Writing can help us process trauma — whatever that means for you — as well as help others through our words. In this episode, David Chrisinger explains why stories can save us.

In the intro, thoughts on print distribution [Jane Friedman]; Hachette’s acquisition of Workman and why backlist is key [The New Publishing Standard]; Your Author Business Plan; The Magic Bakery.

Today’s show is sponsored by ProWritingAid, writing and editing software that goes way beyond just grammar and typo checking. With its detailed reports on how to improve your writing and integration with Scrivener, ProWritingAid will help you improve your book before you send it to an editor, agent or publisher. Check it out for free or get 25% off the premium edition at www.ProWritingAid.com/joanna.

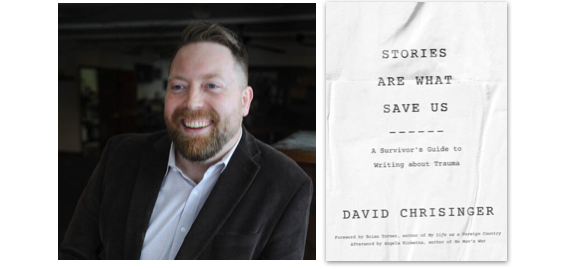

David Chrisinger is an award-winning nonfiction author and teaches writing at the University of Chicago. His latest book is Stories Are What Save Us: A Survivor’s Guide to Writing About Trauma.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- What is trauma and how is it different for different people?

- How to write about trauma without suffering further

- Is it possible to write a factual memoir?

- Tips for creating space between you and the ‘character’ you are writing about

- How do we deal with people who might be hurt by what we write?

You can find David Chrisinger at DavidChrisinger.com and on Twitter @StrongerAtBP

Transcript of interview with David Chrisinger

Joanna: David Chrisinger is an award-winning nonfiction author and teaches writing at the University of Chicago. His latest book is Stories Are What Save Us: A Survivor’s Guide to Writing About Trauma. Welcome, David.

David: Thank you so much for having me.

Joanna: It’s great to have you on the show.

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing.

David: I sometimes joke that I’m about a million miles from where I thought I was going to be when I started college because I went to college initially to be either a wildlife or a forest manager. And I even got certified to fight wildlife and forest fires.

For whatever reason, I realized halfway through that, it was more of an interest or a hobby, it wasn’t really a passion. And there were so many students that I was in classes with who I knew I was going to have to compete someday for a job and they were going to win. And so, I tried to think of, well, what do I think I can be the best at? What can I put everything into?

I settled on art and history. So, I did 3D art and focused on modern American and European history, and wrote lots of papers, obviously, in college. And it was my sophomore year that I took a historical methods course, actually doing historical research. And that’s where I think I really caught the writing bug.

I started to see history as this story that people told that was based on evidence, and interviews, and dozens of other kinds of records. And it was a way of people making sense of something. And there was just something about that, that really connected with me. And so I decided I wanted to be a history professor.

I graduated from college as the great recession was starting. And it turned out to be a pretty bad year to apply to graduate programs. I got in to the University of Chicago. I did my Master’s degree and then had a heart-to-heart with an advisor who said I think the academic job market’s not coming back and you should really think of doing something else.

I had no plan B. But he suggested I start looking for jobs in the federal government, maybe in public policy. A lot of social science folks end up in that sort of route.

And that’s what landed me at the U.S. Government Accountability Office, which is basically the research department, the evaluation department for Congress, and wrote a lot of reports and testimonies and had to really learn how to connect with an audience, with a reader that doesn’t have the same expertise or the same experience that the researchers have.

And I started doing my own writing. It’s been a very serendipitous journey to writing, and not something I intended to do from an early age.

Joanna: I think that’s fascinating. And it’s interesting because you mentioned history as a story. And I guess that’s also what we’re talking about in terms of what survivor means, and what trauma means, and what our writing is because when we write our writing’s only ever from one perspective, but as you say, we are connecting with an audience. I can see how your various interests have come together, which is fascinating.

Let’s get into the topic of the book because I think the word trauma, particularly at this time in history, is quite a difficult word. When people say trauma, it has very, very heavy connotations, maybe a very bad injury or experience of war.

What is trauma? How can the experience of what is traumatic differ between people, especially in these times?

David: It was 2017 I think the dictionary.com labeled trauma as the word of the year. That was something at least in the United States that was starting to get a lot more attention.

When I set out to write this book, it was one of those things where the timing lined up in a really odd way. And trust me, I would not have wished for a pandemic to try to help with book sales here, but I think the idea that we’ve all experienced something that is on that scale of trauma.

Now, there are things that are undeniably, clinically, by definition, traumatic. Like you mentioned, combat, people who survive sexual assaults, natural disasters, these situations where your life is really at risk.

And then on the other side of that scale, there are experiences where, let’s say, I behaved in a way that I’m not proud of or something outside of my control happened to me that changed the course of my life or helped me to see the world in a different way, not everyone’s going to call that trauma.

So I try to be pretty clear in the beginning of the book, that it’s not really my job as a teacher and it’s not really a reader’s job to say, ‘Oh, that wasn’t traumatic. Or, that doesn’t matter because it’s not as bad as this other thing.’

There’s this really famous quote from Viktor Frankl, who is a Holocaust survivor and a psychotherapist, and he said, ‘Trauma behaves much like a gas.’ So if you were to pump gas into a box, it doesn’t matter how big that box is, the gas is going to expand to fill the space. That’s what trauma does, too.

If it’s something that’s knocked you off the course of your life or something that makes you feel less whole than you used to feel, then to me, that’s the sign that there’s a story there.

There’s a story that when you’re ready to tell it, other people are going to want to hear.

Joanna: I think this is so important. And I was reading your book, and I felt this several times during the pandemic. it’s like, “I’m having a really difficult time right now but my life is very good compared to other people. So I feel guilty about labeling this in any way bad for me.”

And I say that because I feel like a lot of writers have the same experience or a lot of people have the same experience, which is, “oh, what’s happened to me isn’t as bad as what’s happened to X other person.” And even different people who go through a similar experience, someone might come out of that traumatized and another person can just write it off as not a big deal.

Personal perspective is so key, isn’t it, in terms of both your experience and also the reader’s experience?

David: That’s exactly right. And I would add to that when we set out or when I set out to write a story, that there’s going to be some kind of, let’s just call it trauma, whether it’s what other people would agree is trauma or not, beside the point, if I want to write about that. Obviously, that thing that happened or that experience that I had is going to be central to the story but it’s not the whole story.

And part of what I think makes personal essay writing and memoir so exciting to write and also so exciting to read is you can imagine yourself in the author’s position. How would I react to that? If that happened to me or what step would I take if I had survived that?

It’s almost like a computer simulation as you’re reading it. When I read a memoir, I’m not there to be voyeuristic of someone’s trauma. And in fact, that sometimes makes me feel quite uncomfortable as a reader if I’m starting to feel voyeuristic.

What I’m looking for in those stories is, okay, how did this person change? How did they react to this situation? What did they learn? How are they different?

That’s really where some of the ideas from this book came from, or, what were the kind of stories that resonated with me. And lots of times it was that there was a point to them. There was a reason why the person was sharing that story more than to say, ‘Here’s what happened,’ which lots of times, that’s a very appropriate thing to do, especially when you are documenting real traumatic events.

It’s incredibly important to say, here’s what happened. But when we’re talking about these kind of personal essays, memoirs, I think the thing that keeps the reader engaged is what did you learn from that?

Joanna: From the perspective of the person writing, so forget about publication and readers, we can talk about them in a minute but in terms of just writing:

Why is writing about trauma a helpful thing and how can we write about these dark and difficult times without going through more suffering or even drowning in these memories?

David: One of the most prolific researchers and writers, let’s call them, about this topic, has this rule that he calls the freakout rule, which is anytime that you want to express yourself in writing, if you start to feel that panic or that wave of depression, that freakout, that’s a signal from your body that you’re just probably not ready to do that kind of writing. And you should listen to it.

The way that I sometimes explain this to students is it’s sort of like exercise. If there’s a little bit of burn, then you know you’re doing it right. But if it’s painful, you need to stop. That means you’re doing something that’s not good for your body.

Sometimes it’s just a matter of kind of figuring out, well, what experience or what thing do you want to write about that you’ve got a little distance from, you have a little perspective, you can approach it from different vantage points? That can be a really good topic to start writing about in the style that I teach in this book.

The research that’s been done on these sorts of practices, it points to a lot of different results and a lot of maybe potential causes for why writing can be so helpful. But some of the leading theories, if you will, show that by writing a story, you’re bringing coherence to it. You’re wrapping your arms around something that seemed fragmented or sort of discombobulated even.

And that there’s a real pleasure and a real benefit to being able to articulate something in a coherent way. Our brains want to do that, naturally. And sometimes trauma impacts the brain’s ability to do that. And so, forcing yourself to wrap your arms around it can be really, really helpful.

I think it was Joan Didion, who said, ‘I need to write to understand what I think about something.’ I know that’s true for me as well, that sitting down to write a story helps me work through, ‘What do I really think about that? And how did I feel at that moment? And why was I feeling that way? Did it have something to do with the relationship that I had with that person? Is there something unexplored that I haven’t thought about and maybe I need to start thinking about.’

It’s using writing almost as a way to get ideas out onto the page and, again, to make sense of it.

And then there’s just the idea, and I think this is true, as well of unloading that emotional burden onto the page, even if it’s momentary.

I know when I write something down, whether it’s in a Word document or in a journal, I know it’s there and I know I don’t have to constantly be thinking about it anymore or trying to remind myself of it. So I think there’s a psychic weight loss that also happens with this kind of writing.

Joanna: I totally agree with you. And as you were talking now, I think there’s often a mode of a person’s preferred expression. And obviously, you’re a writer. I’m a writer, people listening are generally writers, as this is a podcast for writers, but I feel like sometimes people say, ‘You could go to therapy.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, do you know what, I don’t really talk my issues. I write my issues.’

My first husband, this was over a decade ago… I’m happily in my second marriage now. But my first husband left me and I have a whole load of journals from that time. And I read them and I don’t even recognize the person in those journals. As you say, it all comes out on the page.

It was about a year, I closed the last book on that and it doesn’t hurt now to look back. And yet when I open one of those journals, I’m like, ‘Whoa, who is that person?’ So writing this down and I haven’t published any of those, by the way, they were just journals but it is almost a preferred mode. If someone wants to talk or someone wants to create art, or someone wants to dance, or however you express your feelings and work through that, and for some people it’s writing.

David: I think that’s totally true. I’m curious when you go back and read some of those things, do you feel very differently than the feelings that you put on the page or are those still kind of close anyway?

Joanna: No, they’re like another person. As in I read them, I can see it’s my handwriting, but I can’t even access all the kind of self-destructive stuff and that, say, hate and things, terrible poetry, all the things that I wrote down, then, it’s almost like I exorcised it onto the page.

By putting it there, it exists there, not in my head. I feel like it was very healing for me to do that. And of course divorce is an incredibly common thing. But my parents got divorced and I feel that they were traumatized by that experience.

Where I don’t feel I’m traumatized because I almost dealt with it by writing, which is why it’s so powerful.

David: That’s so interesting. I feel very similar, when I go back to read things, I have that thought of, ‘Who was I when I was feeling this way?’ I had a therapist once who told me about this mental trick, I guess you could call it.

She called it the fives or the five questions or something like that, where she said, ‘When you’re feeling these really intense feelings, ask yourself, ‘Is this going to matter in five minutes? Is it going to matter in five hours? Is it going to matter in five days,’ right, and you just keep going, maybe five years is where you cut it off.’

That can sometimes give you enough perspective to say, ‘Okay, I had a really, really bad morning, but this probably isn’t going to matter in a few days.’ And just to get that perspective. Sometimes I think it’s helpful to do that with the subject matter of the things I want to write about is this something that is still affecting me more than five years after it happened? That might be an indication that I need to work through it, right, that it’s big enough, it has enough of an effect on my day-to-day life that I haven’t buried it, I haven’t made sense to that, I haven’t wrapped my arms around it.

Whereas, when you’re in that moment and you’re thinking, ‘All this rage is pouring out onto the page and this feels so good. And someone should read this.’ Are you sure that you’re going to want someone to be able to read that five years from now?

Angie Ricketts wrote the afterword for my book. This is something her and I talk about all the time, that her memoir, she sold a proposal for the memoir and the publisher had it in their mind that this book had to come out at a very, very specific time to kind of hit the book club, list creation time. And there was also a TV show that was very popular that was related to the same topic, and we wanted to have that available at the same time.

So she ended up having to write the memoir in three months. And she spent the first two months panicking about it. And then finally, in the last month, really sat down to write it. Her memoir is written in present tense because she had all the journals and the diaries from all the years that she was writing about.

The book has this immediacy to it and it’s unfolding before your face to impact on the reader. And now, when we talk, she says the same thing you did, ‘I read that, and I don’t even know who that person was.’

I asked her a similar question, ‘Do you wish you maybe wouldn’t have put it out into the world?’ And she said, ‘No, absolutely not,’ because what that book does is it gives this snapshot of who she was as a person at that time. And the fact that she doesn’t feel like that person anymore, is a sign that the writing did something for her.

It helped her get past some of those things and look at them in a different way. And she also said there are things in her book that maybe she would rewrite now, if she was doing a second edition or something. She said lots of people were frustrated or upset about things that she wrote, but that no one called her a liar. And that was the definition of success for her at that time was to just get it out onto the page. But now, if she sat down to write, it would be a very different book.

Joanna: You’re going to have to tell us the name of that book now.

David: Angie’s book is called No Man’s War. And Angie was married to an army officer who deployed I believe it was nine times to Iraq and Afghanistan. And so the book is about her life as an army wife.

Joanna: You mentioned the word liar there.

Truth and lies and something in between, I feel is very difficult in memoir or as you said, personal essay because our memories are attached to emotions.

We experience something from our perspective. I completely appreciate that my own journals about my divorce are not my ex-husband’s perspective. But this is a question that I keep coming back to.

Just so you know, I’ve written over 30 books now, none of them are memoir. I have a memoir in progress. So I think about this a lot. How can we even tell or can we write things that serve the story beneath the story, as you call it? Does everything need to be factually true?

David: So this is where my journalism friends will probably disagree with me but my memoir and personal essay friends will agree.

I think the premise itself is probably not exactly accurate. I’m not convinced that I can write a totally objective, factually correct story. I just don’t know that my human brain is capable of doing that because like you said, when we remember things, there are emotions tied to it.

There are also ways that our body copes with traumatic experiences that results in memories being stored in weird ways and fragmentation. And there’s just tons of things that happen in the brain during a traumatic experience, that, I think having the standard of, I’m going to write something that is objectively fact-based and evidence-based and true, is maybe just something that’s not possible with this kind of writing.

Now, I think that there’s a freedom and kind of a beauty in recognizing that and leaning into it for lack of a better phrase. So when I write, I try to be very transparent about whether this is something I remembered, whether this was something based on evidence or based on a document or based on a letter, for example, or if this is something I had recorded or had preserved in some other way.

I try to be transparent about where the information is coming from and also being careful not to put emotions onto other people or to try to speculate about what they are thinking or feeling unless there’s a point to me speculating, to maybe show the reader that I can’t read this situation. I’m not sure if this person is feeling this or feeling that, and giving the reader an opportunity to collect the evidence themselves and maybe come to their own conclusion.

It’s not fun, I don’t think for the average reader to be told everything constantly. It’s also, I think, pleasurable, frankly, to read something and know that the author is trusting you to come to your own conclusion or is okay with you bringing yourself to the story and making sense of it in your own way.

Now, if I am writing a scene, let’s say, and I have no documentation except my memory, I’m going to be really clear about that.

If it’s something that I think happened or that I’m pretty sure happened or I know it happened, but I don’t know the details of it, that’s when I might start looking for corroborating evidence.

Can I find a picture of the setting where this happened? That’s from that period. Can I say something factual about what things look like there? Can I find information? Let’s say the scene is across the street from an ice cream shop, can I then say, ”Well, it smelled like waffle cone.’ I better make sure that that place sells waffle cones.

There’s this kind of detective or investigative work that I actually find quite enjoyable as a writer, where I’m searching for those sensory details and I’m searching for the essence of a place or of a person. What can we infer from someone’s letters, for example, about how they felt or about who they were?

We can make those inferences and we can make those speculations but we also want to show, I think, where the evidence comes from and how we got to that conclusion, again, to show that we’re not just making stuff up. But I think that the key is transparency and then also thinking about, well, if I wanted to write the scene, what details would I need and how can I find those?

Joanna: It’s interesting because as part of writing novels, sensory detail is so critical for getting deep into a character’s point of view. And you talk about this in the book is turning ourselves into a character in a story but this is so difficult in terms of this is me. Yes, you could write in first person, like, I think you mentioned your friend did. But even if you do, you still have to almost create the character that is you at whatever point in your life you’re writing about. How can we do this?

What are your tips for separating ourselves enough and how would we tell the story with this character?

David: I’ll say two things. So the first is, I am sure you picked up on this in my own writing, but I’m pretty honest about my own failings, and my own shortcomings, and character flaws, and even times where I regret how something happened, I regret my behavior, I try to be as honest as I can about what happened, not in a defensive way, but in a descriptive way of showing that I’m not that reliable of a narrator in most cases.

I think a reader really appreciates seeing a narrator as flawed, that this isn’t a book of here are all the ways that I’m so smart and smarter than you, and you should listen to me. It’s about, I’ve made these mistakes too or these things have happened to me too, or I had this bad reaction in this situation.

So that’s the first thing I think is it’s important to present yourself as a three-dimensional human, flawed, wonderful, beautiful, sometimes ugly person. And giving that same kind of grace and that same perspective to the other characters in your book as well.

I have this good writing friend of mine who said you don’t have to call someone a jerk in your writing. You can just describe what they do. And if that is how a jerk behaves, your reader will come to that conclusion. You don’t have to tell them someone is a jerk.

And at the same time presenting yourself, like I said, as someone who can do no wrong is not really that interesting, I don’t think. I like to see when people roll up their sleeves and say, ‘Here’s my scar and here’s how I got it.” Now, so that’s the first thing.

Second thing is I’m an outline writer. That’s how my brain works. That’s how I have to do it. I know that’s not true for everyone. So if you’re a writer who writes by the seat of your pants, this might sound really awful. But for the outlining folks I try to first understand the action in a story in a paragraph.

So, this is how the story starts, here are the ways that the tension builds, this is the big crisis moment, here’s how things get resolved. I want to have that understanding of a story before I start writing.

Then the next step is okay, well, I have to show either myself or I have to show other people acting in the story. What are the things that the reader is going to want to know or that they need to know about those characters to make sense of what’s happening in the story or to make sense of the action that the character takes?

The example I use in the book is a friend of mine wrote a book about a trip that I went on with him. And in the first few pages of the chapter where he introduces me, he mentions my weight three separate times. I played football in college. I’m a bigger guy. I’m 6’4′, about 250-some pounds. And he makes this comment about three different times in the beginning of the chapter. And when I read it, I thought, ‘Why is he doing this? I am more than just my body weight.’

Then, towards the end of the chapter, he has this climactic scene where we’re in the middle of this really terrible storm that could have really ended the trip. I had to drag our canoe that was full of supplies, about 500 pounds worth of supplies. I had to pull it straight up the side of a hill.

And so when I asked him, ‘Why did you keep bringing up my weight?’ He said, ‘I wanted people to believe that you could actually do that, that you could pull this canoe up the side of a hill. And I felt like if I didn’t stress that you’re a big strong guy, then people wouldn’t believe it or they would doubt my claim.’

So it’s sort of almost like reverse engineering.

I want to show how this person acted. Why do I think they did that and what are the details that I can present about them? What are the little vignettes that I can present? What are the anecdotes that maybe will help explain this behavior just a little bit to the reader?

That’s where I’m going to start, is figuring out what are those little quirks, those little things about the character, that you can see this when you’re a seasoned storyteller. You see this in movies and TV and stories where you learn this detail about someone and you think, ‘Oh, this is going to come back? This is going to come back at some point.’ This is a clue of how they’re going to behave later.

Those are the sorts of things I look for. And then it’s a matter of making sure that character, whether it’s yourself or someone else is a real like three-dimensional character and that they’re not all good. They’re not all bad. And there are a bunch of stuff in between.

Joanna: This is what’s so hard, I think, with memoir and story because when I create a novel, and I’m a discovery writer, by the way. I prefer the term discovery writer.

David: Oh, I like that. Going to use that now.

Joanna: Yes, definitely use it. We’re trying to change the language away from seat of the pants or pantser, which is just such a terrible word and very American, because, of course, pants is underwear here in England.

David: Oh, okay. Well, that makes sense.

Joanna: When I write a novel, I create a character that fits my plot or my narrative, why did this bad person do the bad thing, like, blow up the world or whatever? And it’s easy to choose the vignette to support my story.

But you’re talking there about, you mentioned grace for the other characters, but we can’t write three-dimensional characters for everyone in this book. So, for example, your example with your weight or your build in your friend’s book, it wasn’t about you. The book wasn’t about you. So that was one detail that didn’t encapsulate your entire self.

Now, one of the things I get a lot of emails from people writing memoir, people worried about either getting sued if they’ve written something that could be taken the wrong way by people in a serious way or just damaging friendships or relationships by taking a particular point of view.

Let’s say you were actually offended about comments about your size and then you just didn’t talk to that friend anymore, or whatever. So you can see, especially in these times where people get quite wound up on social media.

What are your thoughts on the concern of offending people or getting sued, and how do we portray other characters, especially with trauma, because these are going to be difficult relationships?

David: I struggle with this. I don’t want to present myself as the expert who’s got it all figured out. But I can share maybe some of the influences that I think about.

There’s this great American writer named William Zinsser, who wrote a book called On Writing Well, and he makes this point about memoir where he says, let’s say you write your story and your sister gets really upset about it, you can tell her that she can write her own memoir if she doesn’t like it. So there’s that kind of this is my story and I don’t care what you think about it sort of approach.

That feels to my Midwestern sensibilities, that feels like really aggressive and mean. The other side of the spectrum is only writing things that people find flattering or that they would be happy or at least not upset about the world knowing. And I do think that there are times in which it does pay to give that kind of deference to a character.

For example, when I’m doing a more journalistic piece and I’m writing about someone and I am not a character in the piece, this is a story completely about them, I will run the story by them. I won’t send them the story so that they can read it word for word. I will read it to them either on Zoom or on a phone. And I’ll read the details that are about them.

I always say, the reason I’m calling here is because I want to make sure that there’s nothing factually inaccurate about what I’m saying. But at the same time, I want you to know that I get to decide how this affects the story. So if I then started saying, ‘Okay, here’s this scene where I talk about how you did X,’ and the person might say, ‘Well, that’s not exactly how I felt. What I really thought was this.’

That might be something I definitely want to change that because I don’t want to mischaracterize how they felt. Now, if I make a judgment about the person, and they say, ‘Well, I don’t like that judgment,’ then that means not something I will change unless they can give me information that would change my mind about the judgment.

Now, when I’m writing about myself and there are other characters in the book or in the story that I’m related to, or that I’m friends with, or that I teach, or whatever the relationship is, I always try to make sure that the story is from my perspective, that I’m not trying to tell their story in my story. I want to present things from my vantage point, from my perspective.

From there, I want to try to figure out what were they thinking? What were they feeling? I think the only way to really do that, if the person’s living, of course, is to interview them and to ask those questions. I’ve done that with several members of my family. There are lots of stories in the book from my family. I had questions and I asked for answers, and I probed for details. I asked them to describe things.

That became my evidence for the thing that I wrote. Now, I know that there are big differences in libel laws between the UK and the U.S., I want to say that that’s much more of a concern in the UK. I don’t want to advise anyone on legal precedent for what they can say, but I try to use that that criteria that Angie told me about, which is someone might be upset with me, but as long as they don’t think I lied, that’s the thing that I’m looking for.

Then the other question you have to ask is how important is the relationship to you?

There are, I think, reasons to write about people in a way where it’s like, ‘Well, if you wanted me to write a better story about you, you should have treated me better.’ If you wanted to be the hero in my story, then you should have been the hero in my story.

I would never suggest that someone should gloss over or sugarcoat someone’s flaws, just because that would upset them. Because at the end of the day, it’s really your story and you trying to understand what you went through, and then trying to communicate that with other people so that they can understand too.

And like I said, if you present a character for who they are, the reader will come to that conclusion on their own. And it will feel more natural and less of an attack. And, for lack of a better word, it’s sort of like, well, this is what happened and this is how I felt about it.

There are times then where you might want to incorporate what other people were thinking and feeling, and times when you might not want to. And that’s really, totally up to the writer to make that decision.

I don’t necessarily have rules that I follow, but I try to listen to the feeling I get when I’m writing something. And if I start to feel like, oh, they’re not going to like this, then I want to interrogate that. Why aren’t they going to like it? Is it because I’m being too harsh or is it because this is really embarrassing for them and they know it? Okay, well, if it’s really embarrassing for them and they know it, and they’ve tried to make amends or apologize, how can I put that into the story or how can I give this context that would leave a reader thinking, ‘Wow, that was a really difficult situation, but it sounds like they’re in a better place?’

If that’s the case. If it’s not, don’t invent that, right? Don’t try to invent a resolution when there isn’t one. Sometimes stories don’t really end. Another story begins.

Joanna: Yeah, absolutely. And memoir never ends, I think until we’re dead.

David: For sure.

Joanna: There’s always another book. So that was fantastic.

David, tell us where people can find you and your book and everything you do online.

David: Thank you so much. I have a website, davidchrisinger.com. You can find all my latest stuff there, upcoming events, other books I’ve written articles, what have you.

In terms of buying the book, obviously, there’s Amazon. In the United States, indiebound.com is a great resource as well. You can buy books from your local bookstores. I’m not sure who to point you to in the UK, but the publisher is Johns Hopkins University Press. I think that’s the best way to find it.

Joanna: Brilliant. Thanks so much for your time, David. That was great.

David: All right. Thank you.

The post Stories Are What Save Us: Writing About Trauma With David Chrisinger first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn