What’s the difference between writing a book and writing a screenplay? What are the different business models? If you’ve written a screenplay, how can you get it read? TD Donnelly talks about the challenges and rewards of screenwriting, as well as his first thriller novel.

In the intro, ProWritingAid spring sales 25% off; Key takeaways from the Future of Publishing conference [Written Word Media]; Curios for authors; Indie author’s scam survival guide [Productive Indie Author]; Writer Beware;

OpenAI’s 4o image generation model launch [OpenAI];

Plus, check out Death Valley: A Thriller by J.F. Penn.

This episode is sponsored by Publisher Rocket, which will help you get your book in front of more Amazon readers so you can spend less time marketing, and more time writing. I use Publisher Rocket for researching book titles, categories, and keywords — for new books and for updating my backlist. Check it out at www.PublisherRocket.com

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

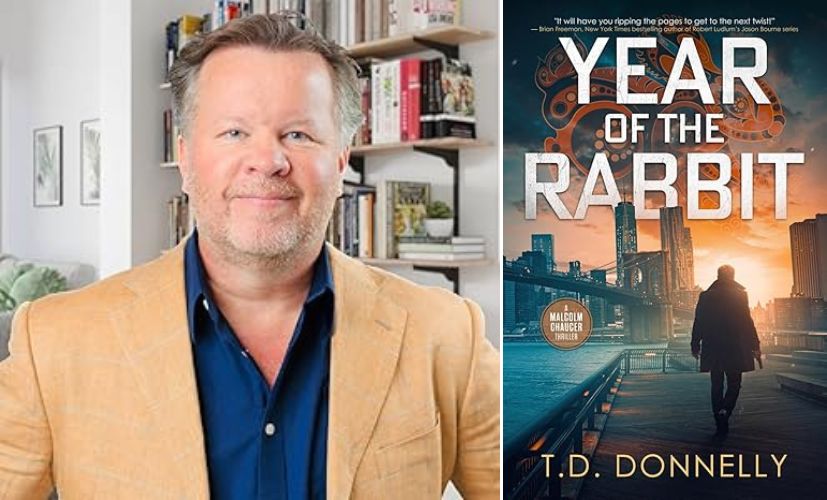

T.D. Donnelly is the author of the thriller The Year of the Rabbit. He’s also been a screenwriter for more than 25 years, with credits including Sahara with Matthew McConaughey, Conan the Barbarian, and adaptations for the works of Ray Bradbury, Clive Cussler, Stan Lee and others.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Challenges of being a screenwriter

- The competitive nature of the film industry compared to indie publishing

- Payment structure for screenwriters — stages of payment, production bonuses, and residuals

- Regaining rights to old, unpublished screenplays

- Writing differences between screenplays and novels

- Craft and pitching advice for aspiring screenwriters

- Why Tom is not worried about AI in the film industry

You can find Tom at TDDonnelly.com.

Transcript of Interview with Tom Donnelly

Joanna: TD Donnelly is the author of the thriller The Year of the Rabbit. He’s also been a screenwriter for more than 25 years, with credits including Sahara with Matthew McConaughey, Conan the Barbarian, and adaptations for the works of Ray Bradbury, Clive Cussler, Stan Lee and others. So welcome to the show, Tom.

Tom: Hey, Jo. How are you today?

Joanna: Oh, I’m good. It’s really fun to talk to you about this. So first up—

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into screenwriting and, particularly, into adaptations.

Tom: Okay, so I grew up in New Jersey. My father was an accountant in Manhattan, and my mother was a housewife raising three boys, which is not easy, and sometimes doing a little bit of real estate. So nobody in my family had ever been in a creative field.

I had no connection, but what I did have was a 20 minute bike ride from my house growing up, sometime around 10 years old, they built a multiplex, like a 10-movie theater. Back in the 80s, that was quite something.

I figured out that on a Saturday, I could ride my bike down like four blind alleys and along the median of a six lane highway for a little bit. It was probably not a good idea, but I could ride my bike to that movie theater, chain it up, spend three or four bucks for a matinee ticket, and then sneak into at least two other movies after that.

I was absolutely hooked. I was like, oh my god, this is the best. This is the 80s. This is Raiders of the Lost Ark and Empire Strikes Back. I was transported every weekend into other fantastical worlds. I feel like it indoctrinated me into story and into the scope of story and the power of story.

It was all the idea that the Japanese, they have a 100-year plan. When you want to become something in Japan, you apprentice for 10 years, and you just spend all those 10 years learning everything you can so you can become an expert. I guess we call it the 10,000 hours now.

I realized at age 15 hearing this, I had like a brainstorm. It was like, hey, if I did that, that’s about 10 years of my life. I would still only be like 25 or 26 if I spent all my time just trying to be a screenwriter.

If I did that, I would be 25, and if it doesn’t work out, I could still do something else at that point. I’m still really young and all that sort of stuff. So I kind of set out with that goal in mind.

I told my guidance counselor in high school, I was like, “I would like to be a screenwriter in Hollywood.” The guy just looked at me like, where do you think you are? What planet do you think you are on? Just had no idea what to do with me.

He kept trying to suggest other careers that were reasonable, and I just was adamant. So he was like, okay, I’m just going to wash my hands of you and let you go. I’ve never reached back to contact him, but that would have been funny.

Anyway, I got my undergrad at Vassar with an English and Drama double major. Then I got accepted to USC Film School for a master’s degree in the directing program, actually.

My thesis script—this never happens, okay, I want to preface that this never ever happens—was the first feature length script that I ever wrote, and it ended up, two or three years later, being sold in a bidding war.

I ended up getting hip-pocketed. Hip-pocketing means that an agent says, I’m not going to put you on my official roles, and we’re not going to go through the official channels and stuff like that, but I will help you. I will read your stuff, and I will give you notes. If something happens, then we’ll talk about me representing you officially.

Anyway, I had an agent that was hip-pocketing me, and at the time I was editing to pay the bills. I was editing film and television, in particular television at that point. The producer I was working for wanted to hire me immediately onto another television project.

I said, “I’m sorry, I can’t do that.”

He was like, “What? I thought I thought we had a good relationship.”

I said, “No, we have a great relationship, but I’ve saved up enough money to write for six months, and whenever I’ve saved up enough money to write for six months, I always don’t take an editing job because I don’t want to just be an editor. I want to be a filmmaker. I want to be a writer.”

He was like, “Oh. Oh, do you have anything to show me?”

I said, “Well, I have my thesis script that I wrote in college.”

He was like, “Can I check it out?” And he read it, and he said, “I’d like to send it to a couple of my friends. Would that be all right?”

I said, “Sure.” So I called the agent that was hip-pocketing me, and I said, “Hey, great news, this producer, this guy, he wanted to share the script.”

My agent was like, “What? He can’t do that. When he does that, he’s attaching himself as a producer.” I’m like, oh no. So he’s like, “Who did he give it to?”

I said, “I don’t know.” So long story short, too late already. So sorry, so sorry.

He finds out the three people that this producer sent them to, and it ends up it’s the head of 20th Century Fox Production, the head of another—like three very big people—and calls up the first one and says, “There’s a script that came to you last weekend. It should not have gone out. I just want to claw it back until it’s ready.”

They’re like, “Oh, we were just about to call you. We’d like to put in a bid on it.”

After that, everything changed. Suddenly, we’re in a bidding war. There ended up being three different bidders, and the script sold for—well, let’s just say this. At the time, I had over $100,000 in student debt from grad school and undergrad, and with that sale, I paid off every single debt that I had. I was free and clear. It was amazing.

Joanna: So first of all, you seem very mature as a child to decide that you want to—or as a teenager—to sort of decide, yes, I’m going be a screenwriter. Then obviously you making the choice to study it, and then everything falls into place.

I guess by the time you did that major deal in, I guess it would have been the, what, late 90s by then?

Tom: No, early 90s. Yes, early 90s.

Joanna: Early 90s, okay.

Tom: No, ’95. Sorry.

Joanna: ’95, and you’ve stuck at this career since then.

This seems incredibly single-minded to me.

Tom: It’s weird, but I basically came at it from this viewpoint. I love storytelling. I love stories. I love movies. I love books. My mother would, when I was a kid, she would drop us off at the public library, sometimes all afternoon as she would go out and be doing real estate things. So we read everything in the library. We were indoctrinated in story from a very early age.

I said, if I’m this fortunate to be able to try and fail things, I better do that because I don’t want to have regrets. I don’t want to have regrets in my life. I don’t know why I realized that at such a young age, I don’t understand. If you ask my wife, I’m not a wise person. I’m really not.

Joanna: Maybe you’re just single-minded.

Tom: A little bit. I said, if I could do this as a career, I think I would be happy for my whole life. That thought, once that got in my head, it kind of never left, and it has absolutely been true.

As difficult as the writing life can be, it is such a joy each day to know that I’m making something that’s never been and I’m putting into the world. There are people that are reading the stories or watching the movies that I’ve been a part of.

For some of them, it’s exactly what they needed at a low moment in their lives. Or for some it’s like it spoke to them in a really deep and human way. I just think that’s magic, and if I could be a part of that, I love it.

Joanna: Well, then you mentioned were difficult there. This is really interesting because, of course, I’ve talked to screenwriters over the years and sort of dipped my toe in and backed off.

People hear negative things in the author book industry as well, but what are the difficult things about being a screenwriter? I mean, as in, has just everything been amazing, and like you said, you’ve been happy for your whole life?

What are some of the challenges of being a screenwriter?

Tom: Okay, so one thing, I’ll phrase it this way, Craig Martelle in 20Books, they say, “A rising tide raises all ships.” In that my success does nothing to harm you. If anything, it might even help you. If I’m putting out a good book that’s in a genre that you’re in, it’s going to make people want to read more, and probably read your stuff as well.

In the film business, in the television business, that is not the case. It is a knife fight in a phone booth. It really is.

So let me give you a number here, 50,000 screenplays. That is the number of screenplays that are registered with the Writers Guild of America, of which I am a member, every single year. Of those, there’s 20 times as many that are written every year.

So that is a million scripts a year, and that’s just in the US. That’s just scripts that are in the North America market. A million scripts every year. Do you want to know how many films were made in North America in 2023?

Joanna: Go on, then.

Tom: 500. So taking the, “a rising tide raises all ships,” if you end up getting one of those 500 slots to make a film, that absolutely affects me and everybody else. It is not a “we’re all in this together,” it is very much cutthroat. The industry is built that way.

A lot of times when there is an assignment, people don’t just come to me with a book and say, “Hey, would you like to adapt this?” More often than not, they’re going to four or five writers that are just as experienced, just as talented, just as right for the material as I am.

I have to go in, and I have to pitch, and I have to somehow convince these producers and these multi-billion dollar conglomerates, international conglomerates, that I have that special spark that is going to get this project over the line and is going to make this something that is going to make them a ton of money.

That’s not easy. That is super hard. In some ways, selling my very first script I ever wrote was an impediment to that because I suddenly was thrust into the lunch meetings, and the getting to know yous, and all that sort of stuff. I was thrown into the deep end before I really had figured out a lot of this sort of stuff.

So I had on the job training, as opposed to make all your mistakes in private, in the dark when nobody can see you. I had to learn a lot of these things the hard way, and it was really, really difficult.

Joanna: I guess of those 500, as you say, I mean, a lot of those are from existing screenwriters, like yourself these days, and also existing franchises. So of that, let’s say—

Of those 500, how many are like original screenplays that people pitch?

Tom: Not many. Not many at all. I can’t really give you a number, but I would probably say only 10 – 20% are completely original material. The reason being, the film business in particular, is the last truly gate kept industry.

Back in the 70s and 80s, the music industry was a gate kept industry. If you wanted to put out a record, you had to have a record deal with a major label.

They would have the fancy studios, and the backup artists, and everything you needed to succeed, but they would take the majority of the profits. You would still make a fortune, so you wouldn’t be too unhappy about it.

Then when digital recording equipment came out, all of a sudden, everybody could do it. They could record in their garage something that was good enough and good enough to get on air. Suddenly, within 10 years, the record industry collapsed.

The same thing with Kindle for us. The stranglehold that the big publishing houses has had over the industry collapsed.

For film, it’s a collaborative, very difficult experience. It takes a lot of people to make a film. It takes a lot of equipment. It takes a lot of time. So the lowest entry price you can make a film for is still very expensive.

Listen, I’ve worked with Robert Rodriguez, who made El Mariachi for $7000, $8,000. Amazing guy. I love him to death. It’s not easy to do that. It’s super hard to be the exception that can make things at that low of a budget level and really do it indie. It can still be done.

There are more and more opportunities do the to do that now, but because everything is so expensive that affects what people buy as well. People want assurances in this industry.

They don’t want to buy a spec script. No matter how good that spec script is, they know that spec script has only been read by 10 people, 15 people.

They would much rather have a book series that they know have sold a million copies worldwide because that has pre-awareness.

That has a promise of, hey, a large part of those people are going to want to come and watch this movie. So we can afford to spend the $50 million, the $60 million, the $200 million on that project, to get it up and going. That’s just the reality of the business.

Joanna: Although we should say, so you are a screenwriter in LA. You’re obviously in the US Hollywood film industry. There is obviously the indie film market. There’s film industries here in Europe, there’s film industries in India. There’s film industries all over the world. So, just for people listening—

You have a particular perspective based on these very big budget films, right?

Tom: Yes, I absolutely should say that. Not only do I write in Hollywood, I also write on the very high end of Hollywood productions. I did a lot of work on Marvel’s Doctor Strange and Cowboys and Aliens and like these big, big, big, big, $200 million pictures.

I know what the budgets are for BBC productions. I know what the budgets are for ITV, for Canal+ in France. I know what they are. They’re lower. There’s more opportunities in some of those places.

There is a kind of universal understanding that for most projects that end up getting made and end up getting distributed, the price to get into that, the minimum cost for most of these films is still, even if it’s not $100 million, $200 million—hey, guess what? $5 million is a lot of money.

That is still a barrier to entry for a lot of people, and it’s a barrier to raise that amount of money in the hopes that that is going to make that money back for a lot of people.

Joanna: You know, I was at the Berlin Film Market, and I learned a lot about all of this, and a lot of the networking is about finding all the different ways you can fund things. So you get a little bit from here, a little bit from there, you get a bit over there, and a grant from that location. It’s just incredible to me how this works.

Let’s talk about the business and the money side. We’re going to come back to your thriller writing books in a minute. In terms of the business and the way the money works as being a screenwriter compared to owning and controlling your own intellectual property. So can you give us a bit of an idea about that?

Are you essentially a very highly paid freelance writer?

Tom: Yes, that is exactly right. All work in Hollywood is work for hire, meaning when I sell a script, they buy the script outright. They own it, they own the rights to it. They can do what they want with it. I have certain—because I’m in the Writers Guild of America—I have certain rights that are reserved to me.

So if they want to make a sequel without me, they still have to pay me for it. I still get credit on the project, etc, etc, but they do own the things outright. Maybe my deal has licensing money for toys or all of this sort of stuff, but usually not.

Generally, I get paid in stages. I get paid a certain amount for the first draft, a certain amount for the rewrite, a certain amount for any polishes that I do after that. When the movie goes into production, I get a production bonus in the first day of shooting.

When it’s completed and the credits have been established and negotiated and dealt with, I get a credit bonus. Then you start to get residuals after that. My wife calls them the green envelopes of joy.

Four times a year, the green envelopes of joy appear on my doorstep, and you never know what they’re going to be. You have no idea until you open it. Now you have some idea because it’s a big film that came out, and there’s a good chance that that first envelope is going to be huge.

It tails off fairly slowly, actually, but over time, it tails off. Eventually you start getting green envelopes of joy that are for $2.50.

Joanna: It might have been a coffee once in LA. It probably isn’t anymore.

Tom: Exactly. It feels a little like Patreon. It feels like the studios are now just contributing to my Patreon.

So which is to say that you don’t own it, which is a painful reality. Now, though you don’t own it, the amount that they pay you to write it is embarrassingly big. The industry compensates writers, or at least writers at my particular area, very well. It is a well-compensated business.

A famous author who came to Hollywood and started writing for Hollywood couldn’t believe what they paid until he saw how he was treated, and he said, “Oh, they’re not paying me for the writing, they’re paying me for the indignity,” which I continue to believe is true to this day.

The writers are not treated the best in my side of the business. I will say that when I hired an editor from Bath, England, who was editing my first novel, she was apologizing and giving me all these caveats as she was giving me the sweetest, nicest notes I’ve ever received in my life.

She was thinking I was going to be offended by her suggestion of changes. I’m like, oh my god, you have no idea what notes in Hollywood are like. Oh my god. It’s just so awful in comparison to this.

Everybody on the indie publishing side of the business, you guys are so sweet and so nice. I feel like I’ve left the real world and I’ve entered, I don’t know, the world of the Smurfs or something. Everyone’s super nice to each other. It’s amazing.

Joanna: That is so funny. Well, then let’s come back to—

Why the hell write a novel?

If it’s all so wonderful and unicorns and roses in Hollywood—maybe they treat you badly or whatever, but they pay you well—why write The Year of the Rabbit? Which I should tell people I’ve read. It’s very, very good. So obviously you can write, you can tell a story, but why bother when you’re just doing all this amazing work?

Tom: Well, okay, so here’s one little fact. Hollywood buys between 10 and 20 projects for every one that gets made.

So that means, over the course of my career, they have bought so many projects that I have spent six months to a year writing, and rewriting and rewriting again, and honing to the best of my ability to compete in that knife fight in the phone booth that I’m talking about, and to make it like, just sing, just perfect.

Then it still does not get made, and that project ended up being seen by 15 people in the world. 15 people ever know that that thing existed, and it’s gone. It’s just out there.

Well, guess what? I’ve been writing for almost 30 years now. Those rights have reverted. Those projects, there’s nothing saying that I can’t take those projects and give them a second audience, give them a second chance at life.

Even other ones where it’s my work on that project didn’t end up get getting used in the final project, but god, I love the idea that I had for that. So what could I do? I decided that now, you know, I’m in my 50s. Congratulations, 50, Jo.

Joanna: Thank you. What a wonderful decade.

Tom: It really is. I’m loving it so far. I am absolutely loving it. It’s a time when, for me, I was like, okay, let me look at the latter half of my life, and is there anything I want to do different?

I decided that I wanted to take some of those stories that I was well compensated for writing, but never got a chance to be in front of an audience. I could put these in front of an audience now.

I can have a second bite of that apple, and I can explore this space where I have total creative control, as opposed to almost no creative control over a project. I thought that was fascinating.

Joanna: So just on that, this is the 30-year copyright for scripts?

Tom: It’s actually less than that within the industry. I wish I had the number in front of me. Within the Writers Guild, there’s a negotiated point at which you can regain the rights to a project.

Sometimes you have to pay what they paid you, but in a lot of cases, you can literally call them up, talk to them, and say, “Hey, I kind of want to do something with this. Do you guys mind at all?”

A lot of times, they’ll just say, “We haven’t thought about that in 15 years. No, go ahead. Do whatever you want.”

Joanna: Take it away.

Tom: Exactly.

Joanna: Okay, so that’s cool. Okay, so then how did you find the process?

What is the challenge of writing a novel to writing a screenplay?

If people haven’t read a screenplay, just explain the difference.

Tom: Sure, sure, sure. Well, how should I put this? What you guys do as novelists—and I’m saying you guys, even though I’m a novelist now, I’m still a little bit on the outside looking in—it’s cheating. It’s not right. It shouldn’t be allowed.

I’m very, very mad that you guys get to write the way you get to write, and I’m stuck in screenplay format having to do it the hard way. You guys get to write the characters’ interior thoughts and emotions and journeys, and that is cheating and it is wrong.

I have been trained since I was a young person that, no, you can’t do that. You have to imply a character’s emotional state through very carefully crafted dialog and situation and moments. The entire structure of a scene is designed to elucidate a character’s internal state that cannot be understood any other way.

That’s screenwriting. That’s what that is. I mean, that’s why we’re so good at dialog. We’re so good at dialog because we can’t tell you what a character is thinking. Yes, people could do voiceover sometimes, but that is a pitfall of its own accord, unless it’s done very, very well. So you have to be careful about that.

So you’re stuck to two senses in screenwriting, what you see and what you hear. That’s it. No thoughts.

There are heavy structural demands. A screenplay has to have a—there could be a 3-act structure, 5-act structure. You can make a lot of arguments for how it needs to be structured.

Tons of times I’m reading a novel, you know, I get sent several a week from my agents who say, “Hey, check this out. People want to consider you for this.” Lots of novels, their structure is such that it would need a lot of heavy lifting to become a film.

Even Sahara, for instance. In Sahara, the bad guy, all the villains die, and there’s still 100 pages left in the novel after that point, 80 pages left at the end of that. You can’t really do that in a film.

I mean, Peter Jackson, God bless him, tried to do the ending of Return of the King, the Lord of the Rings trilogy. There’s still jokes flying around the internet about how many endings that thing has. It just keeps going on and on and on.

I think he did a great job and won the Academy Award, so kudos to him. In general, you can’t do that. So structure is something that is very, very important.

Pacing demands, right? Film travels at 24 frames a second through that projector onto the screen, and it does not stop, it does not pause. It does not allow you to go out and get a coffee.

I guess now with streaming, you can pause anytime you want, but it is still designed for you to watch in one go to be sitting there and experiencing that.

Then there’s the length issue. Sahara was a 193,000-word novel. The screenplay for Sahara was 23,000 words.

How do you take a 193,000-word experience and create a similar story experience in just 23,000 words?

In order to do that, no scene is about one thing. In a novel, scenes are about one thing all the time. In a screenplay, every scene is about four or five or six different things stacked on top of one another, very artfully folded in on each other.

So we’re advancing this plot element here. We’re advancing this character conflict here. We’re hinting. We’re doing setups and payoffs for this and that and the other thing that are going to come 15, 20, 45 pages later. All of these things are happening in one scene, and that creates a need to rewrite a lot more than novelists sometimes do.

Some novelists rewrite and rewrite and rewrite, I get that, but for the most part. It makes it hard for discovery writers, frankly. There are not many discovery writers in Hollywood. It’s a very difficult thing.

First of all, because you’re constantly having to share your work with the producers. So you’re sharing outlines and pages and all of that sort of stuff. Just saying, “I’m not really sure what the story is going to be about. I have some ideas, but let me just see where it goes.”

Joanna: I’m just going to make it up.

Tom: You don’t get a very good response for discovery writing. Now that said, there are some. Like Greta Gerwig famously said that she has to start writing to understand what her story is, and I love that. I love that there are, even in Hollywood, there are discovery writers.

Her and Noah Baumbach, when they wrote Barbie, did a lot of discovery writing. I think it shows in the work that the depth of the theme of that movie is so evident, and I feel like it doesn’t come from an outline. I think that comes from discovery writing, to some degree.

Joanna: I mean, as we record this, even just this morning, I’ve been editing my Death Valley script again. I guess in terms of editing as a discovery writer with the novel, it’s a different process, but it is actually much easier to edit 110 pages, 120 pages, or whatever, of quite spaced out—because of the way screenplays are formatted.

It’s much easier to edit a script than it is to edit a whole book.

Tom: I mean, it kind of is, but maybe you’ll find in some ways, it also isn’t. In a screenplay, because things are so dense and so layered, you have a lot more of the “pulling on a thread and the entire sweater falls apart.”

That can happen a lot more in a screenplay sometimes, whereas the spaced out editing of a novel gives you more on ramps and off ramps to get out of the story problems you’re creating for yourself in the rewriting process. Maybe. At least that’s what I’m finding.

So, yes, I am finding editing my novel is very difficult, and I’m very happy to have somebody doing it with me and kind of for me. I’m in that process right now on the second novel, and every time I go in to fix something, I end up adding new chapters.

I’m like, oh god, what am I doing? Am I ruining this? All my film instincts are yelling at me, “Don’t! What are you doing?”

Joanna: I think that’s interesting because readers of books, of novels, are a lot more forgiving. When you think about the target market for a screenplay, it is a very small group of very, very picky people.

Whereas the target audience for a novel is a lot wider, and they’re not necessarily people who are picky about—or they are picky in some ways—but they’re not the same. So it feels like the target audience is so different, even though, obviously, eventually you hope your film will be shown in front of people.

Most people will never see your script, right? It’s a very small audience.

Tom: It’s so true. The way I describe it is, when you submit a screenplay, you’re giving it to readers who are paid to say no. When you write a novel, you’re giving it to readers who have already paid to say yes. That’s a radically different experience.

Joanna: And they paid lot less, by the way. Or nothing in Kindle Unlimited.

Tom: It’s unreal. Exactly, exactly. That is a major, major difference. In screenwriting, you are writing to a hostile audience, like an incredibly hostile audience, that is all trying to figure out how not to lose their jobs if this thing gets made and fails. That is the sad truth of the matter.

Joanna: So you mentioned there about submit your screenplay, and this is obviously one of those interesting things. For me, and maybe other people listening—

We’ve maybe written an adaptation of a novel, or we’ve written a spec screenplay, and where do we submit it?

Now, I’ve obviously been to some pitch things. I am now looking at some competitions. So what are your thoughts on our scripts, if we do write them and obviously try and make them the best they can be first, but where should they then go?

Tom: Okay, so you’re getting really into hard questions now. I was told this would not be an ambush interview. This is not fair.

Joanna: It’s so not.

Tom: Let me ask you a question, Jo. You asked me for some advice when you were about to go to Berlin, to the film festival and to the film market. Did you take my advice?

Joanna: Well, you said, don’t even write a script.

Tom: I was very specific about how you had to pitch yourself, and you were like, “Oh, but we’re British. We don’t do that. This is Europe, we don’t do that.”

I said, “No, they still do it in Europe, just maybe not quite as brashly as the Americans do.”

Joanna: No, I didn’t. I don’t think I’m very good at that. I am feeling a lot better about that. Now I know a lot more about the industry. I think I needed to be there to kind of understand. As you said, what was so funny was how much, not contempt, but they don’t think much of writers, as you said. It’s crazy to me.

Tom: No, I mean, from an indie writer’s point of view, it’s shocking, because all you do is run into people that are, “Oh my god, I love your podcast. I love your book. I love your this. I love your that.”

They’re like, “Oh geez, another writer. All right, fine. You’ve got three minutes. Tellme what you want to say.”

Joanna: So what can we do?

Tom: There is no way to break into Hollywood, and yet it happens every day. There is no way to get a film made in Europe, and yet it happens every day. The sad fact of the matter is, as I already mentioned, because of the cost of making these things, it is very difficult to get scripts read and seen and accepted.

Every step of the process is a struggle because of the time and effort and cost involved in the endeavor in and of itself. So, that said, there are things you can do to increase your chances of having success here.

If you ask me before you write anything, what can you do to up your chances? I will say, if you can write a high concept, low budget, contained-space story with powerful characters and theme, you are going to leapfrog over 90% of all other scripts that have ever been written and put yourself into contention.

Those are projects that are eminently producible. When I say contained, I mean one or two locations. I mean really, really contained, simple ideas.

I was on the screenwriting panel at 20Books Vegas two years ago, at the last 20Books Vegas, and a romance writer said, “Yeah, well, that’s all great and good, but I’m a romance writer. You can’t write a contained romance.”

I said, “Sure you can,” and I was like, “What about this? Two people—a man or woman, or depends, man and a man, whatever your genre is, whatever your tropes are—are invited to a ski weekend. They’re the first two to the chalet. They immediately hate each other. An avalanche snows them in, completely closes them in.”

“The romantic comedy is these two people at each other’s throats stuck here, who gradually fall in love as they always should have. Wouldn’t that be good?”

The person was like, yes. I think she was writing it down.

Joanna: She wrote it down.

Tom: I think she did. So you can do that with anything and create that, but that is the kind of projects that have the greatest odds because they’re producible. It doesn’t take a lot.

The lower the price becomes, the lower the difficulty of making something becomes. The easier it is to say yes, and the harder it is to say no, to some degree.

That said, have a log line, number one. A log line is just a couple sentences, two or three sentences.

You know how we all hate writing blurbs? Okay, take that blurb that you have on the back of your book and that you have on your Amazon page, and cut it by two thirds, cut it by three quarters, and that is all you can say about your film.

Until you have that, you’re not really in the game. You need to have something super small and super simple.

Joanna: Just a little tip there for people. Just like we now can for sales descriptions, you can upload it to Claude or ChatGPT, and it will give you 20 log lines, 50 log lines, whatever you like. So that’s what I do. Only do that if you’re happy with the terms and conditions of these sites, but—

I certainly am finding this a lot more useful for my pitch material.

Tom: A great thing that AI can do, for sure, is to summarize something that you’ve already written. It’s very, very good for that. I totally agree with that.

So there are some other ways that you can have your project get more visibility. Some people talk about screenplay competitions. I am going to tell you that very few mean anything. Okay, and I will tell you the ones that do.

So ScreenCraft is closing down, Launch Pad, WeScreenplay. Those are all closing down. These were owned by a company called Coverfly, and it’s restructuring the way it does its business.

So a lot of screenplay competitions are dying, and a lot of the ones that still exist, like nobody in a place to buy a screenplay and to make a film are reading those scripts.

The ones that do matter, number one is the Nicholl Fellowship. That is the absolute number one. The screenplay that wins will be read by a lot of people in this town and a lot of people around the world.

Screenplays that even make it into the semi-finals or finals, that is a feather in your cap. That is a calling card that you can use to go out there.

There’s a website called TrackingB.com. The TrackingB, which stands for Tracking Board Contest, is absolutely legit. Hollywood, in particular, pays attention to scripts that win that or make it to the top of that.

The Austin Film Festival, the AFF, that screenplay competition is very well regarded and does mean something. There’s a screenplay competition called The PAGE.

Then there is Sundance and Raindance, both have competitions and fellowships and all sorts of things. They’re a fantastic resource. You should familiarize yourself with them. Also South by Southwest.

Those are the ones that are legit and have some amount of people that are legitimately looking for scripts to produce reading. So anything else, I would say, save your money. Don’t give them the entry fee because I don’t think it’s going to mean a lot.

Joanna: There’s a lot of them that charge. What about these pitch things? So obviously, I’m going to London Screenwriters’ again next month, and there’s a PitchFest, and there’s sort of 50 producers, execs, agents. It’s like speed dating, five minutes. It’s absolutely terrifying.

Last year it was ridiculous, and I was just the complete rabbit in the headlights. It was very out of my comfort zone. This year I’m going again, and I think I’m going to be a lot more relaxed.

So do you think those [PitchFests] are worth doing?

Tom: They vary just as much as screenwriting competitions. Some of them, like nobody on that panel is going to have any interest. I’ve been on those panels, and I can tell you, I’m doing a favor for somebody to sit there and listen to people pitch me.

Joanna: Oh, they’re not a panel. It’s like, you get five minutes one-on-one, and you do that as much as possible.

Tom: Okay, okay. I know that. I know that format as well. You never know, so I can’t really say no, but I’ll say that, much like speed dating, it’s a low percentage game.

Joanna: Fair enough. Fair enough. I did speed dating back in the day.

Tom: You’ve got to kiss a lot of frogs. So I wouldn’t say no to that, even if it’s just to have the pressure of pitching and pitching repetitively, which helps you learn how to do that. Pitching is absolutely a skill that you are not taught as a novelist, and you must learn as a screenwriter.

I went to 20Books Vegas two years ago, and this year I was a speaker at Author Nation, and I’m going to be a speaker at a bunch of other things this year, and people are like, “Well, you have one book out? How are you all of a sudden doing all this sort of stuff?”

I said, well, I’m used to pitching. I can pitch myself. I can pitch things. I have training in that, really. That’s super important.

Joanna: Also you’re incredibly successful, and everyone wants to talk to you.

Tom: That’s fine. I mean, sometimes you get blown off by people like Jo Penn, who says, “No, I don’t have time for lunch,” and then figures out, “Oh, wait, I know who you are.”

Joanna: “Oh, yes, maybe I’ll hang out.” Just for people listening, I didn’t know who Tom was. Luckily, I read his book, and it was amazing, and that’s how we kind of connected. Then I realized he was this big name screenwriter, so it was an interesting connection.

That’s unlikely to happen to me multiple times, and I’ll just suddenly meet this director. Although here is a question, I am getting pitched by so many screenwriters turned novelist, and I was wondering—

Is this because of the writers’ strike a few years ago and everyone just decided to write their novel?

Tom: Yes. I was I was going to say that. I actually got sidetracked at one point, but I was like, the Hollywood studio system did me a huge favor in shutting down and preventing me from writing screenplays for six months last year during the Hollywood Writers’ Strike.

It closed down the entire business. People lost homes, people lost apartments. People had to leave the business. It was a really, really tough time.

For me, I was like, oh, my God, I can actually finish the novel now. I can actually start moving in this direction that I’ve wanted to move in for so long. Thank you very much. It was very kind of you to do that.

Joanna: There is a lot now. You must have been quick off the mark because I’m getting them every day now. Every single day, people in various Hollywood things sending their novels. It is very, very interesting.

We don’t have much time left. I could talk to you forever, but I do want to ask you about AI because obviously part of that writer strike was around the clauses and use of AI.

Film has used different technologies for many, many years. James Cameron is famously working with Runway. There’s special effects. Film already uses AI, but it’s moving into a lot more areas. So what do you see ahead in terms of opportunities?

Will cost come down? What will happen? Any thoughts [on AI in the film industry]?

Tom: Yes, I have a lot of thoughts on the matter. I think that we are in a time of profound technological change. We’ve been here before. We’ve been here many, many times before. I’m young, and I’m old enough to remember the advent of the word processor and the explosion of the personal computer.

Everybody who worked in the white out factory, they had to find another job. Everybody who worked building typewriters had to find another job. There is going to be people that are going to lose jobs because things are being automated out of their purview and automating them out of space.

It’s not really something that we need to fear as creatives. Almost everything that we’re looking at is not a thing that is going to replace us, it is a new tool that we’re going to be able to use in creating art and creating great art.

If you go to YouTube and type in “Hedra” and watch what they’re doing, you will see some stuff that is scaring a lot of people in my business. It’s a company that is doing amazing video production that is completely AI-generated.

Amazing facial animation and voice cloning work that is giving fairly photo realistic performances of AI actors. I know some actors that are like, there will be no human actors in the next 100 years.

I was like, no. Look at this and see how good can this get. It can get only so good. It can deliver a life-like performance, but it can’t give an earth shattering performance. It’s not going to change your life. It’s going to be good enough. It’s never going to be at that level of exception. At least that’s my belief.

The same thing goes for writing. If I had a job writing copy for websites, I would be very worried about my job. I think that is definitely something that AI can replace.

Crafting the stories that I can craft with my voice and my weird, twisted sensibility, I don’t think AI is ever quite going to be able to do that. As you’ve said many times on this podcast, it’s what you bring that is the differentiator. That is the thing that AI will never replace.

That is also why your readers buy your books. They’re buying it for that special JF Penn factor, that special thing. I think the same thing goes for my industry.

Joanna: I’m glad you said that. I do hope that it will bring down some costs in production. For example, I know here in Bath where they film Bridgerton and all of this kind of thing, they’re building these sort of digital interiors, or scanning the interior of the Georgian buildings so that the actors can be somewhere else.

They’re still acting in the room, but it’s just projected onto that green screen. So the future for actors may be that you don’t get to travel so much, you just have to act in another green room. A lot of them are used to that, I guess.

Tom: I mean, if you look at all of the Star Wars television series that are out recently, they all use the technology similar to that. Where not only are you acting on a 360-degree cyclorama screen, but you are in real time.

You’re not having to imagine what the green screen is showing. You’re seeing what the actual surroundings of you are. Absolutely amazing.

There are AI right now that can already dub into foreign languages and do great work with not just subtitling, but actually dubbing projects into foreign languages. That’s going to be a cost cutting exercise. There’s going to be a lot of stuff that can really, really bring down the cost.

The fact of the matter is, you are maybe going to take a 100-person crew and make it an 80-person crew. You can maybe take a 50-person crew and make it a 30-person crew.

There are still so many jobs that are still going to require people and skilled artisans in their particular fields. I think there’s a limit to how much AI is going to be able to save us, but it will be able to save quite a bit.

Joanna: Fantastic. So just briefly—

Tell us about The Year of the Rabbit. Also, where can people find you and your books online?

Tom: Listen, my first novel out of the gate, I’m super happy that it’s gotten the response that it’s gotten. Jo, you were very kind to blurb the book for me. I really appreciated that.

Joanna: It’s a great thriller, for people listening.

Tom: I will say that I’m Amazon exclusive. So it’s T.D. Donnelly, D, O, N, N, E, L, L, Y. Year of the Rabbit is the name of the book. If you like action thrillers, if you like spy thrillers, if you like thrillers with a lot of character and a very unique lead character, I highly recommend you check it out.

Should I give a quick blurb of it?

Joanna: Yes. Why not?

Tom: Year of the Rabbit is about Malcolm Chaucer. Malcolm Chaucer is the world’s greatest interrogator. He is a human lie detector that can read every micro expression on your face to know whether or not what you’re saying is a truth or a lie.

He knows this because he is a deeply broken man who, for eight years, was tortured in North Korea and suffers extreme PTSD. That is his super power. That is why he is hypervigilant and able to notice all of these things.

Well, during a routine interrogation in New York, he finds out that the person that these people are looking for is his ex-wife. That starts him down a road of suddenly being hunted himself, as well as she is, by nameless assassins.

Actually, everybody in New York that that has access to a computer is suddenly told a million dollar bounty on his head. Can he figure out truth from lies? Can he figure out who wants to kill him? And can he figure out the secret that is the Year of the Rabbit?

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, thanks so much for your time, Tom. That was great.

Tom: Oh, let me just say, TDDonnelly.com is the website. That’s the other thing. Thank you.

Joanna: Thank you.

The post From Hollywood To Novels: TD Donnelly On Screenwriting, Adaptation, and Storytelling That Lasts first appeared on The Creative Penn.

When writing a Fall Arc, writers get to explore the slow, often heartbreaking process of moral or emotional decline. In this type of Negative Change Arc, the characters’ refusal to change or acknowledge their flaws becomes a central theme. They hold onto a Lie—a deeply ingrained belief or limited perception of the world—that drives their actions and decisions. Over time, this self-deception evolves into something darker, affecting not just their own choices, but their relationships with others. Understanding how to write a Fall Arc can help you create a character whose downfall feels deeply tragic and engaging.

When writing a Fall Arc, writers get to explore the slow, often heartbreaking process of moral or emotional decline. In this type of Negative Change Arc, the characters’ refusal to change or acknowledge their flaws becomes a central theme. They hold onto a Lie—a deeply ingrained belief or limited perception of the world—that drives their actions and decisions. Over time, this self-deception evolves into something darker, affecting not just their own choices, but their relationships with others. Understanding how to write a Fall Arc can help you create a character whose downfall feels deeply tragic and engaging.

The Disillusionment Arc is one of the most powerful and emotionally resonant transformations a character can undergo. At its core, this arc is about awakening—shedding comforting illusions to face a stark and often uncomfortable Truth. While it shares similarities with the Positive Change Arc, the Disillusionment Arc doesn’t always lead to a hopeful resolution. Instead, it challenges both the characters and the audience to grapple with the weight of reality. However, despite its seemingly bleak nature, the Disillusionment Arc isn’t inherently negative. It reflects a fundamental aspect of human growth: the process of seeing the world as it truly is and deciding what to do with that knowledge.

The Disillusionment Arc is one of the most powerful and emotionally resonant transformations a character can undergo. At its core, this arc is about awakening—shedding comforting illusions to face a stark and often uncomfortable Truth. While it shares similarities with the Positive Change Arc, the Disillusionment Arc doesn’t always lead to a hopeful resolution. Instead, it challenges both the characters and the audience to grapple with the weight of reality. However, despite its seemingly bleak nature, the Disillusionment Arc isn’t inherently negative. It reflects a fundamental aspect of human growth: the process of seeing the world as it truly is and deciding what to do with that knowledge.

[From KMW: I’m taking a quick sabbatical this week. I’ll be back next Monday with a post/podcast about “The Disillusionment Arc in Storytelling: A Powerful Tool for Character Growth.” Until then, I hope you enjoy this short post on the important topic of how to write subtext in fiction!]

[From KMW: I’m taking a quick sabbatical this week. I’ll be back next Monday with a post/podcast about “The Disillusionment Arc in Storytelling: A Powerful Tool for Character Growth.” Until then, I hope you enjoy this short post on the important topic of how to write subtext in fiction!]

Great character arcs are built on transformation, and one of the most powerful frameworks for understanding this journey is the four stages of knowing in character arcs. These stages map a character’s growth through initiation to enlightenment to integration in a way that feels deeply satisfying to readers. Why? Because it is yet another way in which the shape of story mirrors the patterns of real life. Once you can see how plot structure challenges characters to grow (sometimes successfully, sometimes not), you can more consciously craft resonant character arcs.

Great character arcs are built on transformation, and one of the most powerful frameworks for understanding this journey is the four stages of knowing in character arcs. These stages map a character’s growth through initiation to enlightenment to integration in a way that feels deeply satisfying to readers. Why? Because it is yet another way in which the shape of story mirrors the patterns of real life. Once you can see how plot structure challenges characters to grow (sometimes successfully, sometimes not), you can more consciously craft resonant character arcs.

Need a writing buddy? A critique partner? A beta reader? Here’s your stop!

Need a writing buddy? A critique partner? A beta reader? Here’s your stop! But sometimes it can be difficult to find someone willing to read your work who is also a good fit for you and your writing.

But sometimes it can be difficult to find someone willing to read your work who is also a good fit for you and your writing.

From KMW: If you’ve been following my work, you know how much I emphasize the power of Flat Arc archetypes in storytelling—characters like the Child, Lover, Ruler, Elder, and Mentor, who don’t undergo drastic change but instead remain true to their core nature, influencing the world around them.

From KMW: If you’ve been following my work, you know how much I emphasize the power of Flat Arc archetypes in storytelling—characters like the Child, Lover, Ruler, Elder, and Mentor, who don’t undergo drastic change but instead remain true to their core nature, influencing the world around them.

Recent Comments