In February novelist Jonathan Lethem joined Bill Henderson, founder of the Pushcart Press, to launch a series of reissues of Lethem’s favorite forgotten books, starting with Bad Guy, a 1982 absurdist psychodrama by Rosalyn Drexler. W. W. Norton, Pushcart’s distributor, has signed on to distribute the new series under the imprimatur Lethem’s Legends.

Henderson and Lethem came up with the idea for Lethem’s Legends on the front porch of Henderson’s nine-by-twelve-foot bookstore in Sedgwick, Maine. Lethem, who summers in nearby Blue Hill, met Henderson at the local farmers market about fifteen years ago and occasionally visits what Henderson calls “the smallest bookstore in the world.” After hearing Lethem talk about his passion for rediscovering forgotten writers and books, Henderson proposed publishing a series of the author’s favorites. “It’s been my hope over many years to rescue books and rescue authors. That’s what we’ve done at Pushcart for almost fifty years,” Henderson says, referring to the annual Pushcart Prize anthology, which showcases the best writing published by small presses and journals during the previous year. Pushcart Press also occasionally publishes books that in-house editors loved but were rejected by their houses.

Lethem has long been a champion of titles that have fallen out of print. He points out that books by many of his favorite authors, from Philip K. Dick and Paula Fox to Melville, were at one time out of print. He adores the New York Review Books Classics series, which has republished hundreds of long-ignored gems and demonstrated that these books can still awaken the public imagination—and turn a profit. Lethem even coedited a title in the series, a 2012 book of selected stories by science fiction master Robert Sheckley. Still, the novelist sees plenty of room in the reprint market for “scruffy books that are even more lopsided and wonky or peculiar.”

Rosalyn Drexler’s Bad Guy fits that bill. The book revolves around a psychoanalyst who tries unconventional methods of curing her patient, a teenage rapist and murderer whose sociopathy has been fueled by television violence. Drexler boldly experiments with narrative and depicts sex and violence without apology or pussyfooting. “It’s emotionally sophisticated and savvy and street-smart,” Lethem says, “and in another way, it’s raw, antic, off-kilter, and unrefined.”

Drexler, who is ninety-two and lives in New York City, is best known as an early contributor to the pop art movement. She has won Obies for her playwriting and an Emmy for cowriting Lily, a 1973 Lily Tomlin TV special. She once toured the United States as a professional wrestler named “Rosa Carlo, the Mexican Spitfire,” and wrote about the adventure in her 1972 novel, To Smithereens. Bad Guy is the seventh of her nine novels.

Alhough Lethem’s wish list of potential reissues could easily fill Henderson’s tiny bookstore, the two are proceeding cautiously. If Bad Guy sells, readers can expect to see one or two of Lethem’s Legends released per year, beginning in 2020. “It’s going to be tough to bring back books in this current age when even new titles are getting obliterated by the cacophony,” Henderson says. “I call it the censorship of clutter. It’s hard for the average reader to find things that are truly valuable. That’s what we’re trying to do with Lethem’s Legends: bring back a few titles that deserve a second chance.”

Jonathan Vatner is a fiction writer in Yonkers, New York. His novel, Carnegie Hill, is forthcoming from Thomas Dunne Books in August.

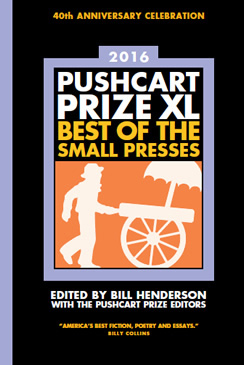

The idea for the Pushcart Prize anthology was first conceived in the early 1970s by founding editor Bill Henderson, who at the time was a senior editor at Doubleday. “I was tired of the publishing industry turning writers into dollar signs,” Henderson says, citing the tendency for big houses to favor marketability over substance. After leaving Doubleday, he self-published The Publish-It-Yourself Handbook: Literary Tradition and How-To, a guide that advised writers on how to start their own presses, free themselves from the constraints of commercial publishing, and express their own truths—a rally cry to rebuild the literary industry on the foundations of community and care rather than capitalism. (The handbook is now in its fourth edition, and has sold over seventy thousand copies.) To further champion the work of small presses and literary journals, Henderson began to conceive of a “Best of the Small Presses” prize and collected anthology—something that would highlight the poetry and prose being put out by indie publishers each year. He enlisted everyone in the literary scene that he could think of to help—Joyce Carol Oates, Ralph Ellison, H. L. Van Brunt, and Anaïs Nin, to name a few. They all got on board, and are listed as founding editors in this year’s anthology. Henderson used money from his book sales to get the anthology off the ground, and in 1976, from a shack in his back yard, he self-published the first annual Pushcart Prize: Best of the Small Presses.

The idea for the Pushcart Prize anthology was first conceived in the early 1970s by founding editor Bill Henderson, who at the time was a senior editor at Doubleday. “I was tired of the publishing industry turning writers into dollar signs,” Henderson says, citing the tendency for big houses to favor marketability over substance. After leaving Doubleday, he self-published The Publish-It-Yourself Handbook: Literary Tradition and How-To, a guide that advised writers on how to start their own presses, free themselves from the constraints of commercial publishing, and express their own truths—a rally cry to rebuild the literary industry on the foundations of community and care rather than capitalism. (The handbook is now in its fourth edition, and has sold over seventy thousand copies.) To further champion the work of small presses and literary journals, Henderson began to conceive of a “Best of the Small Presses” prize and collected anthology—something that would highlight the poetry and prose being put out by indie publishers each year. He enlisted everyone in the literary scene that he could think of to help—Joyce Carol Oates, Ralph Ellison, H. L. Van Brunt, and Anaïs Nin, to name a few. They all got on board, and are listed as founding editors in this year’s anthology. Henderson used money from his book sales to get the anthology off the ground, and in 1976, from a shack in his back yard, he self-published the first annual Pushcart Prize: Best of the Small Presses.