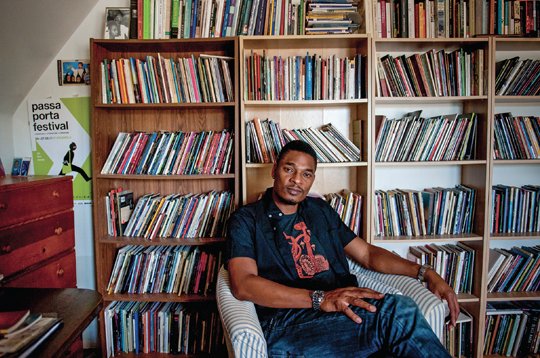

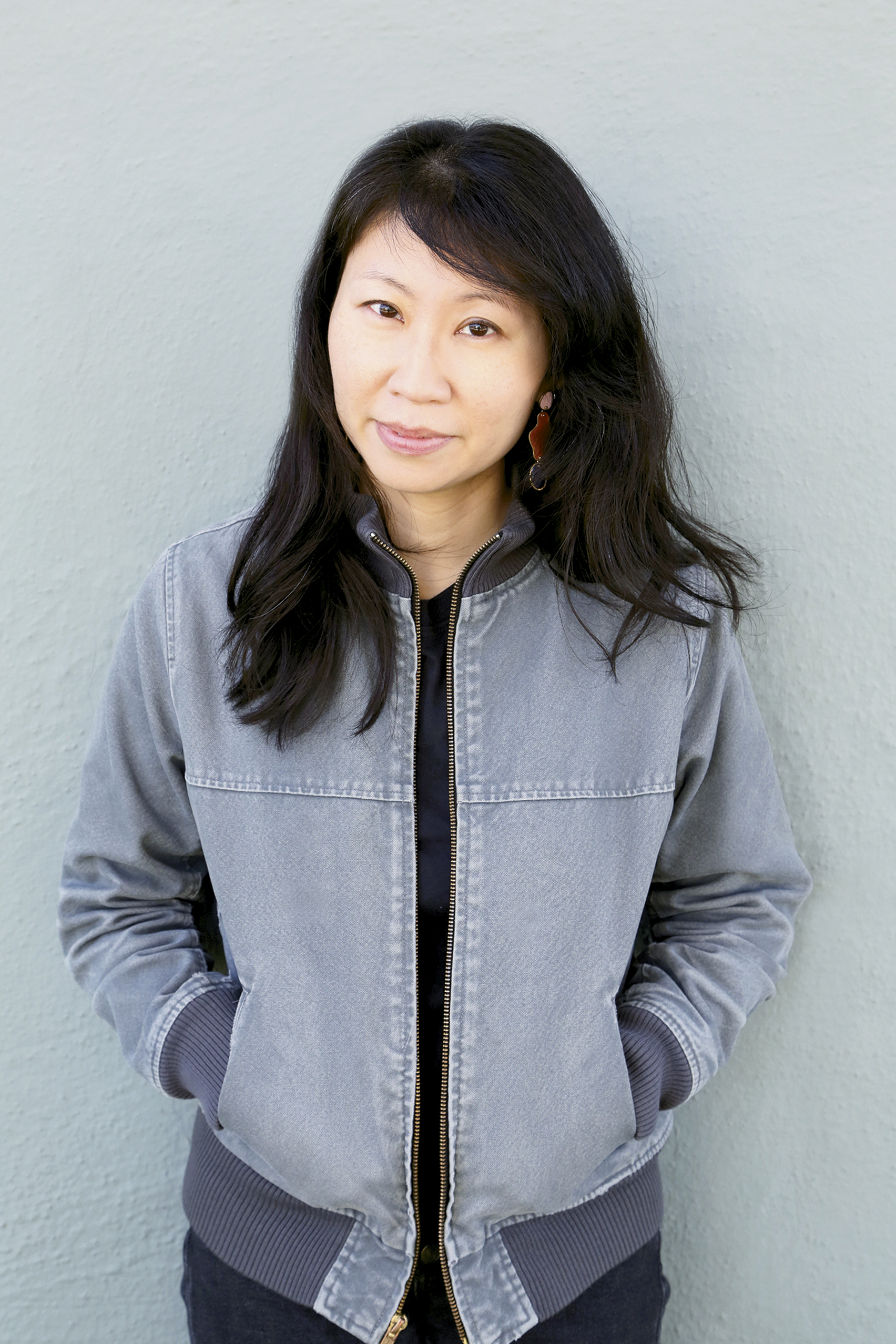

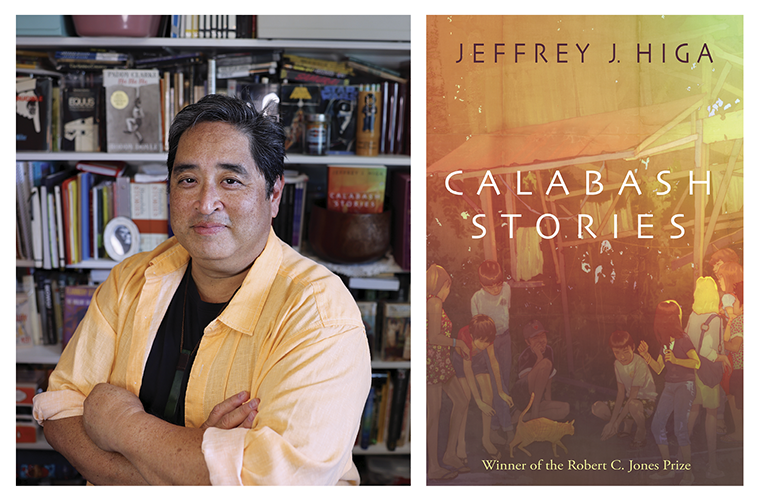

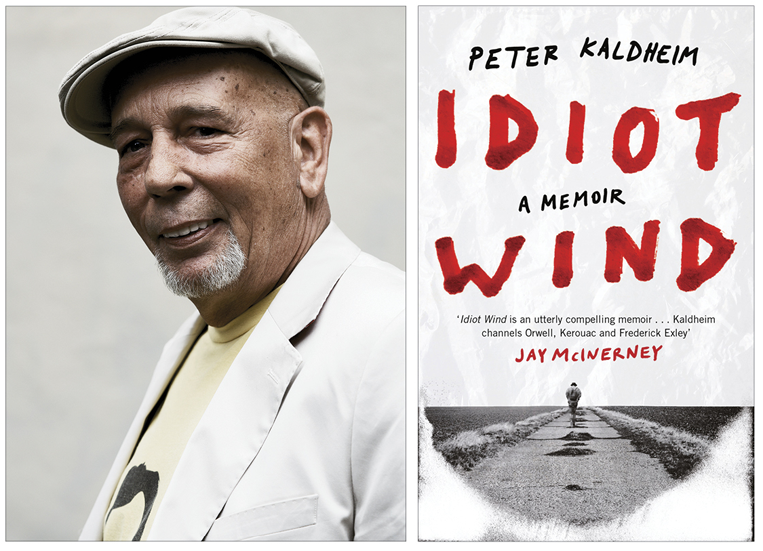

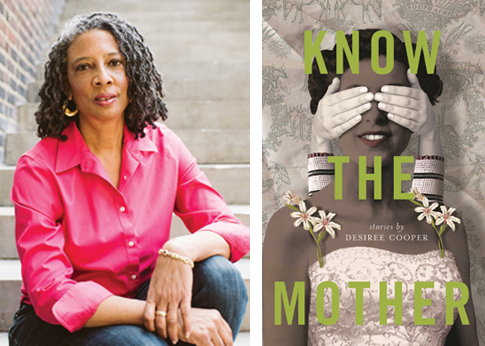

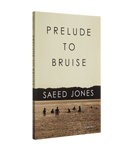

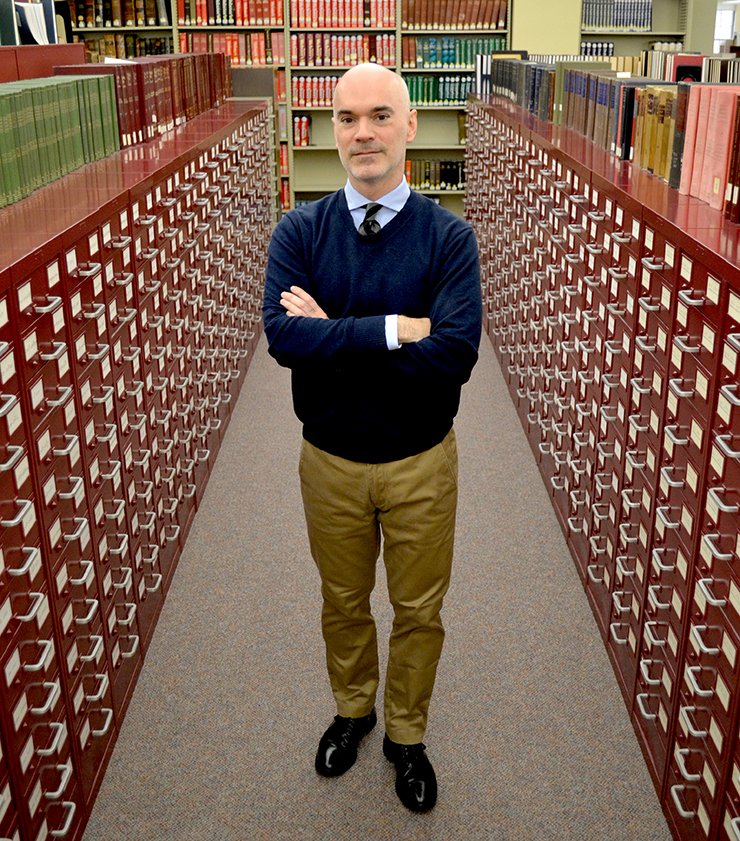

In West Mills

De’Shawn Charles Winslow

In October of ’41, Azalea Centre’s man told her that he was sick and tired of West Mills and of the love affair she was having with moonshine. Azalea—everyone called her Knot—reminded him that she was a grown woman.

“Stop tellin’ me how old you is,” Pratt said.

“Well, I thought maybe you forgot,” Knot retorted. She was sitting at her kitchen table, pulling bobby pins from her copper-red hair. She picked up her glass and finished what was left in it. She had barely set it back on the table when Pratt picked it up and threw it against the wall. He then packed all his clothes in the old suitcase he’d brought when he moved into her little house a few years back.

“I’m gettin’ outta here,” he affirmed.

“Need some help packin’?” Knot shot back, and she laughed. It wasn’t the first time Pratt had packed that ragged bag. He stared at her, frowning.

“Drink ya’self to death, if that’s what you want to do.”

“Go to hell, Pratt.”

“I’m leavin’ hell!” he yelled.

A few days later, Knot came home and found a folded note peeping out from under her door. First, she looked down at the signature. When she saw Pratt Shepherd at the bottom, she took a chilled glass from her icebox, poured a drink, and sat down to look over the message. She read most of it. It said that Pratt was at his sister’s house, just across the lane. Knot wasn’t surprised. Pratt’s sister and her two little girls were the only family he had in West Mills.

In the letter, Pratt reminded her that he still loved her, still wanted to marry her, and still wanted to start a family with her. He wrote that he would wait around for just one week. Then he was going back home to Tennessee. That’s where Knot stopped reading. She laughed out loud, tossed the paper onto the table, and set her glass down on it. Funny—it was usually the books she used to teach her pupils that got the wet glass.

Knot would be lying if she told anyone that Pratt wasn’t a good man. He didn’t mind hard work, he picked up after himself, he kept his body nice and clean, and he knew how to give her joy in bed. But the truth was Pratt wasn’t much fun to her otherwise. He didn’t have much to talk about. And he couldn’t hold his liquor to save his life. After two drinks Pratt was laid out, spilling over, or both. Knot liked men who could match her shot for shot, keep her mind busy when they weren’t drunk, and still do all the other things Pratt could do. Aside from all that, her father—she called him Pa—wouldn’t like Pratt. If she were ever going to be married, it would have to be a man her pa loved just as much as she did.

Pratt’s threat to leave West Mills could not have come with better timing, because Knot’s twenty-seventh birthday was a week around the corner. When the weekend came, she walked down the lane—two houses to the left of her house—to tell her good friend Otis Lee Loving all about her newfound freedom. And since Knot visited him most Saturday mornings, and knew he would be in the kitchen, she didn’t bother knocking.

“You need to go on over there and fix things up with Pratt,” Otis Lee said. “Otherwise, he gon’ be on the next thing headed west.” Otis Lee set a cup of black coffee on the table in front of Knot; his face was angry-looking and peach. He didn’t sit down. Just then, his wife, Pep, showed up at the table with a boiled egg and a biscuit, all inside the cracked, sand-colored bowl Knot wished they would throw away.

“Pratt can catch the next thing to hell,” Knot replied.

Pep pushed the bowl in front of Knot, next to the coffee.

She didn’t sit down, either. Knot looked up at them and wondered what the day’s lecture would be about.

“Eat,” Pep commanded. Even at seven o’clock in the morning, her round face looked full and healthy, as though she had slept on a pillow made of air. Not the rough, feather-stuffed pillows Knot used.

“I thought I left my mama in Ahoskie,” Knot scoffed. “Y’all got anything I can pour in this coffee? Something ’sides milk, I mean.”

“Why you so set on bein’ lonely, Knot?” Otis Lee asked.

Pep looked down at Otis Lee as though he had gone off script. And he looked up at Pep as if to say, I couldn’t help myself. The way he and Pep stood there, side by side, made them look more like a boy and his mother than a husband and his wife. Why the two of them behaved so much like old people, Knot never understood. They were only five years older than she was. For Knot, it was Otis Lee’s being happily married, being too short, and old-man ways that ruined the handsomeness she’d seen on him when they’d first met. And that handsomeness, as striking as it was, had never caused the feeling Knot got deep in her stomach when she met a man she wanted to touch, or be touched by, in the dim light of her oil lamp.

“Y’all know he tried to beat me, don’t ya?”

Otis Lee and Pep both sighed, at the same time. Knot wondered if they had rehearsed it.

“You sit to my table and tell that tale?” Otis Lee reproached. Then he began with his You know good’n well this and You know good’n well that. At times like these Knot had to work hard to keep her cool. Because if she didn’t, she might tell Otis Lee that if he spent more time worrying about his own life, and his own family, he might know that the woman he knew as his mother, wasn’t; she was kin but not his mother. If his real mama is anything like mine, better for him if he don’t know. Ain’t none of my business anyhow.

“Tell me one thing,” Knot said. “Why y’all always take his side?”

“It ain’t just about Pratt’s side, Knot,” Otis Lee insisted. “You need to be nicer to everybody ’round here.” Knot heard bits and pieces of what Otis Lee recounted about how her drinking had gotten out of hand; how she seemed to want to be by herself more than anything nowadays—unless she was at Miss Goldie’s Place, of course. Knot started nibbling on the biscuit and then on the egg, trying not to hear all the things she already knew about herself.

Otis Lee turned to Pep and mused, “You remember when she used to go see the children and they mamas, Pep? Used to visit people just ’cause she had time. People used to talk so nice about that, Knot. Thought the world of it. Didn’t they, Pep?”

“Yes, they did,” Pep replied.

Knot dropped the egg back in the bowl and asked, “Ain’t I sittin’ here, visitin’ with ya’ll right now?” Knot was certain they’d both heard her question, although neither of them responded.

“Now folk say you show up to that schoolhouse smellin’ like you bathe in corn liquor,” Otis Lee went on. “That’s ’bout all they sayin’ ’bout you now.”

“What people you talkin’ ’bout, anyhow, Otis Lee?” Knot said. She took a sip of the coffee. It was weak.

“What you mean, ‘what people’?”

“Y’all ain’t got but three or four hundred folk ’round here,” Knot pointed out. “And most of ’em is white folk who don’t know me from a can of bacon grease.”

“Some days you talk like you don’t live right here in this town,” Pep remarked. Knot couldn’t think of anything to say back.

She knew that some if not all of what Otis Lee was saying was true—about people whispering. Many times Knot had noticed how some of the women stopped talking when she came near them at the general store. And at the schoolhouse, she’d been a bit hurt by how some of the people had seemed as if they didn’t want to be seen speaking with her too long when they came to pick up their children. They’d ask how their little ones were doing with their lessons and then hurry off as though Knot had a sickness they didn’t want to catch.

Knot did her job. As much as she hated it, she did it well. No one had complained about her teaching. They couldn’t. So many of the ma’s and pa’s had themselves thanked Knot for the little rhymes and games she’d taught their children to help them divide a number quickly—without using paper and pencil. Or the funny ways she’d taught them odd facts. She remembered asking one of the boys one day, “Sammy Spence, what’s the capital of Iowa?” And once he’d answered correctly, she’d asked, “How you remember to keep the s’s silent?” and Sammy had responded, “My name got s’s, and they both make the s sound. But not for Des Moines, Miss Centre!” And Knot had said, “So you were listening, weren’t you?” And she had rubbed his head. When Knot had first arrived in West Mills, there were some eight-year-olds who couldn’t write their names. Her pa would have been just beside himself about that if she ever told him.

Otis Lee was still lecturing.

“You ain’t gettin’ no younger,” he cautioned. “Pratt love you to death, gal.”

“He left,” Knot said. “I ain’t throw him out.”

“This time,” Pep remarked, and she walked to the basin. “You got somethin’ to say, Penelope?” Knot shot back before realizing that her question would only bring on the second part of the Loving lecture.

Just three months earlier, Pep reminded Knot, she had thrown Pratt out for trying to do something nice.

“All he wanted you to do was stay home from that ol’ juke joint for one Friday night,” Pep recalled.

“But I felt like going,” Knot grumbled.

“He cooked a chicken for ya, child,” Pep said. “This one”—she pointed at Otis Lee—“can’t even boil eggs.”

“I can too boil eggs, Pep,” Otis Lee said. “You know good’n well I—”

“If I come home to a cooked hen,” Pep continued, “I’m gon’ sit with my man and eat.”

“He ask her to read to him, too,” Otis Lee informed his wife. “She tell him, ‘No.’ ”

Pep looked at Knot with shame.

Knot couldn’t deny any of it. It had been his request that she stay home and read to him that irritated her most.

“I read to folks all goddamn week long,” Knot had said to Pratt. “You crazy if you think I’m stayin’ home to read to yo’ big ass.”

“Selfish and stubborn,” he’d called her, shaking his head. And Knot had said, “I’m twenty-six years old. I can be selfish if I feel like it.” And Pratt had said, “Naw, you can’t, neither.” And Knot had yelled back, “Well, get the hell on out my house! Right now! And don’t you come back to my door.” He was back at her door, in her house, and in her bed in less than a day.

Otis Lee’s four-year-old son, Breezy, came scooting down the stairs on his butt. His little face was mashed flat on one side and his hair was full of white lint. He looked as though he’d been working in the cotton fields Miss Noni had told Knot all about. Breezy went and stood between his parents. Pep rubbed his head and pulled him against her thigh.

“Say good morning to Miss Knot,” Otis Lee nudged. And the boy did. Knot was glad Breezy was there to draw some of the attention away from her. She was done picking at the egg and biscuit, and done being picked on.

“You hear anything we just say to you, Knot?” Otis Lee asked.

Knot wiped her hands on the damp rag that was on the table.

“I thank y’all kindly for the breakfast. I’ll be goin’ on home now.”

“Go on over there and make things right with Pratt,” Otis Lee demanded. “You hear me?” He was looking at her as though she were a daughter or a sister he couldn’t control. Knot looked at Pep, and Pep turned and went to the icebox.

“The hell I am,” Knot said.

“Ma!” Breezy exclaimed. “Knot say a cussword!”

“I’m Miss Knot, lil boy,” Knot corrected. She couldn’t resist giving the boy a quick tickle on the neck. And she realized that she might be missing her nephews back in Ahoskie. “If yo’ ma and pa don’t let up, I’m gon’ let you hear some more cusswords.”

On her way out, she heard Breezy say, “Pop, Miss Knot got our bowl!”

Knot finished eating the egg and biscuit when she got back to her house, while she read a chapter of The Old Curiosity Shop. It was her pa’s favorite book, by his favorite author. And because he had read those big books to her with such joy, Dickens had become her favorite, too. Her pa had read that book to her more than twenty times when she was a small child. He used to sit on the floor next to her bed two or three times a week and read. Sometimes Knot saw specks of his patients’ teeth and blood on his shirts. It would make her mother angry.

“I ain’t got time to worry ’bout keepin’ shirts pretty, Dinah,” her pa would say to her mother. “Them folk be in pain when they come to see me. Half the time, they already tried to snatch the teeth out theyself.”

Knot’s pa shared with her his love for reading, no matter how tired he was. And each time, Knot would hold on to his long, rough goatee so that she would know when he got up. As hard as she would fight sleep, it won the battle every time.

On the night of her birthday, Knot spent close to an hour looking at the only five dresses she had liked enough to bring with her from Ahoskie. She modeled each of them for the little mirror on the wall. She had to stand far away from it to see her whole body. And when she walked close to it, most of what she saw was her pa’s V-shaped jaw. He couldn’t deny being my pa even if he wanted to. How many people in Ahoskie got a jawbone like Dr. G. W. Centre?

Knot ruled out the black dress and the white one. The pink one with the white bow, the green one with the blue trim, or the plain yellow one had to be the winner. Finally she chose the yellow one. She liked the way it looked next to her skin. Pratt used to tell her it made him think of peanut butter and bananas—something he loved to have on Sunday mornings. The dress was over ten years old, but that worked in Knot’s favor. It showed whatever curves she had, which Pep claimed were starting to go missing.

When the sun went down, Knot dressed up and bundled up. She walked the short distance—less than a quarter mile—to the dead end of Antioch Lane, to Miss Goldie’s barn house juke joint, where Knot knew people would be throwing away the money they should have been saving to buy their Christmas hams if they didn’t have a hog of their own. But with the Depression just behind them, and war hovering, ain’t nothing wrong with folk havin’ a drink or two in the company of other folk who want to have one or two.

Going alone to Miss Goldie’s Place reminded Knot of her first few weeks in West Mills, and on Antioch Lane, back in ’36. How nice it was to not have a nagging man looking over her shoulder, counting her drinks, or running off the friendly men she had met since moving there to take the teaching job her pa had arranged for her.

When Knot pulled open the big heavy oak door and stepped inside, the first thing she looked for was Pratt sitting at the piano, playing his tunes. He was nowhere in sight. What am I lookin’ to see if he here for? It’s my birthday. She would have stayed either way.

It wasn’t long before the friendly men started asking Knot unfriendly questions: You done put Pratt down again, Knot? And: Knot, is it true you plum’ put a piece of glass to Pratt’s neck? To some of the questions, Knot declared, “That’s a damn lie!” To other questions she replied, “That ain’t none of yo’ goddamn business.”

Knot left their tables and found company with the few men who didn’t know her name yet. And there was one, a young one, standing at the end of the counter. He was tall, just the way Knot liked them. He just might be the tallest man I ever stood close to. Pratt had held the record for the tallest and the stockiest. But this fellow was tall and slim.

Valley, Knot’s buddy who poured drinks at Miss Goldie’s Place, told Knot he was too busy to help her court. If she wanted to know who the young fellow was, she had better go and ask him herself, Valley said.

“And if he don’t seem interested in you, s—”

“Send him over to you?” Knot finished, knowing Valley’s taste in men.

“Yes, ma’am,” he whispered, and smiled.

“You ain’t gon’ be satisfied ’til you put yo’ mark on every man west of the canal,” Knot said. She and Valley laughed. Then he reminded her, first, that he hadn’t had any luck thus far and, second, that she’d promised to make him one of her famous Antioch Lane bread puddings before he was to leave to go out of town again. “Don’t start in with me about that damn puddin’, Val. If I do make it, I want my dollar—just like everybody else gives me for it.”

“I always pay you,” Valley said. “I don’t know what ya talkin’ ’bout.”

“You want me to go home and get my ledger?” Knot countered. Valley smiled and rolled his eyes.

Miss Goldie was sitting about midway along the bar, wearing overalls and a man’s shirt. She was smoking a pipe. Unlike most pipes Knot had seen the people of West Mills puffing on, Miss Goldie’s didn’t look as though it had been carved out of wood by a five-year-old. It was a nice pipe. Probably ordered it from Europe or somewhere.

Next to Miss Goldie was Milton Guppy, sitting there glaring at Knot as he always did. Knot never understood how he had gotten such a strange last name. The glares, however, weren’t a mystery to her. The teaching job her pa had set up for her had belonged to a Mrs. Guppy. And when Mrs. Guppy had been dismissed, she also dismissed herself from her marriage, taking her and her husband’s four-year-old son with her. No one knew where the two of them had gone, since she was rumored to have had no family to speak of. The mean looks Mr. Guppy gave Knot whenever she saw him—sometimes Knot thought he was even growling—were enough to let her know he hadn’t gotten over it. She sympathized. But it wasn’t my fault! I ain’t make her run off.

After a few months of Guppy’s glares, Knot had walked up to him once, up-bridge at the general store, and said, “If you got somethin’ to say, go ’head and say it and get it over with. I probably done heard it from other folk, anyway.” And Guppy had said, “I don’t b’lee I will, Miss Centre. Don’t want to make ya late for yo’ teachin’. Wouldn’t dare keep the good teacher ’way from the good teachin’ job she come here and steal.” And Knot had said, “I’m gon’ tell you the same thing I tell everybody else who got a problem with me being up at that schoolhouse.” And after she did, she’d told him, “Now you can go to hell.” She had left the general store without the hard candy she had planned to buy for the children.

Tonight, at Miss Goldie’s Place, Knot gave Guppy a Don’t look at me stare. She could tell by the evil look on his face that he must have already lost his week’s pay at the dice table.

Miss Goldie looked irritable, studying Knot and Valley. Finally, she cleared her throat in a loud This is for y’all to hear way. Knot knew Miss Goldie was watching every move in the building, and she didn’t like it when her workers carried on long conversation when they should have been refilling jars and glasses and collecting nickels and dimes.

Knot finished her first drink—it was her third, if she counted the two she’d had at home—and she danced over to that young man at the end of the bar.

“Tell me one thing,” Knot said to him. He was standing there in a suit. Lord, the man wore the whole suit to the juke joint. Whether it was navy blue or black, Knot couldn’t be sure. “You think yo’ people know you snuck out they house yet?”

“Well, if I had snuck out,” he replied, standing straight and putting his hands in his pockets, “they wouldn’t be able to find me. I’m a long way from home.” He didn’t sound anything like she would expect from a man of his height. He sounded as if nature had gotten tired and quit working halfway through his change of voice when he was a growing boy.

“I figured that part out already,” Knot said. And it wasn’t just the sharp suit that had given it away. His haircut can’t be more’n a day old. And he got the nerve to have a part shaved there on the side. Menfolk in West Mills don’t wear parts in they heads. Knot said, “I hear the North on ya’ tongue. Where’s home?”

“Wilmington,” he answered. “Wilmington, Delaware.

“I know where Wilmington is, thank you,” Knot retorted, and she wondered how she’d had all that schooling without learning there was more than one Wilmington—one other than in North Carolina.

She looked at him for as long as she could without feeling simpleminded. With teeth as straight and white as his, and with him not having a single razor bump on his chin, she was sure he wasn’t more than twenty years old.

“You can’t be more than nineteen, twenty,” Knot guessed aloud. He showed her a sly smile. I’ll be damned if he ain’t got dimples to go ’long with that grin. Shit, I don’t know if I ought to slap him or kiss him.

“People usually ask me what my name is by now,” he said.

Knot was about to tell him that she didn’t care what people usually wanted from him, but his eyebrows caught her attention. His eyebrows were so thick and neat against his smooth, black forehead, Knot wondered, If I stick the edge of a butter knife under the corner of one of ’em, would I be able to peel it off whole?

“Well, go ’head and tell me your name, then,” Knot said. He came closer to her, and she looked up at him.

“It’s William. And you guessed my age pretty close. I’m almost twen—”

“Buy me a drink, Delaware William. It’s my birthday.” Knot turned toward Valley and shouted, “Pour me what I like! This here fella’s gon’ give you the nickel.”

“William,” Delaware William corrected.

“Forgive me,” Knot said to him. And to Valley she said, “Delaware William’s gon’ give you the nickel.” When she looked back up at Delaware William, he was smiling again and shaking his head.

Valley came to the end of the bar where Knot was standing. With his finger, he signaled Knot to lean in. “Ain’t you got somewhere to be in the mornin’?”

“You ever hear tell of me not showing up?” Valley sucked his teeth. Knot said, “I didn’t think so. And I’ll thank you kindly to get me my drink. My damn birthday’ll be over, foolin’ with you.”

Valley fanned his bar rag at Knot. “You just as crazy as you can be, Knot Centre.”

“What was that he just called you?” Delaware William asked.

After Knot decided she wasn’t going answer him, she looked him up and down.

“My name’s Azalea.” And after he showed her a confused look, she said, “What’s ya business in West Mills, Delaware William?”

“I’m just William,” he said politely. “William Pe—” “What’s ya business here in West Mills, is what I asked,” Knot interrupted.

“We just stopped to rest. On our way back up from Georgia. Played some gigs down there for a few months.”

When she asked him to explain the we, he pointed to another young man who sat at a table with the pastor’s daughter. Knot was certain the girl had snuck out of the house. Without a doubt, it wouldn’t be long before the girl would give the young man what he wanted. Knot could tell by the way she was giggling. If the girl was anything like Knot was as a teenager, Knot knew how the night would end. And that young man would be leaving town soon after.

Knot, figuring she didn’t have more than a few hours with Delaware William, finished her drink in three swallows. Then she and Delaware William left, kissing and feeling on each other the whole walk back to her house. Between the heavy petting, she caught a few glimpses of the full moon. It was like an usher leading the way down an aisle.

“Looks like we’re in some damn slaves’ quarters or something,” Delaware William remarked. Knot couldn’t argue with him about that, even if she were sober. She had thought the same thing when she first moved to West Mills and rented the little house from a man named Pennington. According to Otis Lee and Miss Noni, Riley Pennington—Otis Lee’s boss—was a descendant of the line of Penningtons who had once owned the whole town, which, in those days, had been called Pennington, North Carolina. It didn’t change names until a man from Maine named Leland Edgars Sr. and his two sons—Miss Noni said they were both tall and handsome with long, pitch-black ponytails—moved to town with a bunch of Northern money. They bought up a bunch of land with trees and opened a mill on the west side of the canal, causing people to refer to the whole town as West Mills. And now, aside from the one large farm, the Penningtons owned only an acre here and an acre there.

“Used to be,” Knot said, and that was all she felt like telling him. “Now that you got ya history lesson, shut up and kiss me some more.”

When they arrived in front of her house, that same moonlight that had led them there showed her that Pratt Shepherd was sitting on her porch. He sat there as though he had been one of the first Penningtons.

“Young fella,” Pratt called out, “best if you turn around. Head on back up the lane so I can talk to Knot.”

Delaware William had his arm around Knot’s shoulder, and she felt it slide away. Knot leaned into him—she might have fallen over otherwise.

“Well, sir,” Delaware William said, “I didn’t hear her say she wants to talk to—”

“I used to know a boy that look something like you,” Pratt cut in. He stood to his feet. “Got his face cut up for walkin’ another man’s wife home. They cut that fella’s face up real bad. Right here on this lane.”

Knot didn’t get a chance to tell Delaware William that Pratt was no one to be afraid of; he had turned around and hightailed it back down the lane toward Miss Goldie’s Place. When Knot turned back around to face Pratt, he was sitting again.

“I’m gon’ count to ten . . . or eleven,” she slurred, steadying herself in front of the porch and placing her hands on her hips. “When I get through countin’, you best be off my damn porch or I’m gon’ have to hurt ya.”

“What? You got a gun, or somethin’?” Pratt taunted.

“Did you hear me say I got a gun?” Knot shot back. “I might, though.”

“Sit down, Knot. Sit on down here ’fore you fall and crack that lil head of your’n?” He patted the porch two times.

Knot spit on the ground and said, “My new man’ll come back and crack yo’ head open to the white meat.”

“Who?” Pratt asked. “The one that just run off? He ain’t even stay long enough for me to tighten my fist.”

Knot turned and looked down the lane. Delaware William may as well have been a ghost. Pratt, she discovered when she turned to him once more, looked as though he would die if he held his laugh in any longer. And once he let the laugh go—he slapped his knees, too—Knot said, “Go to hell, Pratt.”

She sat on the porch next to him and their shoulders touched.

“Happy Birthday, darlin’.” He leaned over and kissed her on the cheek. She swatted him away, but she was so glad he was there; something was stirring around inside her and she was in the mood for a man’s company.

Pratt pulled her close to him. She liked the way her ear felt against his fleshy chest. A whiff of his clean breath relaxed her. Pratt’s breath smelled as though he had chewed on mint leaves all day instead of just after dinner, as he usually did. Knot figured she would let him kiss her, knowing he’d happily join her inside the house, where he would make her feel good under the quilt. Hell, it’s my birthday.

In the doorway, Pratt kissed her face and neck. And before she knew it, they were on the bed they had been sharing, off and on, for two years. She didn’t know what it was, but it seemed as though his touch was different, better than before. “Feel like you grew some more hands,” she whispered in his ear before softly biting his earlobe. Did he put butter on his lips? She had never known his lips to feel as soft as they felt tonight. She enjoyed their new softness even more when Pratt kissed the insides of her thighs and moved up to her shiver spot.

Pratt laid his large body on top of hers. She imagined a giant pillow. As big—with just the right amount of heavy—as he was, that night he was a nice cloud hovering over her, making love to her. Knot knew she would certainly be hoarse in the morning.

Lord, have mercy.

When they were done, Knot lay there wishing Pratt would fall asleep so she could have one more drink. That jar is whistlin’ for me. But after all Pratt had just done for her, she didn’t want to spoil it.

The Dickens book was on the floor next to her headboard, so she decided to read for as long as her eyes would allow. But it sure would be nice to have a cool glass with a splash in it while I read. Damn! Pratt was wide-awake on the other side of the bed, picking with his toenails.

The next morning when Knot woke up, she lay there thinking about how she hadn’t gotten to do what she had wanted—in my own house. She nudged Pratt until he was awake.

“What is it?” he mumbled. He had one eye open, one eye shut.

“Get up!” Knot exclaimed.

“What for?”

“Get up and get the hell on outta my house.” And after he was dressed and about to walk out, she said, “And don’t darken my doorway. Never no mo’.”

“Azalea!”

“Gone!” she yelled, before slamming the door and making the drink she had wanted the night before.

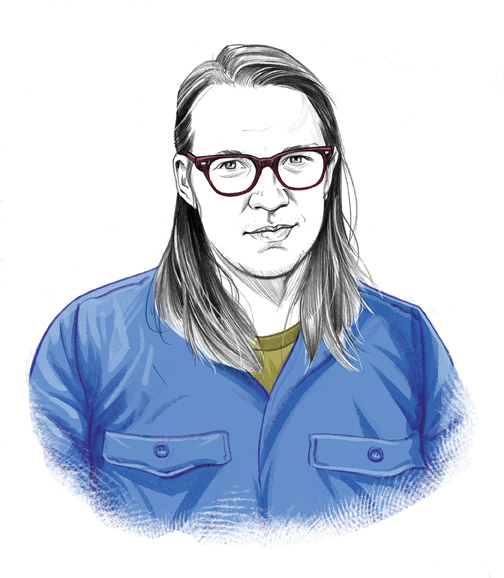

Excerpted from In West Mills by De’Shawn Charles Winslow. Copyright © 2019 by De’Shawn Charles Winslow.

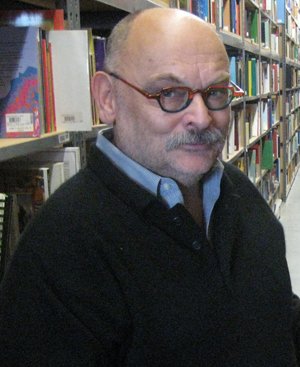

(Photo: Julie R. Keresztes)

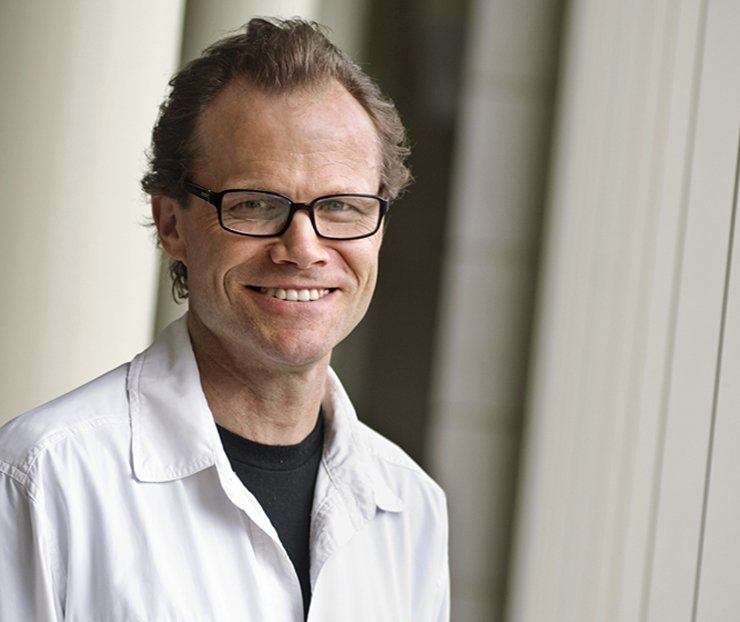

What were some of your best-selling

What were some of your best-selling

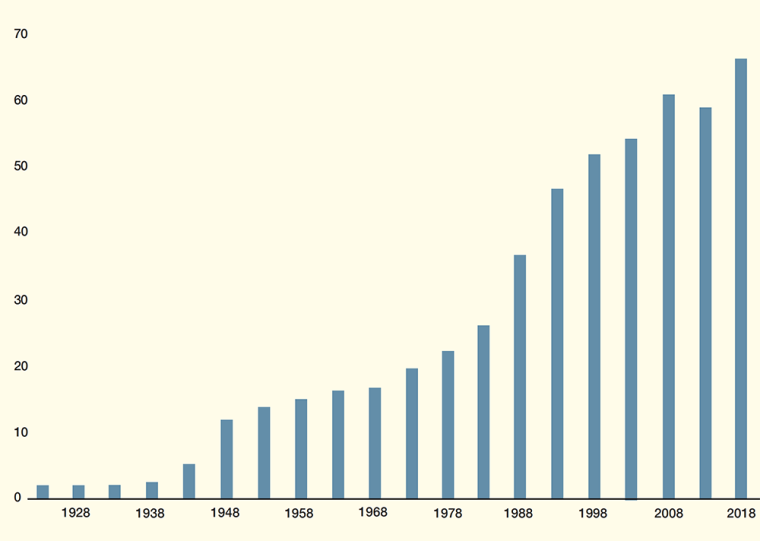

How has Amistad changed or grown in the past thirty years?

How has Amistad changed or grown in the past thirty years?