I am hurrying to meet a short story writer in the City Garden of Sofia, Bulgaria. It is a bright winter day, with temperatures hovering a bit above freezing. The leaves are off the trees and the fountains are shut down for the season, but eight or nine chess players sit on the benches near the Sofia City Art Gallery. They eye me, bundled in my gray winter coat, curious if I’ll pay them for the dubious pleasure of watching them beat me, but I shake my head and continue. I pass the little stone statue of a flower girl left over from communist times then mount the steps of the Neoclassical façade of the Ivan Vazov National Theater and wait. Fears about social distancing, masks, and infection rates are still weeks away. It is January in Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, and I’m excited for an introduction to some of the country’s writers.

I step down into the little plaza before the red brick facade and turn to admire the white stone columns soaring up to the marble pediment festooned with gilded statues of Apollo and his muses. Towers crowned by lead domes bookend the entrance portico to the theater, with each dome surmounted by chariots bearing the goddess Nike, who is clutching a theater mask and raising what appears to be a torch. It’s a bit tough to tell for certain, as the statues are forty meters overhead.

In the distance, beyond the roof, the snow-capped summit of Mount Vitosha towers over the city. I get distracted for a moment by a half-dozen red and white balloons that blow high over my head from some celebration in the park. The balloons float up toward the contrails of an Airbus A330 crossing in the direction of Istanbul, and when my eyes return to street level, Alexander Shpatov is walking toward me along the length of the rectangular basin of the empty fountain.

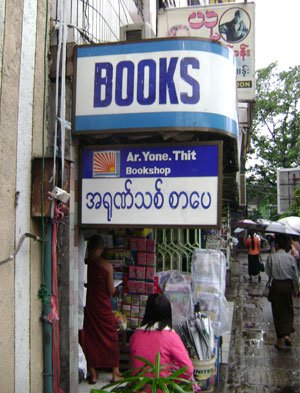

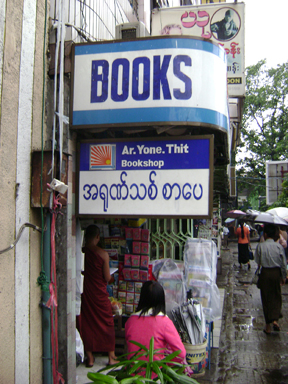

Sofia’s Ivan Vazov National Theatre (left); story writer Alexander Shpatov stands in front of a statue of Nicola Vaptsarov, a Bulgarian poet, communist, and revolutionary who died in 1942.

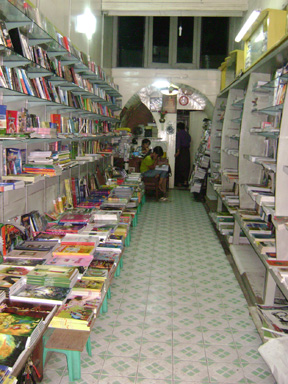

Shpatov is in his thirties, with a week-old beard and short brown hair, and dressed in a russet, knee-length duffle coat against the cold. He extends his hand and introduces himself then leads me back toward the chess players to a two-story, cylindrical, glass kiosk—about four meters in circumference—beside the art gallery. I had assumed the odd structure was closed for the winter. “It’s a library,” he explains and swings open the fogged door to introduce me to Monica Chalakova, a twenty-something, curly-haired librarian seated behind a molded-plywood desk.

The kiosk was built in the 1990s, after the fall of communism, a chaotic time in the country, Shpatov explains. It was put up by a flower seller without permission from the municipality, and the city seized it a few years later when they began to reinstitute order. The building was derelict for a time, inhabited by homeless men, then Shpatov worked with the cultural arm of city government to craft this new identity for it in 2014. The glass walls of its two stories are engraved with the letters of the Cyrillic alphabet as well as the letters of the Glagolitic alphabet, which preceded Cyrillic. (Shpatov explains that Glagolitic was invented by the seven saints of Slavic culture, who also disseminated it to the Bulgarians. In May there is a national holiday dedicated to literature, culture, and the alphabet. It is a fascinating history because the saints were professors as much as holy men. The brothers, Cyril and Methodius, taught at the Imperial University of Constantinople in the 800s and were dispatched as emissaries of the Byzantine emperor in order to persuade the imperial subjects and their trading partners to adopt Christianity. Cyril and Methodius invented an alphabet for the Slavic languages then taught it to other priests, including one named Kliment, whom the city’s oldest university is named after. The pre-Cyrillic alphabet was etched into the windows of the kiosk, together with the Cyrillic, during the building’s redesign four years ago.)

Today, the kiosk serves as a small lending library and a tourist information center. Shpatov runs literary tours in Bulgarian that depart from here during the warmer months. The city approached him to help organize the tours and the kiosk after he made a name for himself as a short story writer.

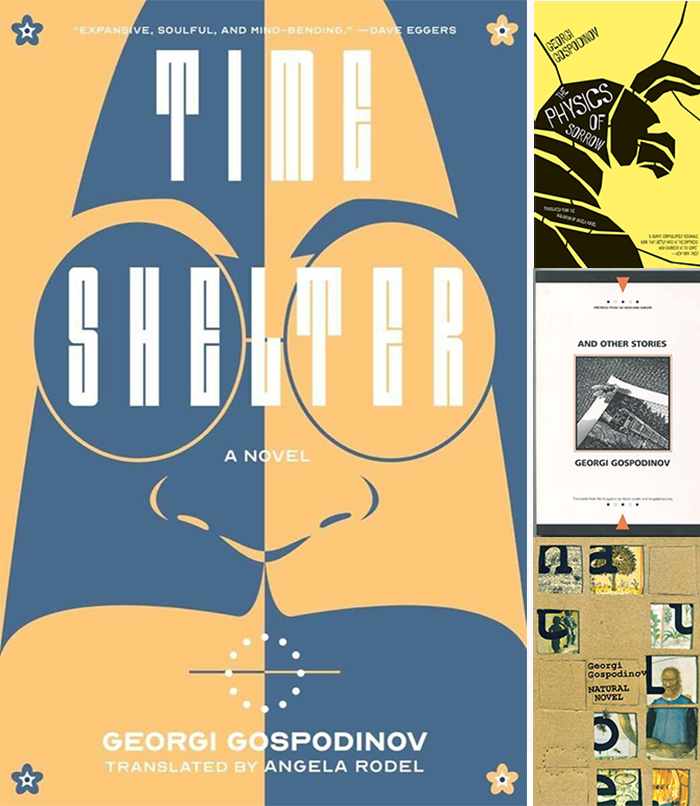

In 2006, Shpatov’s first story collection won a national award, and the three collections he has published since have all sold well and been favorably reviewed. His narratives favor urban settings, and he explains that previously, during communist times and also during the Bulgarian national revival period of the late 19th century, writers preferred to write about the villages of their births. He credits the American novelist Garth Greenwell, who taught at the American College of Sofia, where Shpatov is an alumnus, for reassuring him and encouraging him to maintain his focus on the city. The Bulgarian writer met the American writer at a reception at the school and the two became friends. “Garth asked me, ‘Why isn’t there a book about Sofia? There should be one,’” Shpatov recalls. “So I wrote one.”

His books are popular, but Shpatov tells me that on at least two occasions, when he was reading outside of the capital, a member of the audience stood, said something derogatory about “these Sofia stories,” and stormed out.

After high school Shpatov attended the University of Sofia, where he earned a law degree. He’s a lawyer by day, but writing and Bulgarian literature are clearly his passions. Today he’s agreed to lead me on a one-person literary tour.

In the warmth of the glass library, he opens a map of Sofia and explains that Sofia has six neighborhoods and more than three hundred streets named after famous poets, writers, book titles, literary characters, professors of Bulgarian literature, and literary critics. “I haven’t seen anything like this anywhere else, not even in Moscow,” he says. His finger jabs at place names on the map as he tells me about Ivan Vazov, the writer the theater is named after. In 1893, after the Russians helped the Bulgarians kick out the Ottoman Turks, who had ruled Bulgaria since the 14th century, Vazov wrote his novel Under the Yoke, about the transition from Ottoman rule. The book is canonical reading in Bulgarian public schools and is so famous that a recent re-translation that substitutes contemporary Bulgarian words and phrases for many of the antiquated words and expressions in the original has created a national debate.

Next Shpatov tells me about Geo Milev, a poet from the early part of the 20th century whose photo I’ve seen before: Milev posed for photos with a sweep of brown hair dramatically covering the right side of his face. I had assumed it was a fanciful bit of tonsorial flare, but Shpatov explains that the poet was disfigured in World War I, that he lost his right eye and had a scar and indentation across the right half of his face.

The two-story, cylindrical glass kiosk used as a lending library in the City Garden (left); a statue of Geo Milev, a Bulgarian poet, journalist, and translator.

Milev was a national hero, but he was also a political leftist during the nationalist period between the wars. After a communist group planted a bomb in 1925 that blew up the rooftop of the St. Nedelya Church in the city center, killing 200 and injuring 700 members of the ruling class, Milev was swept up in a round-up of leftists. He was never seen again. Thirty years later, during communist times, a mass grave was uncovered, and Milev’s damaged skull was identified and his glass eye was found.

Shpatov’s lessons continue as we leave the kiosk and head out into the brisk weather for a tour that lasts for another ninety minutes but never leaves the one-block radius surrounding the quiet park. He points out the plaque on a large, rough stone before the national theater that marks the spot in 1895 where the famed satirical writer, Aleko Konstantinov, met with a group of naturalists who formed one of the nation’s first hiking and tourism clubs.

Shpatov waves at the Grand Hotel of Sofia, an 11-story glass cube set atop a three-story granite base, and tells me that the bottom three stories used to be the Sofia City Library until some political wrangles during the chaotic nineties placed it in private hands.

We walk around the old Tsarist palace, which had once been the Ottoman administrative headquarters, then became a communist administrative center, and now houses two museums, where Shpatov points out a statue to the poet and communist organizer Nikola Vaptsarov, who attempted to organize a Bulgarian resistance against the Nazis. The Nazis tried him and shot him in 1942 without interference from the Tsar, and so during communist rule the government positioned his statue in such a way that the writer appears to be looking accusingly at the former palace.

After pointing out another dozen memorials and authors, Shpatov leads me to a swath of green lawn in the center of the city between the Neo-Renaissance Military Club and the gilded onion domes and gleaming eaves of the Russian Church. On this spot of parkland, Shpatov explains, there once stood a building that housed the most popular literary café of the 1930s. He shows me a satirical cartoon from a newspaper of the era; the artist has drawn caricatures of 107 of the city’s leading intellectuals, politicians, writers, and artists all gathered at their customary tables throughout the café. I feel his disappointment when he explains to me that, when the communist government commandeered control of intellectual and artistic circles, the café was shut down and fell into disrepair. In the 1970s a municipal government interested in extending the green spaces at the city center removed the structure, leaving a grassy square in its stead.

Thoroughly chilled in the January air, Shpatov leads us a couple blocks east to Krivoto, a restaurant popular with the students of Sofia University, which he’s immortalized in one of his short stories. He insists that it’s a Sofia tradition in winter to drink a Stolichno dark beer at one of the restaurant’s tables, so we sit and order a beer then a couple more while he tells me about his own writing.

Unlike the majority of writers I’ve interviewed, Shpatov makes no claims to being a literary protégé as a child. Instead, he remembers getting off to a bad start with his high school Bulgarian literature teacher— who ended up teaching him all four years—when he skipped her class to attend a football (futbol) game. Later, he claims he made a similar impression on his English teacher when that teacher asked him to create an anthology of poems for the class, and Shpatov crafted a collection of songs to be sung in Levski Stadium, where the professional football club plays. “I got the lowest grade for the course; which is to be expected,” he says.

Despite his descriptions of his own poor performance, he credits his English literature class, which was a mandatory part of his studies at the American College, with providing him a thought-provoking contrast to his Bulgarian literary studies. In the tenth grade he studied Hamlet in his English class and also in Bulgarian translation. In Bulgarian he was assigned to write an essay on the theme of madness in the play, while his English teacher’s assignment was more creative. The students were required to perform a scene. Some of his classmates rented costumes from the National Opera, but he and his friend chose an easier way out. “We did a puppet show, so we could read the text.” He laughs and mimics clumsily holding a script and reading while also manipulating a puppet.

Shpatov felt like the approach of his English teachers humanized the writers he studied while his Bulgarian teacher lionized them. “Which Geo Milev is more memorable,” he asks, “the guy with the scar or the guy with the hair?” He points out that the statue, which the city erected in the park named after the poet, features that elegant sweep of hair.

In the tenth or eleventh grade, Shpatov isn’t exactly sure which, he was assigned to write an essay in the style of Aleko Konstantinov, the naturalist who is one of Bulgaria’s most beloved writers, and he was surprised when his Bulgarian teacher awarded him a “6,” the equivalent of an “A” in the Bulgarian system. He sent the assignment to a satirical newspaper. His grandfather was a subscriber, so Shpatov hoped to surprise the old man. One of the editors liked the submission and asked the young writer to send some stories, so Shpatov quickly sent five. The editor chose one then helped him edit it down from twelve pages to two. “At the last moment though,” Sphatov says, “the chief editor stepped in and what got published was two paragraphs, 211 words, stripped from the initial 3,774.” He vowed that someday he would publish the story in full, and in fact a later version of the story appeared in his first collection, Footnotes, which was published in 2005, when he was twenty.

His approach to publication at the time was fairly typical of young writers in Bulgaria. Because the country’s population is only seven million, profits from the sales of story collections tend to be modest. As a result, publishing companies will only print and help distribute a new writer’s book if the writer pays for the costs of the printing. Shpatov approached a pastry shop owned by a relative who has an appreciation for the arts and asked him to sponsor the publication of the book. (Later, the shop owner handed out copies of the book to his customers.) But Shpatov knew he also needed an editor to help him hone the manuscript. He had a high school friend whose father was Deyan Enev, a well-known writer and editor, and he asked his friend if his father would consider editing his stories for him. The friend asked for a printout of the collection and told Shpatov he would wait for the opportune moment. A few weeks later, Shpatov’s friend told him he was in luck: “One day, my dad was on the toilet, and he says, ‘Give me something to read.’ So I handed him your stories.” Enev agreed to work with him.

Footnotes, published by Vesela Lyutzkanova Publishing House, won the award for “Best Fiction Debut” in the 34th Yuzhna Prolet National Literary Competition in 2006. Shpatov sold out his first printing of five hundred copies and printed another thousand, which also sold well. “I got the most money from that first book,” Shpatov laughs, “because it was all for me.” (Because he had paid the cost for the publication and carried the books around town to sell at various bookstores, he earned a higher percentage of the actual sales price than he would after he signed a formal contract with publishers in subsequent deals.)

Two year later, Shpatov had written enough new stories for a follow-up collection. He had maintained enough name recognition that he still drew invitations for interviews from newspapers and television talk shows, and after one TV interview with a successful Bulgarian publisher, the woman told him she wanted to publish his next collection. Shpatov’s second collection, Footnote Stories, was published by Janet 45, a press based in Plovdiv, in 2008.

The most distinctive quality of Shpatov’s stories is their setting in the capital city. After World War II, communist censors imposed socialist realist values on the country; fictions that centered the wisdom of the peasantry were favored over stories about urbanites. Throughout the history of the Soviet block, it was common for leaders to order intellectuals out of the cities and into the countryside where the peasants were encouraged to knock them down a peg by forcing them to adopt country mannerisms and values. Some of this anti-intellectualism continues today.

“All of our great short stories are about the village,” Shpatov says. He references Yordan Radichkov, another of the writers carved in stone beside the former palace. “Radichkov said his biggest regret was that he ‘got lured into Sofia.’”

It was Garth Greenwell who reassured Shpatov it was okay to write about the city. Greenwell was teaching English to high schoolers at the American College of Sofia, and Shpatov came to volunteer as a translator for foreign teachers on a parent-teacher conference night. The two started talking and eventually Greenwell gave Shpatov a copy of James Joyce’s Dubliners. “Here’s a story about the city,” Greenwell said. It confirmed Shpatov’s own ambitions to draft a book of tales from Sofia.

His next collection, #LiveFromSofia, was published in 2014. It was an immediate success, selling well and winning the Sofia prize for literature, earning him invitations to do readings in Plovdiv and Varna, and causing Sofia city officials to approach him about some sort of joint venture. The writer suggested turning the abandoned glass kiosk into a library and initiating a literary tour. The library doesn’t just loan books; it’s a center for collecting donations of old books from city residents which are in turn donated to rural libraries around the country. “Last year, we donated eight thousand books,” he says.

Shpatov had wanted the cover of #LiveFromSofia to look like a label from a beer bottle, a reference to one of its stories, “Beers by the National Theater,” and he thought he might be able to form a marketing partnership with the Stolichno beer company (whose product we are drinking) because Stolichno, translated, means “of the Capital.” Unfortunately, the company rejected his attempts to partner with them. Shpatov brushed off his disappointment and set about making his own promotion. He looked for beer bottles that were the appropriate size and shape to hold his book cover “label” and discovered that Stolichno Weiss bottles were the exact shape he needed. He bought five crates, 100 bottles in all, and sanded off the logo on the cap and steamed off the labels. The plan was to replace both the cap and the labels with copies of the mock beer label that appears on the cover of his collection and then hand out a beer with each of the first hundred books he sold at the annual Sofia Christmas Book Fair.

It was mind-numbing work, he tells me, so he enlisted a group of friends to help him. The waitress brings him his next beer, and he admires it. “In the process, we wound up drinking an entire crate,” he says, smiling, “so we only wound up with eighty beers.”

I nod. It seems about right to me. In Shpatov’s world, like all those writers from the 1930s he loves, there’s a blurry line between his friendships, his adventures, and his fictions. It’s not just the art of writing he loves, but also the community that embraces it and the history that links him to all those Bulgarian heroes whose names litter the map of his city and are etched into the bases of the statues that populate the parks of downtown Sofia.

Bulgaria is a country of seven million people located on the eastern edge of the European continent. It borders Turkey to the southeast, Greece to the south, the Black Sea to the east, and Romania to the north. Until 1989 it was a member of the Soviet communist bloc. The end of Soviet control led to a free-for-all for resources, the rise of mafias and oligarchs, and a full-scale economic collapse in 1997. The European Union accepted the country in 2007, and economic growth has been steady since then, but its income levels are still among the poorest in Europe.

The Bulgarian word for book is kneega. It’s a Slavic word that sounds closer to the Turkish word for book, kitap, to me. Certainly it’s quite different from the neighboring Albanian word libër, which comes from the Italian libro, derived from the Greek vivlio. The Ottoman Turks controlled Bulgaria for about five hundred years, until 1878, but the word probably predates this influence (and most likely joined the Slavic tongues during the Islamic incursions into the Caucasus Mountains that began in the 800s).

In the 19th century Bulgaria reemerged as a nation. With support from Russia, a country of fellow Orthodox Christian Slavs, the Bulgarians kicked out their Ottoman overlords and declared themselves a nation-state. If you tour Bulgaria, you can see the architectural remains of this transition. In the central city of Plovdiv, about 130 kilometers southeast of Sofia, on a defensible hill where the Romans left behind a temple and a theater, Christian merchants in the 19th century built richly decorated wood-framed homes, creating a neighborhood that was separate and distinct from the Ottoman mosques, hammams, bazaars, and public buildings located beside the river in the valley below. It was a time of prosperity for the rising middle class in Bulgaria and a literary awakening for poets and intellectuals who wrote epic poems about the revolutionaries who the Turks kept capturing and turning into martyrs.

But it wasn’t until the eve of independence that my favorite early Bulgarian writer began to tumble through the Balkan atmosphere. Aleko Konstantinov wrote his first stories in the 1890s. Aleko, as he’s referred to in Bulgaria, is the nation’s better-looking version of Mark Twain. He was a refreshing figure of liberal thought and common sense in his day, an advocate of hiking and the benefits of fitness, and a crusader against snake oil salesmen, montebanks, and hucksters, especially those of the political variety.

Aleko’s greatest character is named Bai Ganyo. (The word Bai is an honorific used for an older accomplished man, and probably comes from the Turkish Bey, which became the Arabic Beg. The title once referred to a tribal chief, but during Ottoman times slowly came to be used in the way that “Colonel” was used in the antebellum South, which is to say it was a pompous term used by a macho culture to distinguish wealthy men who claimed to possess important cultural insights but were typically rich bores.) Bai Ganyo is an indelible figure in Bulgarian culture and thought. The character is a satirical depiction of a nouveaux riche bully who dresses in traditional Bulgarian dress and is forever showing up at parties and cafes in Prague and other Eastern European capitals, where he acts boorishly and embarrasses the other Bulgarians in the vicinity. For Americans he is a thoroughly modern character: Picture yourself sitting at a corner café in Paris, one of those little overpriced coffee shops near Rue de Temple in the Marais, and imagine that a loud American wearing a MAGA hat takes the table beside your own and begins pontificating loudly about the inferior quality of French beer and the general rudeness of French citizens.

Ask any eighth grader in Bulgaria if they know Bai Ganyo, and they’ll nod enthusiastically. However, adult Bulgarians are hesitant when they hear a foreigner mention the character. Bai Ganyo represents every native impulse that liberal-minded Bulgarians despise in their uncles and cousins. Like references to your own Trump-supporting uncle, the situation is complicated. It’s okay for you to make fun of your uncle but not okay for others to chime in.

At the entrance to the strolling shopping street a few blocks from the National Theater where I met Shpatov, the city has erected a life-sized bronze of Aleko. The local tour guides don’t bother to include the statue in their circuit of the downtown, preferring the easier-to-explain statues of Imperial-era horseback tsars raising swords and the statues of communist-era workers raising rifles in triumph. Aleko’s writings advocate something more complicated than nationalist or socialist sentiments, something at once more profound and more ambitious. His writings satirized populist, self-serving, and simpleminded politicians. He was a Romantic from a middle-class family who ridiculed the corruption of more pragmatic and powerful men and, as a result, was assassinated before he was thirty-five years old. Bulgarians revere him as a sort of private national symbol, one that they know intimately but who they’re cautious about sharing with outsiders.

The Child Star

Ludmila Filipova is waiting for me behind the floor-to-ceiling windows at a table in the back of the Esterhasi Bar, just down from Eagle’s Bridge, a quarter mile east from the National Theater. The waiters know her. When I ask for her, they whisk me past an assembling party in the front of the restaurant, past the glass wall that partitions the quiet back room, to the small round table where she is seated. She stands to greet me. The author of twelve novels, Filipova has pale eyes and blonde hair and is wearing a black dress patterned with white dots and red poppies. I’ve seen Filipova’s books in translation at several of the bookstores in town, so it comes as a surprise when she tells me, in so many words, that before she became a writer, she was the last socialist princess of Bulgaria.

Novelist Ludmila Filipova, author of twelve books, including the best-seller The Parchment Maze (2013), translated by Angela Rodel and David Mossop, at Esterhasi Bar in Sofia.

Filipova has a risotto coming, and I order a white wine to match the glass that is sitting before her on the table, then take out my reporter’s notebook, click my ballpoint, and start to ask a question. Filipova smiles confidently then begins to speak before I can get any words out. There is no need for questions. I write steadily for the next ninety minutes. Her story is unlike that of any writer I have ever met, which is extraordinary because across the many countries where I have sat in bars and cafes and interviewed poets and authors, certain patterns have emerged. She fits none of them.

Filipova’s grandfather was Grisha Filipov, a Russian-speaking Bulgarian who fought against the fascist in World War II, was arrested by them during the war, then released when the Soviets arrived. He was raised in the Ukraine, came to Bulgaria when he was nineteen, and eventually rose to become a member of the Bulgarian Politburo, the clique of communist leaders who ruled the country from the end of World War II until 1989. From 1981 to 1986 he was the leader of the National Assembly and widely acknowledged as the right-hand man of Todor Zhivkov, the General Secretary of the Bulgarian Communist Party from 1954 and the face of Big Brother in Bulgaria during communist times. Zhivkov was famous as the longest serving dictator in the Eastern Bloc, and Filipova’s grandfather was his chief lieutenant. For generations, her grandfather was one of the most feared men in Bulgaria or one of the most respected, depending on one’s perspective.

Filipova shows me a photo on her phone. It was taken on a national day of celebration in 1981, and in it she is four years old, standing behind the communist leaders atop the tomb of Georgi Dimitrov, the embalmed first dictator of communist Bulgaria, while cadres of workers march by on the avenue below. The tomb has since been destroyed. It used to sit in the park where I met Shpatov. In the winter there is a Christmas market adjacent to where it once stood. Sometimes a Christmas tree is erected on the pavement—all that remains of the former temple to communism.

Filipova loved her grandfather. From her perspective, he was the economic genius who spotted the failings of socialism and began to permit some free market reforms a decade before Mikhaïl Gorbachev opened the doors to Russian Glasnost.

“I was age thirteen or fourteen at the time of the revolution,” Filipova says, describing the end of communist rule in Bulgaria. “Imagine a kind of princess, going to palaces and resorts; my godmother was the daughter of the socialist leader.”

Filipova was also a child actor. With her blonde hair and blue eyes, she was selected to play Bulgarian girls in some of Bulgaria’s most famous films from the communist era, including a small part in the popular children’s movie Dog in a Drawer.

Then 1989 arrived and the communists fell. One day, her mother woke her up and told her that she wouldn’t be going to school today; her grandfather had been removed from power. Overnight, like Disney’s Russian tsarina Anastasia, her privilege fell away. She became an object of ridicule, she says; her teachers laughed at her. In the streets, people recognized her and jeered. She remembers their calls, “Oh, your grandfather is in prison. Ha, ha, ha!” She was thirteen.

At fourteen she got a job in a café serving sandwiches and coffee, and she worked hard in school. Her mother pressured her to be practical, and she eventually earned a degree in economics. During the nineties she worked for one of Bulgaria’s new oligarchs. She says she used the experience to gather information for future books; she wanted to tell the story of Bulgaria’s changing society and economy from her own perspective. By 2005 she had a partial draft written. Her grandfather had died of cancer in 1994 then her father had passed away, and now her mother was ill and in the hospital. “After ’89, the new heroes of Bulgaria needed enemies,” she says. “They picked the top three families of the socialist times, and they tried to say that they are responsible for all the bad things that happened to Bulgaria.”

Her grandfather had been jailed; her parents both lost their jobs. She watched her father hock the family’s possessions to put food on the table. They lost everything. “My parents and relatives died from the stress,” she says.

She showed her developing novel to her mother in the hospital. Her mother had never been supportive of her impulses to paint or write when she was younger, but she liked what she saw in the early drafts, and she urged her to keep working on it. Filipova’s first book fictionalizes the Bulgarian transition from communism to free market capitalism and then the nineties free-for-all. It includes insights she received from her grandfather. “I started writing with no desire to be a writer,” she says. “I simply wanted to give information.”

In Bulgaria a book that sells three thousand copies is considered a success. Filipova says that her first book, Anatomy of Illusion, sold ten thousand copies in one month and has sold as many as seventy thousand copies to date. “I started with Ciela [Publishing],” she says. “I was one of their best, best writers, but didn’t approve of their professional attitude.” Unhappy with the support she received for the books she wrote after Anatomy of Illusion, she switched publishers, then switched again, eventually landing with Enthusiast Publishing. Ciela still plays a role in the distribution of her novels, but she says that Enthusiast lives up to their name by “always trying to invent and develop new ideas for making bridges between writers and readers.” She says she likes that they are willing to communicate and work with writers “seven days per week.” Indeed, Filipova’s research trips frequently take her out of the country. She was in Brazil just before our meeting, and when I try to contact her for a few follow-up questions, it takes several days before I hear from her. When I do, she explains that she was “on a Turkish mountain researching a topic without a phone connection.” It’s easy to see why she is eager to work with editors willing to take her calls on the weekends.

Filipova has published eleven novels since the release of her debut, and seven of them have gone on to become best-sellers. She enjoys researching then dramatizing criminal conspiracies, social and political issues, or regional theories about history. To some extent, she has carved out a role for herself as the Dan Brown of Bulgaria; she identifies attractive conspiracy theories and fictionalizes them. “Even now, I’m not calling myself a writer,” she says. “I’m calling myself a ‘distributor of knowledge.’” Filipova enjoys switching genres with each new book, from historical to documentary to mystical. While working on a book she tries to avoid similar books or even television shows in a similar genre, and she dives into research in dramatic fashion. For a book about Antarctica, for instance, she traveled to Antarctica on three different expeditions. Before publishing her last two books, the science fiction novels The Reason and The Contact, she earned a masters degree in astronomy from Sofia University.

She confesses to being a highly structured writer: She maps out her plots, creates her characters, and adds them to her outlines—sure of her endings long before she nears the completion of her first drafts. “Some writers, they say they prefer not to know the ending,” she says. “It’s considered very creative and very high level; but it’s very important to know the end because it’s very efficient. Organization is very important if you want to make a good story.”

Filipova says that she has faced criticism from the established literary circles in Sofia which, she says, prefer to see novel writing as an art that refuses to make concessions to popular tastes. When she began writing, Bulgarian literary circles were dominated by “a lot of selfishness and ego” that looked down their noses at popular fictions, she says. “Before me, they all try to become these god writers. They wrote things that were not very understandable, that were very complicated and that were without story.”

Early on she felt pressure to change. “After my first book, they said it was successful ‘because she’s blonde.’ After my second, ‘it’s because she’s blonde.’” But Filipova followed her own path, and now she sees many more Bulgarian writers creating and publishing popular fiction in different genres.

Nowadays, Filipova says that she is content with her research and her work. Bulgaria continues to be beset by political and economic problems (tensions that have been exacerbated by the global pandemic) but Filipova remains optimistic and supportive of the current government. “Bulgarians are very negative,” she says, as she takes a last bite of her salad. “They like to complain, but I’m a very positive person.”

The fall of communism in Bulgaria in 1989 led to a period of economic and societal chaos. As a result of the dissolution of the interdependent communist block system, in the 1990s the standard of living fell in Bulgaria by an estimated 40 percent. In 1997, after a series of wild fluctuations, inflation peaked at 311 percent and the currency collapsed. A newly elected government stepped in and, with help from the International Monetary Fund, started to put the economy on firmer ground, but not before an estimated one million Bulgarians left the country looking for work and better prospects. Nearly half a million headed for Turkey while another three hundred thousand emigrated to the United States.

Since the country’s acceptance into the European Union in 2007, these numbers have stabilized, but it has become a common part of the Bulgarian experience to know somebody—a brother, a sister, a cousin, a friend—who has spent time working in the United States.

Bulgarian fiction and film reflect this. For example, the recent Bulgarian film, 18% Gray, which appeared in Bulgarian theaters on January 24, 2020, is about a Bulgarian immigrant’s vehicular odyssey across the United States. Like many thoughtful films in Bulgaria, the movie started out as a novel, this one by Zachary Karabashliev.

The Buglarian Kerouac

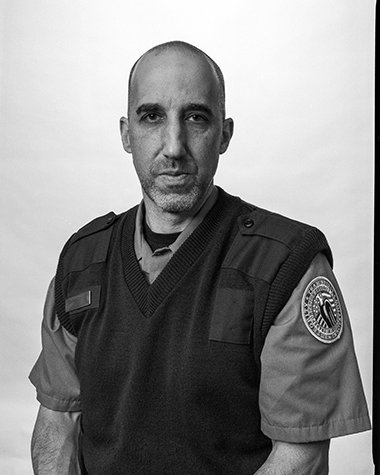

Zachary Karabashliev meets me on Vitosha Boulevard, the pedestrian thoroughfare for shopping, strolling, and people watching that is fronted by the bronze statue of Aleko. It is just after twilight in November, and the bricks of the boulevard gleam with the reflected glare of the streetlights and the cafes. Karabashliev is in his early fifties, fit and youthful. He has a shock of gray hair, a long nose, and a pugnacious chin. He is dressed in a dark vest, white button-down with the collar undone, and a loosened striped tie. He has just completed a full day on the job. As both a famous novelist and the editor in chief of the country’s largest publisher, Karabashliev probably knows more about Bulgaria’s literary life than anybody else in the country.

We leave the avenue and walk in the direction of his apartment, stopping a couple blocks away at an out-of-date bar he says he’s not sure he’s ever entered. Inside we find leather stools and orange velour textures. We take a small table in the back room where it is quieter, order a pair of Irish whiskeys, and begin our conversation.

The former headquarters of the Bulgarian Communist Party in downtown Sofia (left); novelist, playwright, and screenwriter Zachary Karabashliev, who is also editor in chief of Ciela Publishing, at Orisha Bar & Dinner in Sofia.

His company, Ciela Publishing, founded by a pair of lawyers twenty-six years ago, was originally focused on disseminating legal texts. In its first decade the house added fiction, nonfiction, and young adult titles, and it continues to grow. The company employs six full-time editors and last year published close to two hundred books, Karabashliev tells me. Half are original Bulgarian titles; the other half are books in translation.

Karabashliev’s fame as a writer has followed a similar rising curve. He says he always wanted to write, but his environment in the Black Sea city of Varna, where he was born and raised, was not conducive to such a dream. “As a kid, I never saw a real writer,” he says. “I thought all the writers were dead or lived someplace else.” From age 18 to 20, during a time when Bulgaria was still socialist, Karabashliev was required to serve in the Bulgarian military, and afterward, when he was in college, there was more emphasis on criticism than creative writing. “Roland Barthes, Julia Kristeva, I was very influenced by Structuralism,” he says. “Deconstruction was big.”

In 1993, he entered a short story in a national student literary contest and won an award equivalent to a month’s salary. He remembers the date, May 18, because the next day his daughter was born. He continued to write and work in Bulgaria, but the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the fall of the communist authorities had created a political and then an economic crisis.

“When we emigrated there was only one bookstore open in Varna,” he says. “I wanted to be a writer so bad. I was writing short stories [that were] published in newspapers, but the idea of being a writer was absurdly unthinkable at the time.”

In 1997 the economy completely collapsed, and Karabashliev and his wife searched for other options. “It makes me angry to remember,” he says. “You have no idea how fucked up this place was. In 1997, the monthly salary for teachers was ten American dollars.”

So he moved to the United States, settling for two years in Columbus, Ohio, where he worked the night shift for Anheuser Busch and studied English with other refugees during the day. “I took French in high school, and I knew about three words of French,” he says. “I only knew English through the lyrics of songs—Iron Maiden, Metallica, Pink Floyd—so you can imagine the vastness of my vocabulary when I arrived. It was pathetic.”

After two years in Ohio, Karabashliev relocated to San Diego to work and raise his daughter while also continuing to write plays, screenplays, short stories, and novels. He tried writing in English, which he now speaks fluently with an American accent, with little success. His breakthrough occurred in 2008 when he sent his manuscript of a finished Bulgarian novel, 18% Gray, home for a read by one of his former professors in Varna. The professor shared it with a friend at Ciela; they liked it and agreed to publish it.

He credits the move to the United States with changing his life and also changing the way he thought about language. “Because I didn’t understand English at all,” he says, “for the first time in my life, it was necessary for me to think before I spoke, and it changed something in my perspective.” His circumstances were also different. He’d left his friends behind in Bulgaria. “There’s something about writing in the U.S., it made my job slightly easier. I could be more lonely over there. Socially, I was not as engaged as I am now.”

After Ciela agreed to publish his novel, the move from acceptance to final printing was quick. The speed with which a book can move from manuscript to distributed novel is one of the things he enjoys about the Bulgarian marketplace. “I have no idea why it takes so long in the U.S.,” he says. “I always thought that it seemed very weird.” Before the year was out, his book was on the shelves in Bulgaria, and Karabashliev flew home to promote it.

Things had improved in his home country since he had left eleven years earlier. Now bookstores and bright cafes dotted the streets of Sofia. Salaries were rising; even the teachers were doing better. (In recent years, the public school teachers of Bulgaria have been given at least two highly publicized raises.) And Sofia has always been a gorgeous place. In addition to the National Theater, there’s a jewel-box opera house, cathedrals, Roman ruins, a historic mosque, a historic Jewish temple and a giant Communist-era auditorium. Plus the Bulgarian capital city hosts film festivals and international sports contests, and there’s a blossoming café culture.

On top of all that, the early reviews of Karabashliev’s book were very strong. “I will never forget the first article that came out,” he says. He was interviewed by a reporter from a prominent newspaper who hadn’t read his novel. “She asked me what it was about.”

“It’s a road trip. It’s about lust and love and—”

“Oh, is it like Kerouac?”

“No—”

“‘I love Kerouac. I love Kerouac,’ she said.”

Karabashliev laughs. “As a student I loved Kerouac too, but… the next day, the newspaper comes out with an article with the headline, ‘The Bulgarian Kerouac!’”

The article helped his sales, and he went back and reread Kerouac. “I didn’t care for it,” he says.

He flew back to the United States and resumed his life there, this time in San Diego, where he worked as a part-time professional photographer—taking portraits and photographing weddings—and tending bar at a Sheraton. In Bulgaria, meanwhile, he was a best-selling novelist with a burgeoning reputation and multiple opportunities. So, in 2014 he accepted the job running Ciela and moved back to Bulgaria, taking up residence in a top-floor flat in the heart of the city.

In the years since, he has become one of Bulgaria’s most prominent artists. The day after our meeting, about a month before the arrival of COVID-19, I go to a theater to watch the film Jojo Rabbit, and when the lights lower, the trailer for the film version of Karabashliev’s novel fills the screen.

I ask him about the economics of publishing in Bulgaria. “In Bulgaria, when you publish a book, you get a small advance, or even, you don’t,” he says, “but you get a royalty statement every three months. And that’s super solid. Whatever you sell, it’s yours.”

The industry of publishing is greatly affected by the size of its language base. The number of potential readers a language contains determines not only how many publishing companies exist but also how many writers can survive solely on the profits of their artistic output. In some countries, there are simply not enough readers to enable any full-time writers to survive. I ask Karabashliev if there are enough Bulgarian readers for his publishing house to offer writers contracts that are large enough to live on.

“The easiest way to explain it is to compare the Bulgarian to the U.S. market,” he says. There are between seven and eight million Bulgarian speakers in the world, he says, whereas there are about three-hundred million people who speak English in the United States. Bulgaria is about fifty times smaller, say forty to be on the safe side,” he explains. “The logic would be this: If a novel in the U.S. sells 10,000 copies, that equals 250 copies in Bulgaria. But if a book in Bulgaria sells 10,000 copies that is equal to 400,000 copies in the U.S.” He drains his whiskey. “That would eventually make me a millionaire.” He smiles. “I just want to clarify the restrictions I work under. Sometimes it’s so discouraging.”

18% Gray has sold about 70,000 copies over the course of the eleven years it has been in print, Karabashliev says. He’s no millionaire, but he appears happy with his position: He is the managing editor of Ciela, the movie version of his successful novel is about to be released, he’s recently remarried to a political scientist, and he has a three-year-old daughter waiting for him at home.

He tells me that his earlier marriage ended in divorce while he was in the United States, and the memory causes him to reflect on his peripatetic life and the costs associated with pulling up stakes and moving from one continent to the next. He recalls listening to Ha Jin, the Boston University professor and writer who emigrated to the United States from China following the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, speaking about the subject on NPR or a podcast. Karabashliev remembers him saying, “‘I know it would have been better to have been stuck in China and be a Chinese writer, but I chose to be something else.” After he returned to Bulgaria, Karabashliev met Mo Yan, the Chinese Nobel Laureate in literature, and realized that here was the example that Ha Jin was referring to, the man who stayed home, who wrote in Chinese, who wrote stories about his home village. Karabashliev turns the idea over as we speak. “Can you not be both?” he asks. He glances at me. “To this day, I have no answers.”

He thinks back to his early arrival in the United States. “I remember when I first landed in Newark, New Jersey. The first breath I took, there was openness in the air. I can’t express this. We stepped in a Burger King, and I remember the air. I was like, ‘Shit…the openness.’ I’ve never dreamed of being an immigrant in Europe. In the U.S., I never was considered an immigrant, never for a moment.”

But his circumstances changed after 18% Gray won the Bulgarian National Book Award. At some point he had more opportunities for work in Sofia than he did in San Diego, and he confesses that he could not imagine himself being buried in the United States, or any place other than Bulgaria.

He talks about his work as an editor, the magic of picking up a submission by an unpublished writer and being drawn into the narrative. “You cannot engineer it,” he says. “You cannot produce it.” He’s often been tempted, he admits, to apply a heavy hand to works that seem like they would benefit from the imposition of his tastes, but he’s made a firm decision to avoid heavily editing his writers’ works, and he’s stuck with it.

He says he is proud of a recent decision to print a thousand-page book about the Bulgarian concentration camp in the town of Belene that was infamous during communist times. “The decision there was not to create a commercial success,” he says, “but just to publish it.” He insists on paying for our whiskeys, and we move toward the street. His wife and daughter are waiting. “The funny thing is, [the book] became a commercial success anyway.” He hasn’t eaten yet, and he stretches out his hand to say farewell. Then the Bulgarian Kerouac goes home to make homemade pizza with his family.

Bulgaria’s involvement in World War II, like everything else about the country, is unique. Forced into a reluctant alliance with Nazi Germany despite the country’s warm historic relations with Russia, the Bulgarian Tsar, Boris III, sent Bulgarian troops to the front lines, but he refused to allow the Nazis to round up or harm Bulgaria’s Jewish citizens. Before the war’s end, Boris was dead from Nazi poisoning and had been succeeded by his six-year-old son, Simeon II. The young tsar was quickly sent into exile when the Soviets invaded.

From the end of the Second World War until 1989, the Bulgarian Communist Party controlled the political, economic, intellectual, and artistic life of Bulgaria, and the communists left more than just a few statues of flower girls behind. The communists certainly encouraged the worship of all those left-leaning writers whose names are still scattered across the map of the city, attached to streets, neighborhoods, subway stops, buildings, theaters, and schools.

Among the many successful living writers from communist times, a few have been able to adapt and to continue to write and publish, and also to find work as editors of magazines and as writing instructors in the democratic and capitalist system.

The Master

I wait for Vladimir Zarev on a Sunday in front of the National Theater, the same spot where I met the younger Shpatov. Born in 1947, the son of a literature professor, Zarev was famous during communist times and continues to be successful today. He studied Bulgarian philology at Sofia University and published his first book of poems, Riot of Emotions, in 1972. In the years since, he’s published ten novels, multiple volumes of short stories, and two nonfiction books, many of which have been translated into German, Turkish, and other languages.

Zarev has informed me by text message that his daughter will translate for us, and she arrives before the writer. She tells me she is a headhunter for business professionals as she leads me around the corner to Momento, a modern café filled with Pottery Barn–style furnishings. Her 72-year-old father soon joins us at a wooden table.

The St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral (left); novelist Vladimir Zarev, who is also editor of the literary magazine Savremennik, or Contemporary, at Cafe Memento in Sofia.

Zarev is bald on top with a round face and a white beard. He wears glasses and occasionally touches his chin in a gesture that seems thoughtful and slightly reticent. I ask him when he first thought of himself as a writer, and he says when he was three years old…then he waits a beat, and his daughter translates that he was only joking.

He describes growing up in a house where his parents kept a “huge library” that intimidated him. It had a cold and Gothic feel, he says, and he avoided it until he was in the sixth grade, when all that changed. Before long he was skipping school to read books. By the eighth grade, he had fallen in love with Dostoyevsky and was writing his first poems. Eventually he went to university and studied the history, structure, and development of languages then joined the military and wrote his first book.

It’s hard to get him to talk about the details of those days. He would rather speak philosophically about how as a writer he resisted the strictures of his era, about how the act of writing under the communists was an act of resistance. “We craved freedom,” he says, “because freedom is a form of difference. The more different a person is, the more free he is. We were forbidden to be different.” It is one of the reasons he started writing—to be free. He says that the writers of the era tried to master the language, constantly working to say things that could be understood to mean two things. It’s how they avoided censorship.

I ask him if he was explicitly told what to write, and he says that nobody told him what to write; instead, there were people who carefully read anything he wrote and occasionally rejected them. For example, Exodus, the second book of his historical trilogy—after Genesis and before The Choice—originally contained a character who was a writer and was sent to a gulag. The censor, after reading Zarev’s submitted draft, informed him that his book wouldn’t be released with this character in it. Zarev removed the character.

Despite such pressure, the writer successfully published four acclaimed novels during communist times, and he was appointed editor of the country’s most prestigious literary magazine, Savremennik, or Contemporary. After the change-over to democracy and capitalism, he spearheaded efforts to preserve the magazine, and he still edits it today.

I describe the literary café from the thirties that Shpatov told me about during our literary tour then ask Zarev if places like that existed for writers during the 1970s. “Back then there was a very strong union of writers,” he says. He describes a large building where the publishing houses and magazines had headquarters. On the first floor there was a cafeteria and a restaurant. It was a club, of sorts, that was only for writers. “If you were a regular person you couldn’t go.”

During these times, the political party only favored writers who supported the party’s agendas. He was a member of the writers union, although there were some great writers who were never permitted to become members, he says. There were two ways to be admitted: Either you were voted in by the party or you were accepted after popular acclaim. The party writers received all the awards and earned all the benefits. The quality of the text wasn’t that important, even though there were some great writers back then, he says. The best ones tended to write historical novels because they were not forbidden, and they tried to masquerade alternative messages in their works. “The writers were taken very good care of by the political party,” he says. For example, there were large vacation homes by the sea that were available to them.

“Books back then were a huge matter,” he says. There was only one television channel, and it was a time before the internet or handheld devices. The only movies you could watch were made by the Soviet Union, and people weren’t interested in watching those. “But this wasn’t the real reason books were important,” he says. “If you read a good book, you might consider yourself a rebel; it was a form of social unity; a good book or a good movie was difficult to find; searching for them was a subconscious way to rebel against society’s rules.”

Now that democracy is here, Zarev says, he regrets that the importance of books has faded and they don’t seem to unite the people as much. Artists can say what they want, and as a result, art has lost a little of its glitter, he says.

Yet he still writes. “It’s a beautiful thing to write. When I write, it feels like somebody is dictating to me from someplace up above; it gives meaning to my life; it’s a form of separating the author from death.”

Zarev is pleased that his books continue to be translated into German and other languages, pleased at the attention they’ve garnered from the German critics and press, and he also continues to teach. For the last decade he has taught creative writing workshops, typically with twenty students, organized by the National Palace of Culture. He says he tries to persuade his students that writing is an art form that cannot be taught, that there are only two ways to learn to write well, and those are: to learn by doing—to learn from your mistakes, slowly and painfully—and also to learn from the greatest writers in the world by reading them.

When he was in university as a young man, Zarev craved the opportunity to learn from great writers. It wasn’t until the late seventies that Americans were permitted to be translated into Bulgarian but then he immediately fell in love with Hemingway and Salinger—Faulkner most of all. He learned psychology from Dostoyevsky, he says, and Faulkner taught him how to create atmosphere.

Zarev constructs his books thematically, he says, and he has repeatedly explored two major themes in his work: The first is the problem of power, the way it can be manipulated, the way it corrupts, the way the powerful change the notion of power itself. “Beauty is power, money is power, art is power; every writer is a charming enslaver,” he says. And the second is the fear of death, the way that fear encourages creativity.

“Have you ever thought about why God kicks Adam and Eve out of heaven?” Zarev asks. “There’s honey and butter in heaven; there are no animals in heaven; no enemies; it’s warm and cozy. There is nothing left for Adam and Eve to do; it’s making them lazy, and they start to lose their minds.”

From Zarev’s perspective, God sends the serpent on purpose, so he can kick Adam and Eve out of the Garden, and they can start to use their imaginations to survive. “When they become mortal, they have to come up with fire, with animal skins so they don’t freeze, with different weapons, with electricity, energy.”

For Zarev, there is a small socialist message in death, although he doesn’t describe it that way; what he says is, “Death is the only way that all of us can be equal. The ill die, but also the healthy; the poor and the rich; ugly and pretty; it’s the only form of equity that we’ve been given.”

I ask him about the work of young Bulgarian writers, and he says he’s pleased that people can write what they want to write. He notes that the influence of other European writers on Bulgarian authors is more evident today, and he believes that literature has been undergoing a Renaissance in Bulgaria in recent years. Like the younger writers I interviewed before him, he is optimistic and upbeat when speaking about the future of writing in his country. I ask him about his father, the college professor with the large library. Would he be happy with the state of the country today?

Zarev smiles and nods, “Da,” he says. He thinks his father would be happy with the changes.

It is nearly six months later as I walk back through City Garden, the park in front of the National Theater. Like most of the city’s public spaces during the pandemic, the theater closed for the spring, offered some outdoor shows during the summer and now has begun to perform before reduced audiences. Bulgarians have been lucky. Their government acted with foresight in the early stages of the pandemic, quickly closing schools and restricting international travel. The country’s small population and relatively low density has helped them to avoid a large infection rate. It is October, and the country of seven million has experienced fewer than a thousand deaths. Over at Ciela Publishing, Zachary Karabashliev tells me that in the springtime when the government closed the malls and the bookstores, he was worried that the company would have to begin to lay people off, but instead, Ciela launched a series of online promotions and marketing schemes that permitted them to maintain their work force.

In a country this old, it’s easy to view the pandemic as just one more placeholder in a timeline that stretches back beyond the Greeks and the Thracians to a 7,000 year-old necropolis in Varna containing treasures from an otherwise lost civilization, and to Neolithic cave art near the village of Rabisha that is older still.

I glance at the artifacts from Bulgaria’s more recent history that are visible from the steps of the theater. There is the stone that marks the spot where Aleko Konstantinov began his hiking club in 1895, and off to the east, rising above the theater, is Mount Vitosha that his club climbed later that day. There is the palace and the balcony where the tsar addressed jubilant crowds when the Ottomans were kicked out. It is the same balcony where the communist dictator, Georgi Dimitrov, addressed happy crowds when the tsar was kicked out. There’s the swath of pavement where Georgi Dimitrov’s marble mausoleum once stood, where Lyudmila Filipova once watched a parade as a child. There is the old library under the new hotel. There is the empty space where the literary café stood, and there is the repurposed glass cylinder where Alexander Shpatov’s library and info kiosk remain.

I glance up at the marble statues arranged on the pediment of the National Theater above me and notice for the first time that somebody has sarcastically gilded the willy of the littlest cherub hovering with some garlands in his hand beside the central figure of Apollo. It makes me laugh, and it seems a nice place to end this literary tour. The visual joke adds a humorous note to the classical themes that Vladimir Zarev spoke about. It also is a welcome reminder that the enthusiasm of youth can reshape our collective histories and help us to look forward to the possibilities of things yet to come. I walk to the glass walled library and put my mask on, making sure it covers my nose and mouth, before reaching for the handle and opening the door.

Stephen Morison Jr. is an American writer living in Bulgaria, where he is the dean of students at the American College of Sofia. His writings have appeared in the Sigh Press, Hippocampus Magazine, Antigonish Review, South Carolina Review, and other magazines. He is a contributing editor of Poets & Writers Magazine. His recollections of his meetings with Paul Bowles in Tangier, titled Talking With Paul, was published by Khbar Bladna in Tangier in June.