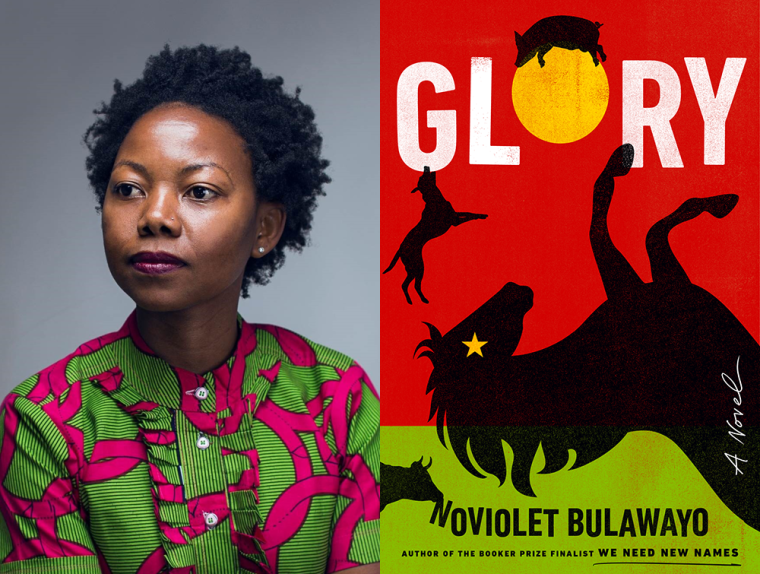

For our thirteenth annual roundup of the summer’s best debut fiction, we asked five established authors to introduce this year’s group of debut writers. Read the July/August 2013 issue of the magazine for interviews between Paul Harding and NoViolet Bulawayo, Karen Russell and Bushra Rehman, Nathan Englander and Bill Cheng, Curtis Sittenfeld and Anton DiSclafani, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Chinelo Okparanta. But first, check out these exclusive excerpts from the debut novels and story collections.

We Need New Names (Reagan Arthur Books, September) by NoViolet Bulawayo

Corona (Sibling Rivalry Press, August) by Bushra Rehman

Southern Cross the Dog (HarperCollins, May) by Bill Cheng

The Yonahlossee Riding Camp for Girls (Riverhead Books, June) by Anton DiSclafani

Happiness, Like Water (Mariner Books, August) by Chinelo Okparanta

We Need New Names

By NoViolet Bulawayo

“Hitting Budapest”

We are on our way to Budapest: Bastard and Chipo and Godknows and Sbho and Stina and me. We are going even though we are not allowed to cross Mzilikazi Road, even though Bastard is supposed to be watching his little sister Fraction, even though Mother would kill me dead if she found out; we are just going. There are guavas to steal in Budapest, and right now I’d rather die for guavas. We didn’t eat this morning and my stomach feels like somebody just took a shovel and dug everything out.

Getting out of Paradise is not so hard since the mothers are busy with hair and talk, which is the only thing they ever do. They just glance at us when we file past the shacks and then look away. We don’t have to worry about the men under the jacaranda either since their eyes never lift from the draughts. It’s only the little kids who see us and try to follow, but Bastard just wallops the naked one at the front with a fist on his big head and they all turn back.

When we hit the bush we are already flying, scream-singing like the wheels in our voices will make us go faster. Sbho leads: Who discovered the way to India? and the rest of us rejoin, Vasco da Gama! Vasco da Gama! Vasco da Gama! Bastard is at the front because he won country-game today and he thinks that makes him our president or something, and then myself and Godknows, Stina, Sbho, and finally Chipo, who used to outrun everybody in all of Paradise but not anymore because somebody made her pregnant.

After crossing Mzilikazi we cut through another bush, zip right along Hope Street for a while before we cruise past the big stadium with the glimmering benches we’ll never sit on, and finally we hit Budapest. We have to stop once, though, for Chipo to sit down because of her stomach; sometimes when it gets painful she has to rest it.

When is she going to have the baby anyway? Bastard says. Bastard doesn’t like it when we have to stop doing things because of Chipo’s stomach. He even tried to get us not to play with her altogether.

She’ll have it one day, I say, speaking for Chipo because she doesn’t talk anymore. She is not mute-mute; it’s just that when her stomach started showing, she stopped talking. But she still plays with us and does everything else, and if she really, really needs to say something she’ll use her hands.

What’s one day? On Thursday? Tomorrow? Next week?

Can’t you see her stomach is still small? The baby has to grow.

A baby grows outside of the stomach, not inside. That’s the whole reason they are born. So they grow into adults.

Well, it’s not time yet. That’s why it’s still in a stomach.

Is it a boy or girl?

It’s a boy. The first baby is supposed to be a boy.

But you’re a girl, big head, and you’re a first-born.

I said supposed, didn’t I?

Just shut your kaka mouth, you, it’s not even your stomach.

I think it’s a girl. I put my hands on it all the time and I’ve never felt it kick, not even once.

Yes, boys kick and punch and butt their heads. That’s all they are good at.

Does she want a boy?

No. Yes. Maybe. I don’t know.

Where exactly does a baby come out of?

The same place it goes into the stomach.

How exactly does it get into the stomach?

First, Jesus’s mother has to put it in there.

No, not Jesus’s mother. A man has to put it in there, my cousin Musa told me. Well, she was really telling Enia, and I was there so I heard.

Then who put it inside her?

How can we know if she won’t say?

Who put it in there, Chipo? Tell us, we won’t tell.

Chipo looks at the sky. There’s a tear in her one eye, but it’s only a small one.

Then if a man put it in there, why doesn’t he take it out?

Because it’s women who give birth, you dunderhead. That’s why they have breasts to suckle the baby and everything.

But Chipo’s breasts are small. Like stones.

It doesn’t matter. They’ll grow when the baby comes. Let’s go, can we go, Chipo? I say. Chipo doesn’t reply, she just takes off, and we run after her. When we get right to the middle of Budapest we stop. This place is not like Paradise, it’s like being in a different country altogether. A nice country where people who are not like us live. But then you don’t see anything to show there are real people living here; even the air itself is empty: no delicious food cooking, no odors, no sounds. Just nothing.

Budapest is big, big houses with satellite dishes on the roofs and neat graveled yards or trimmed lawns, and the tall fences and the Dura walls and the flowers and the big trees heavy with fruit that’s waiting for us since nobody around here seems to know what to do with it. It’s the fruit that gives us courage, otherwise we wouldn’t dare be here. I keep expecting the clean streets to spit and tell us to go back where we came from.

At first we used to steal from Stina’s uncle, who now lives in Britain, but that was not stealing-stealing because it was Stina’s uncle’s tree and not a stranger’s. There’s a difference. But then we finished all the guavas in that tree so we have moved to the other houses as well. We have stolen from so many houses I cannot even count. It was Bastard who decided that we pick a street and stay on it until we have gone through all the houses. Then we go to the next street. This is so we don’t confuse where we have been with where we are going. It’s like a pattern, and Bastard says this way we can be better thieves.

Today we are starting a new street and so we are carefully scouting around. We are passing Chimurenga Street, where we’ve already harvested every guava tree, maybe like two-three weeks ago, when we see white curtains part and a face peer from a window of the cream home with the marble statue of the urinating naked boy with wings. We are standing and staring, looking to see what the face will do, when the window opens and a small, funny voice shouts for us to stop. We remain standing, not because the voice told us to stop, but because none of us has started to run, and also because the voice doesn’t sound dangerous. Music pours out of the window onto the street; it’s not kwaito, it’s not dance-hall, it’s not house, it’s not anything we know.

A tall, thin woman opens the door and comes out of the house. The first thing we see is that she is eating something. She waves as she walks towards us, and already we can tell from the woman’s thinness that we are not even going to run. We wait, so we can see what she is smiling for, or at. The woman stops by the gate; it’s locked, and she didn’t bring the keys to open it.

Jeez, I can’t stand this awful heat, and the hard earth, how do you guys ever do it? the woman asks in her not-dangerous voice. She smiles, takes a bite of the thing in her hand. A pink camera dangles from her neck. We all look at the woman’s feet peeking underneath her long skirt. They are clean and pretty feet, like a baby’s. She is wiggling her toes, purple from nail polish. I don’t remember my own feet ever looking like that; maybe when I was born.

Then there’s the woman’s red chewing mouth. I can tell from the cord thingies at the side of her neck and the way she smacks her big lips that whatever she is eating tastes really good. I look closely at her long hand, at the thing she is eating. It’s flat, and the outer part is crusty. The top is creamish and looks fluffy and soft, and there are coin-like things on it, a deep pink, the color of burn wounds. I also see sprinkles of red and green and yellow, and finally the brown bumps that look like pimples.

Chipo points at the thing and keeps jabbing at the air in a way that says What’s that? She rubs her stomach with her other hand; now that she is pregnant, Chipo is always playing with her stomach like maybe it’s a toy. The stomach is the size of a football, not too big. We keep our eyes on the woman’s mouth and wait to hear what she will say.

Oh, this? It’s a camera, the woman says, which we all know; even a stone can tell that a camera is a camera. The woman wipes her hand on her skirt, pats the camera, then aims what is left of the thing at the bin by the door, misses, and laughs to herself like a madman. She looks at us like maybe she wants us to laugh with her, but we are busy looking at the thing that flew in the air before hitting the ground like a dead bird. We have never ever seen anyone throw food away, even if it’s a thing. Chipo looks like she wants to run after it and pick it up. The woman’s twisted mouth finishes chewing, and swallows. I swallow with her, my throat tingling.

How old are you? the woman asks Chipo, looking at her stomach like she has never seen anybody pregnant.

She is eleven, Godknows replies for Chipo. We are ten, me and her, like twinses, Godknows says, meaning him and me. And Bastard is eleven and Sbho is nine, and Stina we don’t know because he has no birth certificate.

Wow, the woman says. I say wow too, wow wow wow, but I do it inside my head. It’s my first time ever hearing this word. I try to think what it means but I get tired of grinding my brains so I just give up.

And how old are you? Godknows asks her. And where are you from? I’m thinking about how Godknows has a bigmouth that will get him slapped one day.

Me? Well, I’m thirty-three, and I’m from London. This is my first time visiting my dad’s country, she says, and twists the chain on her neck. The golden head on the chain is the map of Africa.

I know London. I ate some sweets from there once. They were sweet at first, and then they just changed to sour in my mouth. Uncle Vusa sent them when he first got there but that was a long time ago. Now he never sends anything, Godknows says. He looks up at the sky like maybe he wants a plane to appear with sweets from his uncle.

But you look only fifteen, like a child, Godknows says, looking at the woman now. I am expecting her to reach out and slap him on the mouth but she merely smiles like she has not just been insulted.

Thank you, I just came off the Jesus diet, she says, sounding very pleased. I look at her like What is there to thank? I’m also thinking, What is a Jesus diet, and do you mean the real Jesus, like God’s child?

I know from everybody’s faces and silence that they think the woman is strange. She runs a hand through her hair, which is matted and looks a mess; if I lived in Budapest I would wash my whole body every day and comb my hair nicely to show I was a real person living in a real place. With her hair all wild like that, and standing on the other side of the gate with its lock and bars, the woman looks like a caged animal. I begin thinking what I would do if she actually jumped out and came after us.

Do you guys mind if I take a picture? she says. We don’t answer because we’re not used to adults asking us anything; we just look at the woman, at her fierce hair, at her skirt that sweeps the ground when she walks, at her pretty peeking feet, at her golden Africa, at her large eyes, at her smooth skin that doesn’t even have a scar to show she is a living person, at the earring in her nose, at her T-shirt that says Save Darfur.

Great, now, stand close together, the woman says.

You, the tall one, go to the back. And you, yes, you, and you, look this way, no, I mean you, with the missing teeth, look at me, like this, she says, her hands reaching out of the bars, almost touching us.

Good, good, now say cheese, say cheese, cheese, cheeeeeeeese— the woman enthuses, and everyone says cheese. Myself, I don’t really say, because I am busy trying to remember what cheese means exactly, and I cannot remember. Yesterday Mother of Bones told us the story of Dudu the bird who learned and sang a new song whose words she did not really know the meaning of and who was then caught, killed, and cooked for dinner because in the song she was actually begging people to kill and cook her.

The woman points at me, nods, and tells me to say cheeeeeese and I say it mostly because she is smiling like she knows me really well, like she even knows my mother. I say it slowly at first, and then I say, Cheese and cheese, and I’m saying cheese cheeeeese and everyone is saying cheese cheese cheese and we are all singing the word and the camera is clicking and clicking and clicking. Then Stina, who is quiet most of the time, just starts to walk away. The woman stops taking pictures and says, Hey, where are you going? But he doesn’t stop, doesn’t even turn to look at her. Then Chipo walks away after Stina, then the rest of us follow them.

We leave the woman standing there, taking pictures as we go. Then Bastard stops at the corner of Victoria and starts shouting insults at the woman, and I remember the thing, and that she threw it away without even asking us if we wanted it, and I begin shouting also, and everyone else joins in. We shout and we shout and we shout; we want to eat the thing she was eating, we want to hear our voices soar, we want our hunger to go away. The woman just looks at us puzzled, like she has never heard anybody shout, and then quickly hurries back into the house but we shout after her, shout till we smell blood in our tickling throats.

Excerpted from We Need New Names by NoViolet Bulawayo, published in May by Reagan Arthur Books. Copyright © 2013 by NoViolet Bulawayo. All rights reserved.