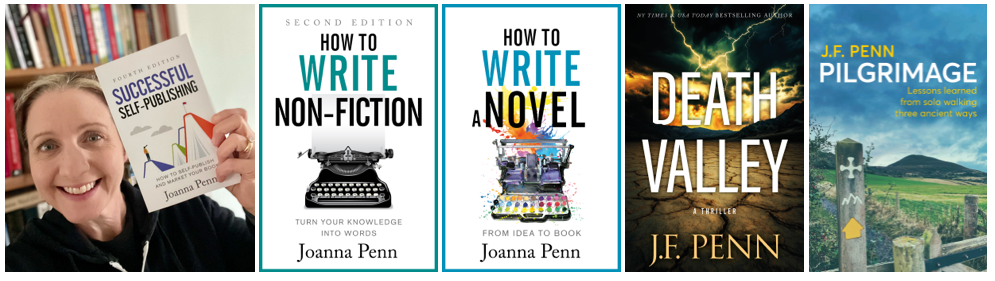

Book Marketing Tips For Fiction And Non-Fiction Authors With Joanna Penn

What marketing principles remain true regardless of the tools you use? What are the different ways you can market your book, whatever your genre? In this episode, I share two chapters from my audiobook, Successful Self-Publishing, Fourth Edition.

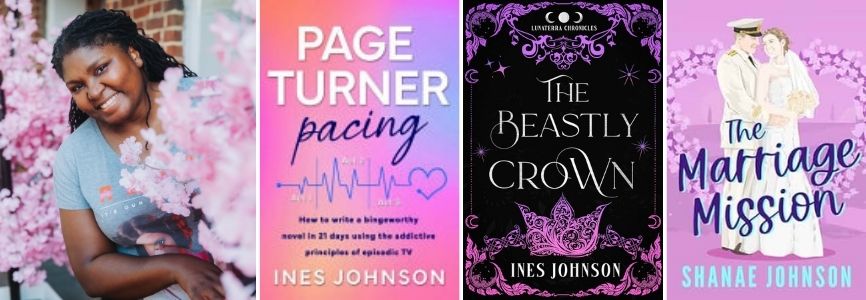

In the intro, Pricing strategies on The Biz Book Broadcast;

What to do Three Years Before your book launch [Dan Blank]; ChatGPT GPT5; Gemini Storybook, ElevenLabs Music.

Plus, AI-Assisted Artisan Author webinars in September; Gothic Cathedrals; British Pilgrimage [Books and Travel]; The Buried and the Drowned – J.F. Penn.

Today’s show is sponsored by ProWritingAid, writing and editing software that goes way beyond just grammar and typo checking. With its detailed reports on how to improve your writing and integration with writing software, ProWritingAid will help you improve your book before you send it to an editor, agent or publisher. Check it out for free or get 15% off the premium edition at www.ProWritingAid.com/joanna

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

J.F. Penn is an award-winning, New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of thrillers, crime, horror, dark fantasy, short stories and travel memoir, as well as writing non-fiction for authors as Joanna Penn. She’s also an award-winning podcaster and creative entrepreneur.

- Marketing principles

- 15 ways to market your book

These chapters are excerpted from Successful Self-Publishing, Fourth Edition by Joanna Penn, available in ebook, audiobook, and print formats.

Marketing Principles

If you ask most authors about book marketing, they’re likely to grimace, shake their head, and sigh…

We became authors because we love to write, but if you want your books to sell — regardless of how you choose to publish — at some point you’ll need to embrace marketing as part of your author journey.

In this chapter, I’ll go through marketing principles that will be useful no matter how the industry changes. But first, let’s cover the question everyone always asks.

Do I have to do my own marketing? Can’t I just outsource it all?

There are many people and services you can hire for aspects of book marketing, but consider these questions:

- What specific area of marketing do you want to outsource?

- Is it worth doing at all?

- Is it worth paying for?

- What return on investment (ROI) are you expecting?

- Is this service short-term or long-term and how might that affect your budget?

Book marketing is not one thing, so you need to first consider what exactly you want to outsource. For example, setting up and running Amazon Ads is a different skill to pitching magazines and podcasts for interviews.

You also have to consider whether you even want to start something you might not sustain.

- Is it worth starting a TikTok channel if you hate making videos?

- Is it worth starting your own podcast when it might be a year or so before your listenership grows to a decent size?

- Is it worth paying a PR professional to get you interviews in magazines when you’re just starting out, you’re unsure of your brand, and there is no obvious return on investment?

- Do you want to keep paying people for months and years? Or could you spend some of that money learning new skills and building your own sustainable marketing strategy?

If you want to hire a professional, be specific about the tasks and your budget, as well as timeframe. For example, ‘Run Meta Ads for three months to the first book in my fantasy series’ or ‘Pitch media outlets for three months around my non-fiction self-help book on dealing with anxiety.’

If you want help with book marketing, you can hire vetted professionals from the Reedsy Marketplace and find people on the Alliance of Independent Authors Partner Member list.

While I have hired specific people over the years for short-term marketing campaigns, I primarily do my own marketing. Here are some principles that will help you if you choose to do the same.

(1) Reframe marketing as creative sharing

Many authors feel that marketing and sales are negative in some way, but that attitude makes the whole thing more difficult. Whether you have a traditional book deal or you self-publish, you have to learn to market if you want to sell books. So, it’s time to reframe what marketing is!

Marketing is sharing what you love with people who will appreciate hearing about it.

Marketing is not shouting ‘buy my book’ every day on social media or accosting readers in bookstores or at author events. You should never be pushing anything to those who are not interested. Instead, try to attract people who will love what you do once they know about it.

We’re readers too and we all love to find new books to immerse ourselves in, so think about other readers in the same way.

If you’ve written a great story in a genre that you love, why would you ever be embarrassed about promoting it ethically to fans of that genre?

If you’ve written a book on gluten-free weight loss, it’s likely that you’ve achieved success with your method. You’re trying to help people, so why wouldn’t you want to spread the word?

Once you change your attitude, the whole marketing landscape shifts. It becomes far more positive when you’re sharing things you love and attracting like-minded people.

If you start enjoying marketing and make it a sustainable part of your creative life, you’ll find it works a whole lot better — and might even be fun!

(2) Focus on the reader

Writing is about you. Publishing is about the book. Marketing is about the reader.

When we write, we are in our own heads. We’re thinking about ourselves. But when we publish and market, we have to switch our heads around to the other side of the equation and consider the person who reads or listens to the book and what they want out of the experience.

Step outside your own head and ask these questions: Who is my ideal reader? What emotion or outcome do they crave? What problem am I solving, or what entertainment experience am I providing?

The answers will help you with the words and images you use in marketing to attract the right readers.

(3) Own your platform

When you write a book, you need to have somewhere to direct people so they can find out information about you and what you write.

There are many options for building your home on the internet, but an important consideration is who owns the site you build on.

If you use a free site, it’s owned by someone else, whereas if you pay for hosting, you control it. You can back it up and make sure it’s always available. This matters because things change over time.

Some authors let their publisher build a website for them, but what if you begin working with a different publisher?

Some authors just use a Facebook page, but what about when Facebook changes the rules (as they have done several times over the years)?

Some authors use a free website service, but if that company disappears or gets bought or decides your book isn’t appropriate, what happens to your site?

If you’re serious about writing and selling books for the long-term, then consider owning your website.

You can do all kinds of other things to market your book, but at least you’ll always have somewhere to send people.

Equally, it’s important to build your own email list of readers who like your books, because again, who knows what will happen in the future with the book retailers or the publishers you use?

If you have an email list of readers, you can always sell books whatever changes come along.

You can find the services I use and more tips at: www.TheCreativePenn.com/website-email-help

(4) Build a cohesive author brand

Branding is your promise to the reader. It’s the words, images, and emotions that surround your work and the way readers think of you.

Many authors consider using a pseudonym, or different names if they write books aimed at separate audiences. I write under J.F. Penn for my fiction and memoir and Joanna Penn for my non-fiction for authors. I have different types of books with almost completely different audiences, so I need separate brands.

Book cover design also expresses brand and differs by genre. You should have some idea of the books and authors that are similar to yours.

Examine their book covers and the color palette they use, as well as their author websites.

- What words, images, and colors do they use?

- What emotional resonance does their brand present?

- How does it make you feel as a reader?

Now try to apply those principles to your own author brand.

If you’re struggling with brand, don’t worry. It will emerge and become clearer over time as you find your voice and attract an audience over multiple books.

When I started out, I published everything under Joanna Penn, and eventually split my author brand to make things clearer for readers, as well as myself. But it took five books and several years before I understood that was the right decision for me.

(5) Find marketing that fits your personality. Double down on being human.

If you want a sustainable career as an author, you need to consider what kinds of marketing you can consistently do over time. You can’t fake it or force yourself to do things you hate. Marketing needs to fit with your personality and your lifestyle, and that will differ for everyone.

You also need to be personal and, in an age of AI, double down on being human. The more you share authentically, the more people will get to know, like, and trust you, and the more likely they are to want to buy your books.

Of course, you have to draw your personal line in the sand. I don’t share pictures of my family on social media, and some authors use codenames for their children so they can talk about being a parent while still protecting privacy.

You also need to know what’s best for managing your energy. I’m an introvert, so I find in-person events and group things difficult, and I tend to avoid in-person marketing. I also don’t watch video online so I produce little of it, and I don’t do short-form video like TikTok or Instagram Reels.

I listen to a lot of podcasts and audiobooks, so audio marketing is my primary channel. I have two shows, The Creative Penn Podcast for writers, which markets my Joanna Penn books, and my Books and Travel Podcast, which is for my J.F. Penn side. The shows go out on audio podcast feeds and also onto my two YouTube channels.

I also like taking photos, so I use Instagram @jfpennauthor and also share on X @thecreativepenn. I share pictures of my travels and what I’m up to for research, and my cats, and over time, I’ve become a lot more open about what I like.

For example, I’m a taphophile. I enjoy walking around graveyards and I like ossuaries and crypts, as well as art history and cultural aspects of death and memento mori. It turns out there are many people with Gothic leanings like me, and people even send me photos of their favorite graveyards from all over the world now.

Sharing details about your interests might not be an obvious path to book sales, but attracting readers slowly over time in an authentic way can underpin a sustainable long-term career.

(7) Balance short-term and long-term marketing

New authors often focus on the launch of their latest book, but most indie authors and publishing companies make more money from the ‘back list,’ older books with more reviews and a sales history. A book is always new to someone who has just discovered it, and that ‘new’ book might not be your latest release.

Short-term marketing is a good option for new releases, for campaigns like a Kickstarter, or if you want to push a first-in-series book from your backlist to introduce people to your work. These kinds of campaigns usually include some form of paid marketing, which can drive a sales spike that drops once you stop pumping money and energy into it. For most authors, this is not sustainable.

Long-term marketing is more about building evergreen assets that drip sales every day. If you want a long-term career as an author, you need to think about building a sustainable baseline income, money that comes in from your books consistently every month without you having to keep paying for it.

Successful long-term marketing requires more books on the market, more streams of income, more readers on your email list, and consistent content marketing of some kind. It takes time to build but is worth the investment if you want a long-term career. The most successful authors combine these two approaches with sustainable marketing strategies.

(8) Measure the success of your marketing

If you’re not measuring the results of a promotion, how do you know if it worked?

Marketing should ultimately result in sales, and if you’re self-published, you can measure this easily, as you get daily sales figures from the self-publishing platforms. You can also check your rankings on the stores and take screenshots before and after the promotion to check results.

This is why I prefer online marketing to traditional media and PR. If you have a clickable link associated with your promotion, you can track results and understand what works and what doesn’t.

When I first started out, I had national TV, radio, and newspaper coverage, but it had no noticeable impact on my book sales. These days, I can pay for a BookBub ad or email my list with a link and see the resulting direct sales spike. Measure promotion results, rather than basing your opinion on assumptions or ego metrics (likes and comments rather than sales).

Track what matters to your author business: sales, income, profit, email subscriber growth, number of reviews, and use those to guide your next campaign.

(9) Build community and collaborate with other authors

Some people say being a writer is lonely, but that is a choice, because there are so many different communities you can join in person or online. You can also build one of your own.

People want to belong to something, they want to be part of a group, and together, we can achieve more and the journey will be a lot more fun!

I’m a member of the Alliance of Independent Authors, which has a thriving community online and also meets up in person at book industry events. I speak at and also attend lots of conferences, including Author Nation, the biggest indie author conference in the world. I’m also a member of several Facebook groups, for writing craft and author business, where I check in every few days to see what’s going on.

I also have my own Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn, where I share behind-the-scenes details about running an author business.

Not every group is for every person, of course, so you must find the places that feel right for you. But give things a try, be generous and helpful and a good community member, and you will find author friends.

Being part of a community can also lead to marketing ideas and opportunities — for example, collaborating on email newsletter swaps or book recommendations, joint promotions, multi-author bundles and box-sets, and cross promotion on podcasts and social media.

Remember, as with writing, marketing gets easier with practice. Start small, be consistent, and focus on the principles that never change, even as the tools and platforms evolve over time. Marketing your book is not a onetime event but an ongoing process, so take one step at a time and iterate as you go.

Experiment to find what works best for your personality and lifestyle — for each book and at each stage of your author journey. Once you choose a strategy, commit to it for the long term, and you’ll build an audience and book sales in a sustainable manner.

Different ways to market your book

I’m often asked, “What’s the one thing I should do to market my book?”

Annoyingly, the answer is: “It depends.”

It depends on you and your personality, your book, your budget, your goals and definition of success, as well as market conditions.

There is no silver bullet, no magic formula that works for every book and every author every time.

Here are some ideas you could use to get started. You can find books and courses on each of these, so if you’re drawn to a particular method, dive deeper, learn more, experiment, and see what works for you.

(1) Write more books

If you look at lists of the best-known, best-loved, and richest authors, they generally have a lot of books and have been publishing for many years.

We are writers. We write. So it makes sense that the best marketing starts by writing more books.

One book is not enough to establish an author career, if that’s what you want. Even if a single book breaks out and becomes the ‘must read’ of a particular year, it doesn’t mean that readers will buy the next book from that author. They may not even remember the author’s name. But if you have three or four books that offer the same type of experience and if a reader reads them all, you’re likely to have won a fan who will actively look for your next book.

Every time you launch something new, more people have a chance to find out about your work. Every time you write in a new genre or publish in a new format, different kinds of people discover you. Some of them will go on to buy or read or listen to more of your work, join your email list, or support you in other ways.

For example, perhaps you found me through my show, The Creative Penn Podcast, then you downloaded my Author Blueprint, then you listened to my craft audiobook, How to Write a Novel, and now you’ve bought this book.

Or perhaps you found my first thriller, Stone of Fire, as a free promotion through BookBub and then read all the others in the ARKANE thriller series, before supporting my Kickstarter for book 13, Spear of Destiny.

I have a lot of books across many genres written over almost twenty years, so there are many different paths into my body of work, which grows over time as I continue to create. This is definitely my favorite way to market!

By producing new work, you will develop an audience over time, as well as finding your voice and increasing your creative self-confidence. You will become a better writer with every book, so the chances of readers loving your work will also increase.

You can also experiment with different forms. Try short stories, short non-fiction or novellas, as well as novels and full-length non-fiction or memoir. Once you have enough material, consider putting multiple books together in a boxset or bundle. There are so many possibilities!

(2) Write multiple books in a series and link them together

Existing customers will buy more books from an author if the new book promises the same experience delivered in previous books, whether they are fiction or non-fiction. This is why series are so powerful.

As a reader, there are some authors I pre-order from because I love a particular series, even though I might not read the other books they have. I’m loyal to the series characters, even more so than the author, because I want to know what happens next and I get an (almost) guaranteed experience.

For non-fiction, there are authors who I trust and whose books I buy because I know they will be interesting, informative, and inspiring.

If a reader discovers and loves your series when you release book five, they are likely to go back and buy the rest of them, which means more income for you and more satisfaction for the reader.

A novel in a series is also faster to write than a stand-alone title, as you don’t have to reinvent the characters and the world, you just need to find your plot and start writing.

If you write literary fiction or enjoy writing stand-alone books, consider the themes that tie your books together and think of ways to encourage people to move between them. You can create interconnected stand-alones — for example, books set in the same universe or linked by theme — so recommendation engines connect the dots.

Your options expand the more books you write. I have several fiction series, with the main being my ARKANE thrillers, but I also have stand-alone stories like Catacomb and Death Valley. For non-fiction, I have books for authors in a series, but I also have a memoir, Pilgrimage, which is a stand-alone.

While it’s easier to market books in a series, I certainly understand the creative urge to write all kinds of different things!

(3) Optimize your metadata

Metadata is the information about your book, rather than the book itself. It includes your title, subtitle, series title, sales description, keywords, categories, and your author bio. Some platforms also include data points like reviews and sales history so their recommendation engines understand where your book fits into the ecosystem.

We went through this in chapter 2.3, but metadata is a key aspect of marketing. If you find your marketing efforts aren’t getting the results you want, make sure you’ve made the right metadata choices for your book, and change things over time to keep it fresh.

(4) Use different price points, strategic discounting, and value bundles

The more books you publish, the more flexibility you have with pricing. You also won’t be so emotionally attached to any individual book, which makes it easier to play with pricing.

If you’re in Kindle Unlimited for your ebooks, you get five free days for promotion every ninety days. If you’re wide, you can set the price to free on all other stores, and Amazon will price match. My first ARKANE thriller, Stone of Fire, is free on all ebook stores, which brings people into the thirteen-book series.

You can also use limited-time discounts — for example, drop the price to 99 cents and promote the sale, introducing your books to new readers who might be hesitant to try a new author at full price.

You can also use fan pricing and launch pricing interspersed with full-priced books, rewarding your most loyal readers while still capitalizing on launch momentum and algorithms.

If you have books in a series, you can sell bundles at a great price, giving the reader value and putting more money in your pocket, especially if you sell direct.

(5) Build an email list by offering a reader magnet, then stay in touch

Make sure you have a link at the back of your book to a free reader magnet, something that the reader wants, if they give you their email address.

For my non-fiction, I offer my free Author Blueprint ebook at: www.TheCreativePenn.com/blueprint

For fiction, I offer a free thriller at: www.JFPenn.com/free

The call to action for both is in the back of every book, and also on my websites, podcasts, and social media, and people sign up for these lists every day.

Once people are on your email list, stay in touch. Let them know about new releases and giveaways, and draw them closer to you by sharing personal photos, book recommendations, or behind-the-scenes research. If you’re unsure what to email about, join a few successful author lists and see what they’re doing.

There are lots of email services. I use and recommend Kit (previously ConvertKit) at: www.TheCreativePenn.com/kit

(6) Build a ‘street’ team or ARC team

This group is a subset of your main email list, and is made up of readers who want advance reader copies (ARCs) and who are happy to promote, write reviews, and share on social media.

Some authors have incredibly active ARC teams with extra swag and giveaways as well as events. But you can keep it simple. I have an automated email inviting people to my Pennfriends list that goes out after six months on my fiction email list. They get early access to some new books and also free backlist books and many of them write reviews.

You can give away ebooks with watermarks through BookFunnel if you want to protect the files.

(7) Ask for reviews to build social proof

You don’t need an ARC team to get reviews. You can just ask readers by including a call to action at the back of your books — for example, “If you enjoyed the book, please leave a review on the store where you bought it. Thank you.”

Many authors obsess about getting reviewed in traditional media, but it’s more important to build up social proof on the online stores or on Goodreads (owned by Amazon). This evidence of reader approval will help you get promotions. For example, BookBub requires a certain number of reviews and a high average review rating before accepting a book for promotion.

Free books are the easiest to get reviews on, so if you’re struggling to get started, put your book on a free promotion and do some advertising to get downloads.

(8) Use social media

There are lots of different social media platforms, and each has its own rules and tactics, as well as its own demographic. You cannot be successful on all of them, so focus on one or two, learn the right skills for that platform, test out different content, and lean into what works.

The rise in beautiful print editions, particularly for fiction, has benefitted from the trend in social media video, with TikTok videos driving many books up the bestseller lists.

While social media marketing can be ‘free’ in terms of money, you will certainly pay with your time. All the platforms reward regular content and engagement, which works for some authors, but not for others.

There are authors who use social media effectively to drive massive sales and success online, but they put a lot of work in, or they hire people to help. Find successful authors in your niche to follow and model what they do if this is an area you want to focus on.

Personally, I’m not a huge fan of social media and use it more to prove I’m a human, sharing photos of my life and book research on Instagram @jfpennauthor. I also use X @thecreativepenn as a news platform where I learn about new technology and find content to share on my podcast. I also have Facebook pages, Pinterest boards, and a LinkedIn profile, but I’m not particularly active on any site.

(9) Use content marketing

Content marketing is my favorite form of marketing, and I’ve built my business around it. It’s essentially offering free content in your preferred format that educates, inspires, or entertains, and attracts people who might also be interested in buying your books, products, and services.

For non-fiction, I’ve been blogging and podcasting at www.TheCreativePenn.com since 2008. I also have a YouTube channel @thecreativepenn.

For fiction, I have free short stories, audio and video on YouTube @jfpennauthor, and I also have my Books and Travel Podcast and blog.

This content can also be a stream of income. For example, YouTube videos can be monetized with ads, podcasts can include sponsorships, and Substack newsletters can offer a paid tier alongside free information.

Providing quality content over time builds up your site and you personally as an authority and trusted source in a niche. The content remains on your site and you can build up a body of work that continues to attract people over the long term.

Content marketing often requires longer form pieces than social media. I create podcast interviews and episodes of thirty minutes to an hour weekly, instead of multiple thirty second videos on social media every day. No one has time for both things, so choose what suits you and your personality.

To help you decide, ask yourself this question: What do you currently consume?

I walk a lot and listen to podcasts, and I rarely scroll social media, so it makes sense for me to focus on audio-first content marketing. I also travel and take a lot of photos for book research, which I enjoy sharing on my blog and podcast at BooksAndTravel.page.

If you watch a lot of TikTok videos, or you love scrolling on Pinterest or reading articles on LinkedIn, then your own daily preferences should give you a hint as to what would suit you as a creator.

(10) Pitch for podcast or YouTube interviews

If you don’t want to build up your own content marketing site, you can pitch podcasters, YouTubers, or bloggers with your book, and appear on their platforms.

Do your research to find shows that will be a great fit for your work, then send an effective pitch to a few specifically targeted creators.

These interviews are never about selling your book. They are all about giving incredible value to the audience, which will make them want to find out more and naturally lead to book sales. Include five bullet points in your pitch about what exactly the audience will find useful, and make it easy for the host to understand why you’re a good fit.

This targeted approach will lead to much greater success than sending hundreds of pitches with a basic press release about your book.

(11) Pitch other media for interviews

Traditional media still has significant reach and authority, although it’s usually more for brand-building than direct sales.

Start by pitching local newspapers, TV, and radio, as they are often looking for local success stories and are easier to access than national media.

Research which journalists cover your topic or genre at each outlet, and look for those who have written similar stories.

As with podcast pitches above, you need a hook beyond ‘I wrote a book.’ Connect your pitch to current events, trends, or a unique personal journey. Make sure you have a professional headshot, book cover image, short and long bio, and sample interview questions ready to send.

(12) Try paid advertising: pay per click

A lot of marketing takes time rather than money, but you can get traffic — and sales — more quickly if you use paid ads.

The most popular and effective pay-per-click ads for authors are Amazon Advertising, Meta Ads for Facebook and Instagram, as well as BookBub Ads.

Choose which audience to market to, either with keywords or target audiences, set a budget, design the images, and let the ads run, paying per click or per impression. You’ll need a period of testing and time to monitor and adjust ads, and you may find you need to refresh the images or ad copy over time.

Most successful indie authors use paid advertising of some kind to drive traffic to their books, but it’s certainly not necessary. You need patience to learn the specific platform, test, monitor, analyze, and adjust ads. Or you can outsource your advertising, paying someone to run them as well as paying advertising platform costs.

This approach is most effective when you have multiple books in a series, as cost per click can be expensive if you only have one or two books.

I use Amazon Ads for some non-fiction books and rely on auto-ads using Amazon’s own algorithm to manage them. I also use Meta and BookBub Ads as part of short-term campaigns at launch or for promotional spikes.

(13) Try paid advertising: email newsletters

The most popular email marketing newsletter services are BookBub Featured Deals, and Freebooksy, Bargain Booksy, and other options run by Written Word Media.

With these services, you pay to submit your book for a genre promotion, and they email their targeted list of readers with a link to your book, along with many others. Hopefully, you get enough sales to justify the cost.

To be clear, you are buying a place on an email blast to readers. You are not buying a list of email addresses. Never do that as it violates anti-spam regulations.

(14) Try local, in-person marketing

While online marketing can be effective for reaching readers all over the world, in-person marketing can be rewarding for connections with readers and other authors, and can result in significant sales.

In-person marketing might include speaking at a local networking event or school assembly, literary festival, book club, or library, as well as having a book stall at conventions, conferences, local fairs, and markets.

Investigate options in your area and balance the costs of setting up a stall and ordering physical stock with the potential for income and local marketing reach.

(15) Collaborate with other authors on joint promotions or events

Even the most prolific authors can’t satisfy their readers alone, so it’s good to develop a network of authors in your genre, or those with a crossover audience. You can help promote each other’s books and do joint events and promotions together to keep readers reading in your niche. You’ll also make author friends, and this support is critical for long-term success.

There are lots of options for collaboration, from co-writing books, cross-promotion in email newsletters, to multi-author bundles, joint online launch parties, and social media sharing. If you’re new or want to expand your network, BookFunnel offers different kinds of group promos.

I collaborate with authors in lots of ways and often build relationships and attract opportunities through my podcast interviews. I’ve co-written fiction and non-fiction books, appeared on other shows, promoted authors to my email lists and on social media, and also collaborated on joint author in-person events.

I’ve also done bigger paid ad campaigns. In 2014, I was part of the Deadly Dozen, where twelve mystery and thriller authors hit the New York Times and USA Today bestseller lists with our multi-author ebook boxset. We all ran different promotions as well as jointly paying for advertising, and we sold over 100,000 ebook bundles and attracted many readers to our email lists.

If you want to collaborate with other authors, be generous and helpful and you will attract opportunities. Volunteering at author conferences can also be a great way to build your network.

Marketing is an ecosystem

It takes time to build out a sustainable marketing approach that keeps your books selling every month over many years.

You can pay for advertising right now and you will drive traffic to your books and hopefully sell some, but as soon as you stop paying, the sales will drop off.

The best approach is to think of marketing as an ecosystem made up of multiple aspects around you and your creative work.

What do you enjoy doing and what kinds of marketing can you sustain over time?

The most successful authors build marketing into their regular routine rather than treating it as a separate, painful task to check off as required for each book launch.

Marketing is about connecting people with your books. When you genuinely help people find stories they’ll love or solutions to their challenges, marketing becomes less about self-promotion and more about valuable service. It’s an important part of being a successful self-published author.

These chapters are excerpted from Successful Self-Publishing, Fourth Edition by Joanna Penn, available in ebook, audiobook, and print formats.

The post Book Marketing Tips For Fiction And Non-Fiction Authors With Joanna Penn first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn

There’s nothing quite like a scene that ends with a bang—or at least a purposeful beat that pulls readers deeper into the story. A well-crafted scene ending doesn’t just wrap things up, it launches momentum into the next scene, tightens your pacing, and deepens the emotional arc. Your scene might close in any number of ways, everything from a victory to a setback or a plot twist to a moment of quiet revelation. Whatever the case, scene endings create the impression that will (hopefully) carry readers into what comes next. Really, your writer’s toolbox doesn’t contain many tools more powerful than scene endings, yet they can be easily overlooked when it comes to tightening tension or strengthening overall story structure.

There’s nothing quite like a scene that ends with a bang—or at least a purposeful beat that pulls readers deeper into the story. A well-crafted scene ending doesn’t just wrap things up, it launches momentum into the next scene, tightens your pacing, and deepens the emotional arc. Your scene might close in any number of ways, everything from a victory to a setback or a plot twist to a moment of quiet revelation. Whatever the case, scene endings create the impression that will (hopefully) carry readers into what comes next. Really, your writer’s toolbox doesn’t contain many tools more powerful than scene endings, yet they can be easily overlooked when it comes to tightening tension or strengthening overall story structure.

In a world flooded with stories—books, shows, films, and endless social content—it’s easy to fall into passive consumption. But as writers and creatives, what we take in matters just as much as what we put out. To write with depth, clarity, and resonance, we must first learn to read more intentionally and watch with greater awareness. Intentional consumption isn’t about being rigid or “highbrow.” Rather, it’s about choosing stories that challenge us, feed us, and reflect the kind of storytelling we want, in turn, to create.

In a world flooded with stories—books, shows, films, and endless social content—it’s easy to fall into passive consumption. But as writers and creatives, what we take in matters just as much as what we put out. To write with depth, clarity, and resonance, we must first learn to read more intentionally and watch with greater awareness. Intentional consumption isn’t about being rigid or “highbrow.” Rather, it’s about choosing stories that challenge us, feed us, and reflect the kind of storytelling we want, in turn, to create.

We’ve all experienced it: a story that looks good on paper, features big-name characters, or starts with an intriguing premise—but somehow falls flat. Maybe the characters feel hollow, the plot drifts without purpose, or the ending lands with a thud. But what actually makes a story “bad”? Are there pitfalls you can look out for that can save your story? More importantly, how can you avoid these mistakes when writing or editing?

We’ve all experienced it: a story that looks good on paper, features big-name characters, or starts with an intriguing premise—but somehow falls flat. Maybe the characters feel hollow, the plot drifts without purpose, or the ending lands with a thud. But what actually makes a story “bad”? Are there pitfalls you can look out for that can save your story? More importantly, how can you avoid these mistakes when writing or editing?

Over the years, I’ve developed a set of terms that have become foundational to how I teach storytelling. A few I’ve coined myself, others I’ve adapted, and some I’ve simply emphasized so frequently they’ve become closely associated with my approach to character arcs, story structure, and theme. Whether you’ve followed my work through this blog or my books and courses, chances are you’ve come across many of these ideas and maybe even adopted them into your own writing process.

Over the years, I’ve developed a set of terms that have become foundational to how I teach storytelling. A few I’ve coined myself, others I’ve adapted, and some I’ve simply emphasized so frequently they’ve become closely associated with my approach to character arcs, story structure, and theme. Whether you’ve followed my work through this blog or my books and courses, chances are you’ve come across many of these ideas and maybe even adopted them into your own writing process.

These days, it’s easier than ever to write stories that look like stories. I’m talking about stories follow beat sheets, mimic bestselling formulas, and say all the “right” things. But more and more, I see authors tempted to make creative choices based on convenience rather than imagination or integrity. When that happens, we have to ask: are we saying anything real?

These days, it’s easier than ever to write stories that look like stories. I’m talking about stories follow beat sheets, mimic bestselling formulas, and say all the “right” things. But more and more, I see authors tempted to make creative choices based on convenience rather than imagination or integrity. When that happens, we have to ask: are we saying anything real?

There’s nothing like a sharp-tongued, quick-witted character to light up a scene—especially when the stakes are high or the tone is dark. From sarcastic sidekicks to roguish heroes, witty characters often steal the show. But when the humor feels forced or out of character, it can suck the life right out of a story. So why does some wit dazzle while other attempts fall painfully flat?

There’s nothing like a sharp-tongued, quick-witted character to light up a scene—especially when the stakes are high or the tone is dark. From sarcastic sidekicks to roguish heroes, witty characters often steal the show. But when the humor feels forced or out of character, it can suck the life right out of a story. So why does some wit dazzle while other attempts fall painfully flat?

Recent Comments