As writers, teachers, publishers, booksellers, and librarians in our local, national, and international communities grapple with how to proceed in their creative, financial, professional, and personal lives during this time of uncertainty, we are compiling a list of resources we hope you will find useful. We will be updating this list as we learn of new resources and opportunities. (If you know about an opportunity, initiative, or helpful resource not on this list, please send an e-mail to editor@pw.org.)

Financial Resources

The Academy of American Poets, the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses, and the National Book Foundation have established the Literary Arts Emergency Fund to help writing organizations outlast the coronavirus pandemic. With the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the three nonprofits will administer a total of $3.5 million via one-time grants of $5,000 to $50,000. Applications were accepted through August 7.

The Poets & Writers COVID-19 Relief Fund provides emergency assistance to writers having difficulty meeting their basic needs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the initial round of funding, Poets & Writers distributed 107 grants of $1,000 each to writers from twenty-six states. A second round of funding, in which the organization expects to be able to distribute grants of $1,000 to approximately thirty writers, closed on June 28.

The initiative Artists Relief, sponsored by a coalition of arts grantmakers—the Academy of American Poets, Artadia, Creative Capital, Foundation for Contemporary Arts, MAP Fund, National YoungArts Foundation, and United States Artists—will award a total of $10 million, half of which was contributed by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, to artists and writers “facing dire financial emergencies due to the impact of COVID-19.” Applicants who are twenty-one or older, able to receive taxable income in the United States regardless of their citizenship status, and have lived and worked primarily in the United States over the last two years are eligible to apply for $5,000 grants. Artists Relief will also serve as an informational resource, and will collaborate with Americans for the Arts to launch the “COVID-19 Impact Survey for Artists and Creative Workers.”

The Writers Emergency Assistance Fund, sponsored by the American Society of Journalists and Authors (ASJA), helps established freelance writers “who cannot work because they are currently ill or caring for someone who is ill.” Applicants need not be members of the ASJA but must have five published articles from regional or national publications or one book published by a major publishing house.

Authors League Fund offers assistance to professional authors, journalists, and poets who “find themselves in financial need because of medical or health-related problems, temporary loss of income, or other misfortune.”

Carnegie Fund for Authors awards “grants to published authors who are in need of emergency financial assistance as a result of illness or injury to self, spouse, or dependent child, or who has had some other misfortune that has placed the applicant in pressing and substantial pecuniary need.”

The PEN America Writers’ Emergency Fund distributes grants of $500 to $1,000 to U.S.-based professional writers, including fiction and nonfiction authors, poets, playwrights, screenwriters, translators, and journalists, who demonstrate an acute financial need, especially one resulting from the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Artist Relief Tree is “set up to collect donations from those of us with the means to help. We intend to support artists, particularly freelance artists, in a small way. Unfortunately we cannot hope to replace artists’ entire fees or lost work, but we wish to provide hope, make a small difference, and show solidarity with colleagues and Friends.” A group of artists—Andrew Crooks, Marco Cammarota, Morgan Brophy, Rachel Stanton, Tehvon Fowler-Chapman, and Thomas Morris—organized the fund. Note: This group is not taking new requests for funds at the moment.

Queer Writers of Color Relief Fund, started by Luther Hughes, founder of Shade Literary Arts, seeks to “help at least 100 queer writers of color who have been financially impacted by the current COVID-19. Priority will be given to queer trans women of color and queer disabled writers of color, but I hope this relief fund will help as many queer writers of color as it can.”

The Creator Fund, from the e-mail marketing company ConvertKit, is offering financial assistance of up to $500 for artists and small business owners—the term “creator” is loosely defined. The mini-grants can be used for groceries, childcare, rent, mortgage or medical expenses. The Fund, which will disburse $185,300 in total, is now closed to new applications after receiving more than sixteen thousand applications.

The Dramatist Guild Foundation’s Emergency Grants are available to “individual playwrights, composers, lyricists, and book writers in dire need of funds due to severe hardship or unexpected illness.” The grants, which typically range between $500 and $3,000, are intended to support expenses related to healthcare, childcare, housing, disability, natural disaster relief, and other unforeseen circumstances. Applicants will be notified in two to four weeks.

Substack, an e-mail newsletter platform, will administer a total of $100,000 to individuals “writing, or thinking about writing, on Substack” through its Independent Writer Grant Program. Individuals who are experiencing economic hardship due to the coronavirus pandemic can apply for grants from $500 to $5,000, in addition to mentorship from the Substack team. Applications are open through April 7. (It is free to join Substack and start an e-mail newsletter; if you decide to charge your audience a subscription fee, Substack takes 10 percent.)

The Freelancers Relief Fund, organized by the Freelancers Union, will offer “financial assistance of up to $1,000 per freelance household to cover lost income and essential expenses not covered by government relief programs” including food supplies, utility payments, and cash assistance to cover lost income. Freelancers who reside in the United States, derive most of their income from freelance work, and have experienced “a sudden decrease of at least 50 percent of income as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic” are eligible. Applications have been temporarily closed due to the overwhelming response the fund received from its community.

We Need Diverse Books (WNDB) will administer emergency grants of $500 through the WNDB Emergency Fund for Diverse Creatives in Children’s Publishing to “diverse authors, illustrators, and publishing professionals who are experiencing dire financial need.” Traditionally published writers and illustrators who have lost income due to canceled festival, school, or library visits, are eligible, as are furloughed publishing professionals—editors, agents, publicists, designers, and sales positions—who work in the field of children’s literature. Only U.S. residents are eligible. Applicants should receive a response in two to three weeks.

The Maurice Sendak Foundation has dedicated $100,000 to the new Maurice Sendak Emergency Relief Fund, which will be administered by the New York Foundation for the Arts. The fund will offer grants of up to $2,500 to children’s picture book artists and writers who “have experienced financial hardship from loss of income as a direct result of the [COVID-19] crisis.” Children’s picture book artists and/or writers who have published at least one picture book in the last five years and are residents of the United States or U.S. territories are eligible. Applications will open on April 23 and close after six hundred applications are received; grantees will be notified by May 15.

As part of its response to the COVID-19 crisis, the Economic Hardship Reporting Project (EHRP) offers emergency hardship grants of $500 to $1,500 to professional journalists based in the United States. EHRP will prioritize the unemployed, single parents, members of one-income families with young children, and people with acute medical needs over the age of fifty-five. Applications are reviewed on an ongoing basis. EHRP also accepts pitches from independent journalists for stories on “the intersection of the coronavirus and financial suffering in America, with an emphasis on writers and photographers who are themselves experiencing significant economic hardship caused by the pandemic.” EHRP typically pays reporters roughly a dollar a word or $300 to $500 a day for photojournalists.

The Foundation for Contemporary Arts (FCA) has established a temporary Emergency Grants COVID-19 Fund to “meet the needs of experimental artists who have been impacted by the economic fallout from postponed or canceled performances and exhibitions.” Individual artists who make “work of a contemporary, experimental nature,” live in the United States or U.S. territories, and have a U.S. Tax ID number are eligible to apply for grants of $1,500. FCA supports artists working in poetry, dance, music/sound, performance art/theater, and the visual arts. Applications are open through May 31.

Location-Specific Financial Resources

The California Relief Fund for Artists and Cultural Practitioners program, created by the California Arts Council in response to the economic crisis and impending financial needs of individual artists resulting from the coronavirus pandemic, will award a total of $920,000 via unrestricted $1,000 rapid-relief grants to more than 900 individual artists and cultural practitioners in the state of California. “Grants will be distributed to reflect the cultural and geographic diversity of the state of California—including those who are of historically underserved communities who are especially vulnerable financially due to this economic crisis.” Applicants must be current, full-time residents of the state of California, artists or cultural practitioners; and must not be eligible for or currently receiving traditional California state unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. The application deadline is August 18 at 3 PM PDT.

Literary Arts in Portland, Oregon, has created the Booth Emergency Fund for Writers “to provide meaningful financial relief to Oregon’s writers, including cartoonists, spoken word poets, and playwrights.” Awards of $1,000 each will be given to 100 writers at the end of the application period, which runs through May 13. (If additional funds are secured for this purpose, Literary Arts may open up a second round of applications later in June.) Since COVID-19 is disproportionately impacting communities of color, Literary Arts is prioritizing funding “for writers identifying as Black, Indigenous, and/or People of Color.” Funds are intended to be used for (but are not limited to) recouping financial losses due to canceled events, offsetting loss of income for teachers, and support for artists working full- or part-time in the service industry “or other professions who have lost income.”

The Boston Artist Relief Fund “will award grants of $500 and $1,000 to individual artists who live in Boston whose creative practices and incomes are being adversely impacted by Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19).”

The Oregon Science Fiction Convention’s Clayton Memorial Medical Fund helps professional science fiction, fantasy, horror, and mystery writers living in the Pacific Northwest states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Alaska deal with the financial burden of medical expenses.

NC Artists Relief Fund, sponsored by Artspace, PineCone, United Arts Council, and VAE Raleigh, supports “creative individuals who have been financially impacted by gig cancellations due to the outbreak of COVID-19.” All donated funds “will go directly to artists and arts presenters in North Carolina. Musicians, visual artists, actors, DJ’s, dancers, teaching artists, filmmakers, comedians, and other creative individuals and arts presenters are experiencing widespread cancellations due to this global pandemic.”

The Safety Net Fund is offering financial support to artists who typically make their living offline, at in-person events and performances. To qualify, you must reside in the Bay Area (or near it, as some San Joaquin and Santa Cruz county zip codes are eligible), provide proof of an artistic endeavor in the last six months, cannot be eligible for unemployment insurance from the state, and must have earned less than $1,000 of income in the last thirty days.

The San Francisco Arts & Artists Relief Fund, cosponsored by the Center for Cultural Innovation, San Francisco Arts Commission, and Grants for the Arts, offers funds to “mitigate COVID-19 related financial losses that artists and small to mid-sized arts and culture organizations have suffered.” Individuals based in San Francisco who are eligible for, or currently on employment, are eligible for grants of up to $2,000. Organizations that conduct a majority of their work in San Francisco and operate on a budget of less than $2 million are eligible for grants of up to $25,000.

The Personal Emergency Relief Fund, sponsored by Springboard for the Arts, helps artists in Minnesota “recover from personal emergencies by helping pay an unanticipated, emergency expense.” Artists can request up to $500 for lost income “due to the cancellation of a specific, scheduled gig or opportunity (i.e. commissions, performances, contracts) due to coronavirus/COVID-19 precautionary measures.”

Max Kansas City’s Emergency Grants offers grants of up to $1,000 to New York State residents who are professionals in the creative arts. “Individuals who have made their living through their art form either professionally or personally and demonstrate a financial need for medical aid, legal aid, or housing” are eligible.

The NYC Low-Income Artist/Freelancer Relief Fund, organized by Shawn Escarciga and Nadia Tykulsker, offers grants of up to $150 to “low-income, BIPOC, trans/GNC/NB/Queer artists and freelancers whose livelihoods are being affected by this pandemic in NYC.”

The New Orleans Business Alliance’s Relief Fund offers grants of $500 to $1,000 to “meet the needs of gig economy workers who have been directly impacted via loss of income.” Writers who live in New Orleans, earn more than 60 percent of their income via gig-work, and are below a certain income level are eligible.

Artist Trust’s COVID-19 Artist Trust Relief Fund offers grants of $500 to $5,000 to “artists whose livelihoods have been impacted by COVID-19” and are residents of Washington State. The grants are intended to help artists who are coping with lost wages and earnings, lost income from canceled events and performances, medical expenses, rent and mortgage payments, food, utilities, and other living expenses.

The Indy Arts & Culture COVID-19 Emergency Relief Fund, sponsored by a coalition of community funders and the Arts Council of Indianapolis, offers $500 grants to “individuals working in the arts sector and impacted by the current public health crisis,” especially those working at small to mid-sized nonprofit arts and cultural organizations. Applicants must live in Marion or one of the seven surrounding counties in Indiana.

The Cultural Relief Fund offers grants of up to $2,000 to individuals in the Seattle area for “emergencies related to the COVID-19 virus and to support the creative responses cultural workers offer in times of crisis.” The first round of funding was available April 1 through May 15. Applications are reviewed weekly; applicants will be notified within ten business days.

The Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council Emergency Fund for Artists offers grants of up to $500 to artists dealing with financial losses due to canceled events, canceled classes, or school closures. Artists who live in Pittsburgh (in Allegheny, Beaver, Butler, Washington, Lawrence, Indiana, Greene, Fayette, Washington, and Westmoreland counties) are eligible. Applications are reviewed on a rolling basis.

The Canadian Writers’ Emergency Relief Fund, financed by the Writers’ Trust of Canada, the Writers’ Union of Canada (TWUC), and the Royal Bank of Canada, will distribute $150,000 to writers in Canada that have “seen contracted or projected income evaporate due to the current public health crisis.” Poets, fiction writers, nonfiction writers, and young adult writers with a track record of publication (or self-published writers who are members of TWUC) who will lose more than $1,500 between March and May 2020 are eligible to apply for grants of $1,500. The application deadline was April 9.

The Atlanta Artist Lost Gig Fund, administered by the arts nonprofit C4 Atlanta, offers grants of up to $500 to artists in the Atlanta area who “have unmet essential needs due to lost revenue from canceled upcoming events and gigs.” Artists who make their living from their practice are eligible.

The Culture Connects Coalition Artist Relief Fund, cosponsored by the City of Santa Fe Arts and Culture Department and the Lannan Foundation, will administer grants of $500 to artists who live in Santa Fe County and have suffered financial losses due to canceled events, including readings, panels, and teaching opportunities. Priority will be given to requests from Black/Indigenous/People of Color, transgender and nonbinary artists, and/or artists with disabilities. The current round of applications is open until May 17; the next round of applications will open on June 1.

Resources for Working Remotely

Zoom: “How do I host a video meeting?”

Vimeo: “How to plan a virtual event: Vimeo’s live production experts tell all”

Creative Capital: “Thinking About Livestreaming as an Artist? Read This First.” Artists Yara Travieso and Brighid Greene describe how to approach livestreaming and survey platforms available to writers: Instagram, HowIRound, Vimeo, Twitch, YouTube, Facebook, and Zoom.

The Chronicle of Higher Education offers advice for teaching during the coronavirus, including Moving Online Now: How to Keep Teaching During Coronavirus, a collection of articles, advice, and opinion pieces on online learning; “The Quandary: How Do I Support a Student Who’s Sick With Covid-19?”; “Eight Ways to Be More Inclusive in Your Zoom Teaching”; and more.

The National Endowment for the Arts has put together a list of ways to create an inclusive experience for virtual and digital events. “Resources to Help Ensure Accessibility of Your Virtual Events for People with Disabilities” includes information about captioning, sign language interpretation, virtual platform accessibility features, and more.

Resources for Booksellers

The American Booksellers Association’s Coronavirus Resources for Booksellers includes immediate steps to take during the outbreak, ABA initiatives during the outbreak, and opportunities for financial assistance.

Book Industry Charitable Foundation (Binc) offers assistance “for the medical expenses of booksellers and to help booksellers in specific cases where store closure and/or loss of scheduled pay leads to the inability to pay essential household bills for an individual or family.”

The #SaveIndieBookstores campaign fund—organized by James Patterson, Reese’s Book Club, the ABA, and Binc—will administer financial assistance to independent bookstores, “the hearts and souls of main streets in cities and towns all across the United States.” Applications will be open from April 10 to April 27.

Resources for Librarians

The Help a Library Worker Out (HALO) Fund, organized by the nonprofit EveryLibrary Institute, will administer grants of up to $250 to library workers, librarians, and library staff who are “experiencing personal or household financial difficulties during this time of crisis.” Individuals who reside in the United States or U.S. territories and have lost work or experienced a significant wage reduction—or are part of a household in which a member has lost their job or seen their income reduced—are eligible. HALO grants can be used toward personal expenses such as food, rent or mortgage payments, cell phone and internet expenses, medicine, or household needs. Grants are made on a rolling basis.

The American Library Association’s (ALA) Pandemic Preparedness page includes news on how librarians are dealing with the pandemic, professional development and training resources, and lists of federal, state, and local resources. The ALA also hosts free webinars on topics such as considering copyright during a crisis, navigating the impact of COVID-19 on library technical services, using a library’s virtual presence to reach users with disabilities, and more.

Resources for Readers and Writers

The New York Public Library is offering expanded access to its online research databases. Research librarians and curators are also available for online consultations.

Audible has assembled a free collection of audiobooks, including literary classics and books for young readers.

Many university presses and other not-for-profit publishers are collaborating with Project MUSE to offer free access to books and journals.

Independent publisher Archipelago Books is unlocking access to thirty e-books through April 2.

As usual, the Academy of American Poets and the Poetry Foundation, among other organizations, offer free-to-access poetry archives.

The editors at Brightly, a subsidiary of Penguin Random House, have assembled “Reading Through It Together,” a set of educational resources and reading exercises for children and teens.

In partnership with Simon & Schuster, the Folger Shakespeare Library is sharing resources from its video and audio recordings archive—including footage of the Folger Theatre’s 2008 production of MacBeth—through July 1.

The Sequential Artists Workshop (SAW) in Gainesville, Florida, is making five of its most popular online courses in comics and graphic storytelling available for free.

Calamari Press has made digital copies of all its book titles, as well as back issues of Sleepingfish literary magazine, available for free.

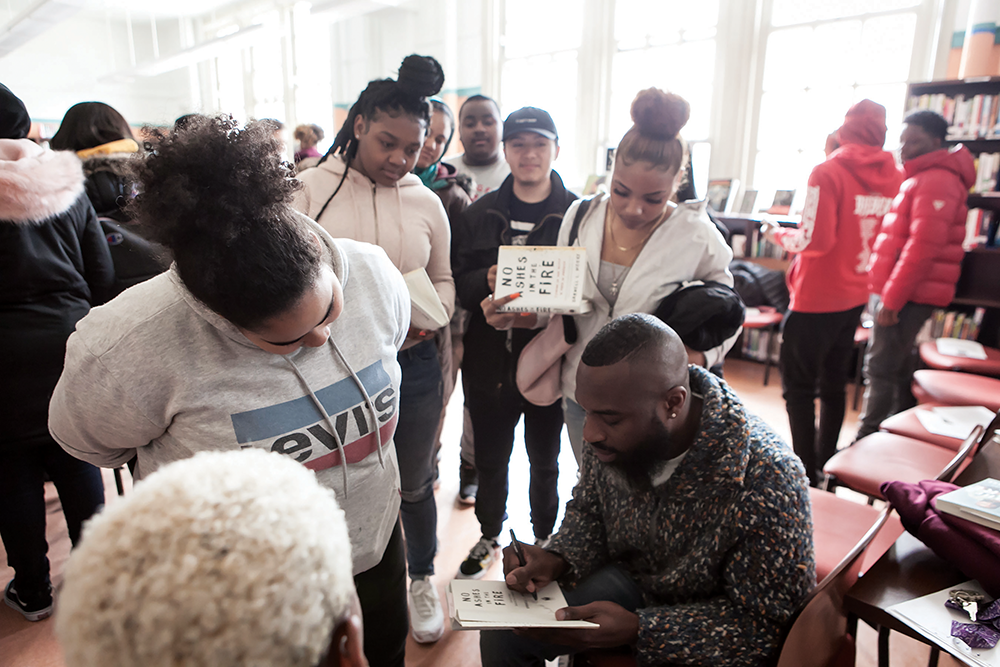

Writer Suleika Jaouad has organized a daily creativity project, the Isolation Journals, through which she sends daily journaling prompts via e-mail from some of her favorite writers, artists, and musicians, including Elizabeth Gilbert, Erin Khar, Esmé Weijun Wang, Georgia Clark, Hallie Goodman, Ilya Kaminsky, Jen Pastiloff, Jon Batiste, Jordan Kisner, Kiese Laymon, Lily Brooks-Dalton, Mari Andrew, Melissa Febos, Nora McInerney, Rachel Cargle, Ruthie Lindsey, and more.

The Authors Guild posted their webinar “Coronavirus Relief Programs for Authors and Freelancers,” featuring Mary Rasenberger and Umair Kazi, the Authors Guild’s executive director and director of policy and advocacy, respectively, and Marcum LLP partner Robert Pesce. The trio covers “how authors and freelancers can benefit from the government relief programs for economic assistance during the coronavirus crisis.” They discuss qualification criteria for unemployment, loan terms, and other information about the process.

As usual, Poets & Writers offers weekly writing inspiration through The Time Is Now, which features writing prompts in poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, and Writers Recommend, through which authors share the rituals, art, books, music, movies, and habits that get them writing.

Other Resources

NYC Covid Care, a volunteer network of more than 2,500 mental health professionals, life coaches, spiritual care providers, organizers, and crisis line operators based in New York City, offers free support to those in crisis. All essential workers and their families based in the New York City Metro Area are eligible to participate. Applicants will be contacted by a volunteer professional via phone or video-conference for a confidential consultation.

COVID-19 Freelance Artists Resources is “an aggregated list of FREE resources, opportunities, and financial relief options available to artists of all disciplines.”

Creative Capital’s List of Arts Resources During the COVID-19 Outbreak

Kickstarter’s COVID-19 Coronavirus Artist Resources

New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) Emergency Grants Page

BOMB magazine’s COVID-19 Artist Resources and Closing the Distance: New Spaces for Community, an “ongoing list of online tools, workshops, and livestreams to keep you company and engaged in the time of COVID-19.”

National Endowment for the Arts COVID-19 Resources for Artists and Arts Organizations

Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts has compiled a national directory of organizations that offer legal services to artists, some of which are provided pro bono. Membership and processing fees vary by organization.

The Community of Literary Magazines and Presses COVID-19 Resources for Indie Publishers lists emergency grants and resources available to independent publishers and other literary stakeholders.

Just Shelter, a project started by Evicted author Matthew Desmond and Tessa Lowinske Desmond, offers a state-by-state directory of more than six hundred organizations that work to “preserve affordable housing, prevent eviction, and reduce family homelessness.”

The Authors Guild posted its webinar “Coronavirus Relief Programs for Authors and Freelancers,” featuring Mary Rasenberger and Umair Kazi, the Authors Guild’s executive director and director of policy and advocacy, respectively, and Marcum LLP partner Robert Pesce. The trio covers “how authors and freelancers can benefit from the government relief programs for economic assistance during the coronavirus crisis.” They discuss qualification criteria for unemployment, loan terms, and other information about the process.

The Whiting Foundation offers notes from financial guru and artist Amy Smith’s April webinars “Unemployment Compensation for Freelancers and Self-Employed Individuals,” “Applying for PPP and EIDL Relief as an Organization,” and “Applying for PPP and EIDL Relief as an Individual.”

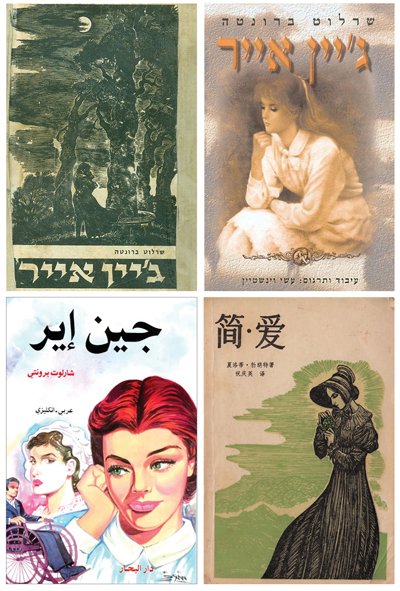

Based in Los Angeles and funded by PEN Center USA, the press publishes twelve books of translated poetry and fiction each year, and also produces literary films—video poems, paratextual films, and short documentaries—that feature the press’s authors and translators. A look at just two months’ worth of Phoneme titles is a trip across several continents: In December the press released Smooth-Talking Dog, a poetry collection by Mexican writer Roberto Castillo Udiarte—also known as “the Godfather of Tijuana’s counterculture”—translated from the Spanish by Anthony Seidman. Richard Ali A Mutu’s novel Mr. Fix-It, translated from the Lingala language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Bienvenu Sene Mongaba and Sara Sene, was also released in December. This month the press publishes its first Icelandic translation, Cold Moons by Magnús Sigursson, translated by Meg Matich; as well as The Conspiracy, a thriller by exiled Venezuelan novelist Israel Centeno, translated from the Spanish by Guillermo Parra. The Conspiracy is the second book in Phoneme’s City of Asylum series, which features works by exiled writers receiving sanctuary in the United States. Phoneme’s general submissions are open year-round, and can be sent via e-mail to

Based in Los Angeles and funded by PEN Center USA, the press publishes twelve books of translated poetry and fiction each year, and also produces literary films—video poems, paratextual films, and short documentaries—that feature the press’s authors and translators. A look at just two months’ worth of Phoneme titles is a trip across several continents: In December the press released Smooth-Talking Dog, a poetry collection by Mexican writer Roberto Castillo Udiarte—also known as “the Godfather of Tijuana’s counterculture”—translated from the Spanish by Anthony Seidman. Richard Ali A Mutu’s novel Mr. Fix-It, translated from the Lingala language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Bienvenu Sene Mongaba and Sara Sene, was also released in December. This month the press publishes its first Icelandic translation, Cold Moons by Magnús Sigursson, translated by Meg Matich; as well as The Conspiracy, a thriller by exiled Venezuelan novelist Israel Centeno, translated from the Spanish by Guillermo Parra. The Conspiracy is the second book in Phoneme’s City of Asylum series, which features works by exiled writers receiving sanctuary in the United States. Phoneme’s general submissions are open year-round, and can be sent via e-mail to

What’s different now that you’re coming on full-time as Guernica’s publisher?

What’s different now that you’re coming on full-time as Guernica’s publisher?

How has Amistad changed or grown in the past thirty years?

How has Amistad changed or grown in the past thirty years?