an e-mail query addressed to “Elizabeth” today.

MASSIE: I get those. Those are an instant delete.

STEIN: They are.

RUTMAN: Don’t try to write eye-catching cover letters. It just isn’t really going to enhance my anticipation going into the manuscript.

On the flip side of that, what do you want them to do? I think it can seem really hard to get an agent’s attention when you live in a small town somewhere and you don’t know anybody.

STEINBERG: Well, know somebody. [Laughter.] I’m serious. We’re in the age of e-mail and the Internet. If you e-mail twenty of your friends and say, “Do you know anyone in publishing?” someone has to know somebody. Or somebody who knows somebody. You know what I mean? Find how you know somebody.

STEIN: But you know what? I’ve actually taken on several clients who didn’t know anybody in publishing. I’ll give you an example: Anya Ulinich, who’s done pretty well for somebody who didn’t know anybody. She did some research and asked herself, “Okay, I’m Russian, and my novel has something to do with Russia, so who represents Russian novels?” She did some research and targeted those agents and wrote a query letter that was just really straightforward. It was like, “Here’s my deal. Here’s why I’m writing to you.” It was completely unpretentious and completely straightforward and well written, and because of all that and because there was nothing in it that made me think, “Oh, she’s read some book that tells you how to write query letters”—it was just very natural—I asked to see pages. I don’t think you have to know somebody.

STEINBERG: But it is one way of getting an agent’s attention. I have a lot of clients who didn’t know anyone either. But it is a good way to do it. Because when I get a query from a friend of a friend, it definitely goes in a different pile. I would also say to follow what the agent’s Web site says. If it says, “Send the first twenty-five pages,” do that. And don’t send the thirty-third chapter of your novel. Send the first chapter.

MASSIE: And don’t try too hard. Sometimes I get these queries that describe the book as a cross between this best-seller and that best-seller and ten different other things. I always find that really distracting and unhelpful.

STEIN: And don’t compare the book only to movies.

RUTMAN: I feel like people have generally read something that tells them how to write, at the very least, an unobjectionable cover letter. I like it when they are fairly matter-of-fact. To me that suggests, whether it’s well placed or not, a certain confidence that you’re going to appreciate the pages rather than the letter. I don’t have any sort of pointed advice about what people ought to do in a cover letter. It just doesn’t matter that much. It’s going to get read.

By your assistant. Just to play devil’s advocate.

RUTMAN: Some of it, yes. But she has excellent taste. And if you’re working with someone whose taste you really value and trust, they bring you the things you probably would have plucked out yourself.

MASSIE: And she’s looking for certain things. Has the writer been published before? What are their credits?

RUTMAN: I think if anybody reads a certain number of cover letters they start to sense what is nice to have in a cover letter. But people generally seem to know. And if you’ve already published things, it suggests that you’ve been willing to subject yourself to some of the cruelties of the process and that you realize it’s probably part of the deal.

STEIN: That’s the thing. It’s possible to get published in some good literary magazines without an agent. Very possible. In fact, in some places it’s easier. And if you’re writing fiction, and especially if you have the misfortune of being a short story writer, then you should spend a lot of time and energy getting published in those places before you start looking for an agent. Because it’ll make everybody’s job so much easier.

Does anybody have a success story about finding a writer in a literary magazine?

STEINBERG: I read a great short story in the Southern Review a few years ago and called the writer and eventually sold the novel-in-stories to Ann Patty at Harcourt, who’s great and who unfortunately is no longer at Harcourt. It was called The Circus in Winter by Cathy Day. It’s funny because I originally looked at the story because I liked the author’s last name. I don’t know if that means I’m superficial, but at the time I was interested in writers whose last names were words, and her last name was Day, so—

RUTMAN: This was a phase you went through?

STEINBERG: It was! I also went through a phase of looking for names with alliteration.

STEIN: Note to readers.

STEINBERG: For example, I represent a guy named Brad Barkley.

STEIN: What’s your phase right now? What are you into?

STEINBERG: Now I’m in the supporting-my-three-children phase.

How’s that going?

STEINBERG: It’s going okay. [Laughter.]

How do you guys feel about short stories?

STEIN: If they’re awesome, they’re awesome. Even if we can’t sell them, they’re still awesome.

MASSIE: I’m with Anna. I love short stories.

And can you sell them?

MASSIE: On occasion. It’s hard. It always helps if there’s a novel coming. But if you’ve got a great short story collection, it will stand out. I represent a writer who was referred to me by an editor at a literary magazine. I read it and it blew me away. I sold it, it was published, it got great reviews, but it did not sell very many copies. But then the writer, Robin Romm, went on to write an amazing memoir that was just reviewed on the cover of the New York Times Book Review. She’s a fantastic writer and you never know where a short story writer is going to go or what stories they have left to tell. So, you know, she wasn’t making a lot of money in the beginning, but she’s going to have an amazing career.

STEIN: And here’s another thing. A short story writer might end up just being a short story writer, which might be our nightmare, but what if he ends up being one of those—

MASSIE: Alice Munro or somebody.

RUTMAN: We don’t really have much choice but to represent talent in whatever form it happens to come. And if it happens to come first in short story collection form, that does not make things easier, practically speaking, but it’s not in itself a reason not to do it. The climate hardly encourages it, and it’s not fun to call an editor and say, “What I have for you now—brace yourself—is a collection of short stories.” I mean, that’s like a meta-joke, I suppose, at this point. But you shouldn’t just abandon it. You know it’s going to be hard so you ask yourself, “How fired up am I about trying this?” With a story collection, that question is a good test of how intrinsically great you find it.

STEIN: It had better be super-duper-duper-duper good.

RUTMAN: Right. One of my colleagues gave me a collection not that long ago. It was sort of short, and the author had not really tried to publish any of them, and I took it home, sort of unhappily, and I ended up being like, “Oh. Okay. So this is a person who can do this.” If you feel that way as an agent, what are you going to do, say no? It just doesn’t really feel like a smart option.

STEIN: But novels are beginning to feel that way too. I mean, really—it’s like the novel is the new short story.

RUTMAN: The short story is the new poem…

STEIN: Yeah, the short story is the new poem, novels are the new short story…. It’s hard out there.

RUTMAN: If you’re talking to a certain audience, say an MFA audience, you hear the sentiment of, “Ugh, if only I could get past the short story collection and get on to the novel, easy street can’t be far behind.”

STEIN: There is no easy street.

RUTMAN: Exactly. It doesn’t exist. But there is this unhelpful assumption that you just need to get to a novel, at which point your publishing fortunes will brighten.

STEINBERG: There are probably only a hundred people in the United States who make a living off novel writing.

STEIN: Did you make that number up?

STEINBERG: Yeah, I just made it up.

STEIN: I think that’s a really great point and that number sounds about right to me.

STEINBERG: I think all of my clients have day jobs. Writing is just not going to be a way to stop doing what you’re doing for a living, probably. And I wouldn’t advise it. I have clients who sometimes sell their books for a decent amount of money and are like, “Ooh, should I quit my job?” And I panic and say, “No!” It also affects your work because you start writing for the marketplace too much.

STEIN: And the money is never what the money looks like.

STEINBERG: Exactly. The money has to be gravy and not a base salary.

MASSIE: And you never know what the second book will do, versus the first one, and what the advance for the next book is going to look like.

You are all deep inside this world, but so many writers aren’t. If you were a beginning writer who lived out in Wisconsin or somewhere and didn’t know anybody and you were looking for an agent, how would you do it?

STEINBERG: I would not worry about looking for an agent. I would work on my writing for a long time. And then when I was finally ready, I would ask everyone I know what they thought I should do.

MASSIE: I agree with that. I would concentrate on getting published in well-regarded literary magazines and, chances are, agents will come to you.

RUTMAN: I wouldn’t relish the prospect of looking for an agent if I had not come through a program, where a professor can often steer you in some helpful direction. I guess you’d start at the bookstore.

MASSIE: You pick up your favorite books and look at the acknowledgments and see who represented them and write those people a letter.

STEIN: I’m with Peter. I wouldn’t worry so much about finding an agent. The thing is, there aren’t that many great writers. Right? And there seem to be a lot of people trying to write novels and find agents. If you’re looking for an agent, it means you want to sell your book. But if there are only a hundred people making money as writers—and I think that number sounds about right—and you’re trying to sell your book to make money, then that doesn’t really make sense. It’s like playing the lottery. If I thought I’d written something brilliant, I would hope that, like Peter said, I would be continuing to work on my writing.

RUTMAN: But don’t you think most people who are working on their writing feel kind of persuaded that they are brilliant and have something really unique and wonderful to say?

STEIN: I also think they feel this pressure to get published. With all the MFA programs, and with all the writing conferences and programs that they pay money for, there’s this encouragement to get published.

RUTMAN: Sure. It’s the stated goal.

STEIN: Right. That’s the goal. But for 99 percent of people writing fiction, that shouldn’t necessarily be the goal. Maybe writing should be the thing they work on for many years and then maybe they should think about getting published.

RUTMAN: I think being published has come to feel, for reasons I can’t explain, too achievable. To take a step back, I think the idea of writing a book has come to seem too achievable. I don’t know what to attribute that to. It may be the fact that famous people have access to people who can write a tolerable book for them, which might create the impression that most of us should be thinking about writing a book. I think it used to feel rightfully daunting to write a book. People should be daunted by the prospect of writing a book—and more than they may be at the moment. I’m not saying that writing can’t be a hobby. But professionalizing it? That’s a whole other step, and you then expose yourself to a whole other set of challenges and disappointments that you have to take into consideration. But at some point I feel like there was some kind of fundamental shift that made writing a book—and finishing it and publishing it—seem like not that big a deal. Or not a big enough deal.

STEINBERG: One thing we should convey is how rare it is that a great piece of fiction crosses our desks from someone new.

ALL: Yes.

STEINBERG: It happens maybe, what, once a year? Twice a year? That’s it. It’s so rare. So for people in Wisconsin who might be reading this and trying to figure out how to get published, they should keep that in mind. That’s why stressing the work is so important—because it’s so rare that something extraordinary crosses our desks. I like to think that all of our instincts are good enough, and we’re well trained enough, and we’ve done this long enough, to recognize it when it arrives. But that aspect of it can’t be stressed enough, which is why I say to work on it for a long time. You also only get one shot with an agent. There are no do-overs. When we get letters that say, “I know you passed on this six months ago but I’ve rewritten it,” it’s difficult to look at it again. You really do only get one shot.

Do you guys feel competitive with other agents?

RUTMAN: I’m not sure I feel that competitive. I’m definitely envious of other agents. [Laughter.] But that’s not the same thing.

STEIN: I know Jim’s not competitive because we were competing for a client once and both of us are so uncompetitive that he was like, “No, no, Anna’s so great,” and I was like, “No, no, Jim’s so great.”

Who won?

STEIN: Jim.

RUTMAN: Competitive just feels like the wrong word. I can apply competitiveness to all kinds of other arenas but I have trouble, for some reason, doing it here. Because even competing for a client feels…I mean, maybe if I was a huge rock star I would just sit back and point at my shelf and say, “That’s why you should be represented by me.” When that’s not really an option it becomes a charm expedition. You’re trying to persuade somebody that you care enough, or that you see enough in what they’ve done, to suggest to them that you would be the right person for the job.

Tell me a little about how you view your jobs. How do you think about your obligations and responsibilities to your clients?

RUTMAN: The responsibilities are so amorphous and encompassing that it’s hard to sum up. I’ve never done it very successfully. I guess the boundaries are fairly few. You’re trying to find books that you believe in and feel like you’d be doing the author and yourself a favor by involving yourself with, and then you’re advising them about its readiness to be exposed to these calculating strangers, and then you choose the strangers you’re going to share it with, and then, if you’re lucky enough to have options among those strangers, you’re telling them which one is best. And then the book gets published and the landscape changes to a whole new level of abstraction about what constitutes a good publication experience and what doesn’t. And how many people wind up being published without feeling aggrieved or getting less than what they could have from the experience? A lot of people are disappointed by it. It’s a pretty boundary-less relationship. It extends into all kinds of areas that are personal, that involve editorial work, that involve…. The editorial part’s nice because at least it’s a place to stop. It’s also, for my money, the most interesting part of the process. You’re talking about something that, presumably, has moved you enough to want to think and discuss.

STEIN: It sounds so cheesy to say, and everyone will agree with it, but the job is about finding books that you feel should exist in the world, and should for a long time. I mean, this summer I read Anna Karenina, and it made it impossible for me to even think about taking on a book for months. It’s really important for us to read published books that we don’t represent while we’re reading our own clients’ books. It’s important for us to stay current, but also to read classics. And it reminded me of why I really do what I do. It’s because I want the books I represent to be important, and for a long time. I don’t want to sell a book just to sell a book. I want each one to matter. I mean, that’s a little heavy, and none of your books is ever going to be Anna Karenina—Anna Karenina is Anna Karenina, let’s not touch it—but that’s the idea.

RUTMAN: That’s why the job is interesting. There is always the chance, no matter how remote, that that could happen. It won’t necessarily be Anna Karenina, but you can find something that you didn’t expect, and you can glimpse stuff in it that you couldn’t anticipate, and the writer can change the way you think about something. That is, in a job, a pretty interesting thing, even if it remains largely in the realm of possibility. It’s still a nice possibility to encounter on a daily basis. I mean, that’s better than most jobs I’ve been able to conceive of as possibilities for myself.

MASSIE: It’s terrific. It means that you learn something every day. You pick something up and you don’t know what world it’s going to take you to or what it will teach you, and that’s an incredible thing. I think that’s one of the wonderful things about what we do. If you find something that you’re blown away by, you actually can help get it to a larger audience. It’s amazing when people will say to you, “I read that book you represented. God, that was amazing. It really affected me.” That’s a great feeling.

How about your responsibilities?

MASSIE: I sometimes feel like a cross between a mother, a shrink, an accountant, a lawyer…. You wear so many different hats on a daily basis. You’re juggling so many things, and the clients are so different. They all have different personalities and one person needs handholding or reassurance after every rejection letter and others just want to hear from you when there’s news. It’s different with everybody. I haven’t ever seen myself as doing one thing. I mean, with one client you’re going over royalty statements and with another you’re hearing about her marriage or some trauma she’s going through. It’s a pretty intimate relationship.

STEINBERG: It’s a friendship.

MASSIE: It’s a relationship. You have your ups and downs, and the good and the bad, and it’s the mark of a really great relationship with an author that you can weather the storms and get through the good publications and the bad publications, the good reviews and the bad reviews.

RUTMAN: We’re like disappointment brokers.

STEIN: That’s why trust is so important.

MASSIE: Trust is key.

STEIN: That’s why, from the very beginning of the relationship, the more up-front you are, the better. The way you approach an agent says so much about your personality and your character. So if you’re very straightforward in your query letter and cover letter, that shows us something. And if we’re going to have a long-term and trusting relationship, that’s important. Let’s say you have several agents interested in you. Let’s say you go with one agent and you don’t tell the other agents, or you’re somehow a little dishonest about the process. Things might not work out with that agent—that agent might move to Wisconsin for some reason and decide to leave publishing—and you’re going to have to face those other agents. It’s just really important to have integrity and to be honest and to be gracious from the very beginning.

STEINBERG: I think we’ve all done this long enough that we can sort of suss out when someone’s being false or fake or dishonest. So you really shouldn’t even try.

RUTMAN: Because if you start to get the sense, early enough in the process, that someone seems like trouble, those suspicions are rarely misleading or without some kind of foundation. One time I was in the rare position of dealing with a writer who was wildly and indisputably talented but came with some warning signs. Actually they weren’t warning signs so much as actual warnings from people who knew the writer and said, “I’ll be up-front with you. This writer is remarkable in the most important ways and a challenge in a great many other ways.”

STEIN: “Totally insane” is what they probably said.

RUTMAN: Yeah, that’s what they meant. So what do you do? Is it a measure of how heroic an agent you are if you take them on? Is it a good idea? I’m not so sure that it is.

STEIN: I tried that once. I took on somebody who was insanely talented but also insane. And I tried to be heroic. I tried my very, very best. And it ended, not only in tears, but in legal fees. I made a New Year’s resolution: No more. No more crazy ones, ever again.

STEINBERG: It’s not worth it. Life’s too short.

MASSIE: There are also the clients who are blamers. They’re always looking for somebody to blame. They’re like, “That person didn’t do this” or “You didn’t do that.”

STEIN: Those are agent-jumpers.

MASSIE: Exactly.

STEINBERG: That’s another reason why writers should make sure it’s the right match. You don’t want to switch agents unless you have to. If you have to tell an agent, “Oh, I’ve had two agents and it hasn’t worked out,” the new agent will perceive that as a warning sign. Unless it’s legitimate. Sometimes things don’t work out or the personalities just aren’t right.

STEIN: But in general, everybody wants the relationship to work. I mean, we’re all pretty young and we’re not naïve, but we are a little bit romantic or otherwise we wouldn’t be in this industry—obviously there’s no money in it. We go into the relationship thinking, “We want to grow old together.” It’s a real relationship. It’s like a marriage. We want to grow old together. So if it doesn’t work out it’s usually for pretty serious reasons.

STEINBERG: My clients and I talk about growing old together. We sort of joke about it. “When we’re old we’ll do this or that.”

MASSIE: Right. It always worries me when you’re talking to a writer about representing them and they ask, “So, do you work on a book-by-book basis?” I’m like, “No. I do not work on a book-by-book basis.” I’m not interested in working on a book-by-book basis. For me it’s a long-term relationship.

STEINBERG: That’s one of the reasons why you take on short story writers. You see the relationship in a long-term way—you’re trying to see the forty-year arc. And when you work with storytelling so much, one thing you learn is that there’s a story arc to the client-agent relationship, too. You have an arc of a story in the way that your relationship develops.

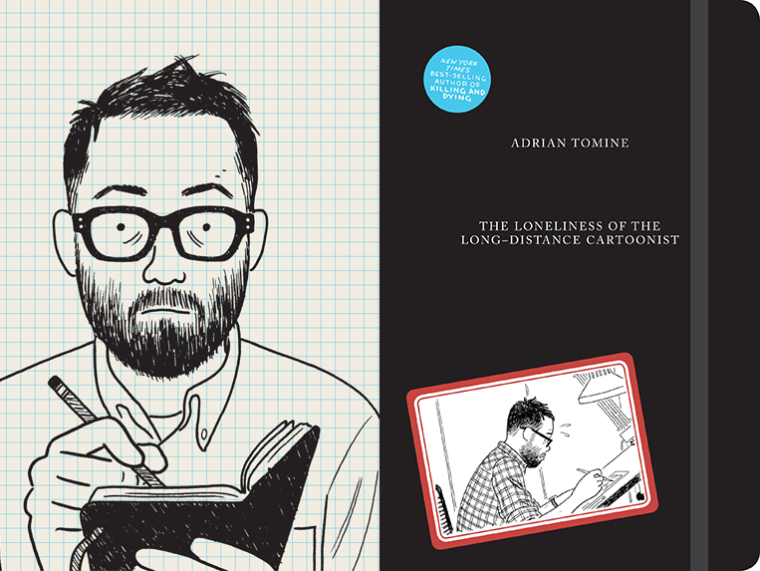

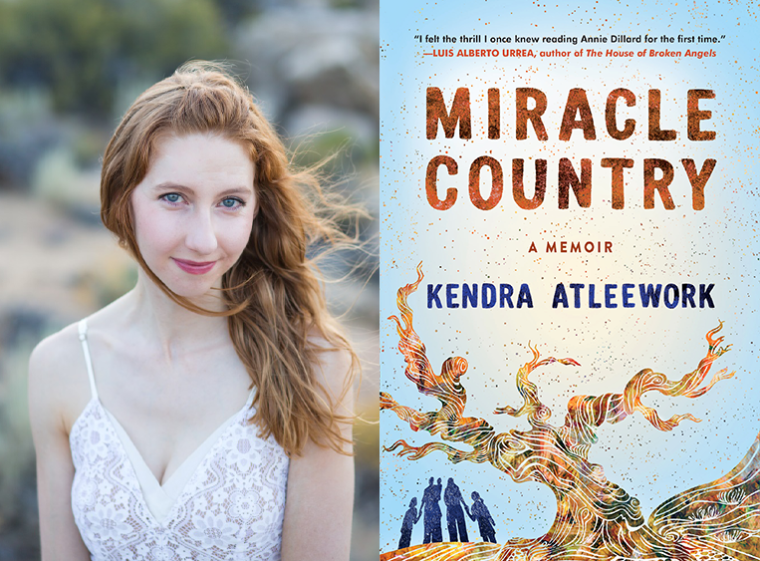

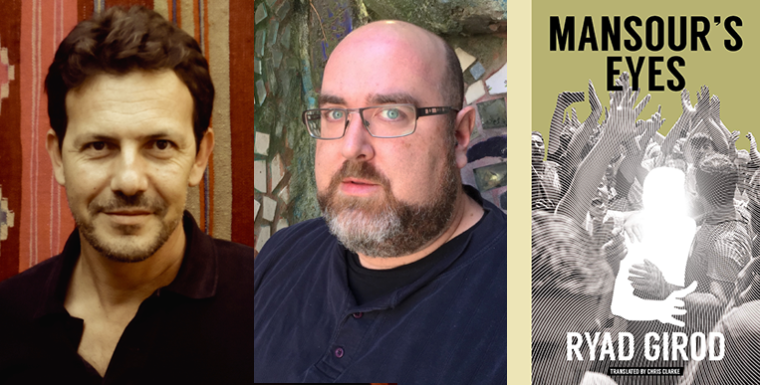

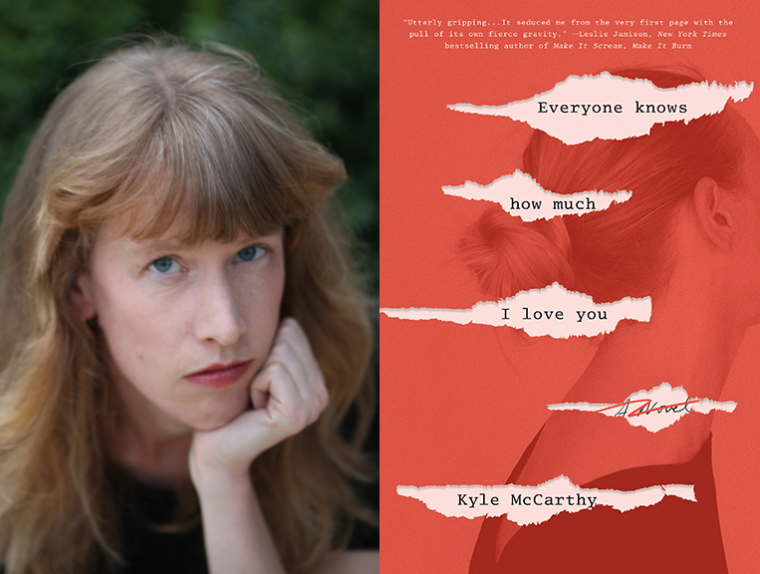

Areas of interest: Literary fiction, narrative nonfiction, journalism/investigative reporting, memoir, pop culture, graphic novels

Areas of interest: Literary fiction, narrative nonfiction, journalism/investigative reporting, memoir, pop culture, graphic novels