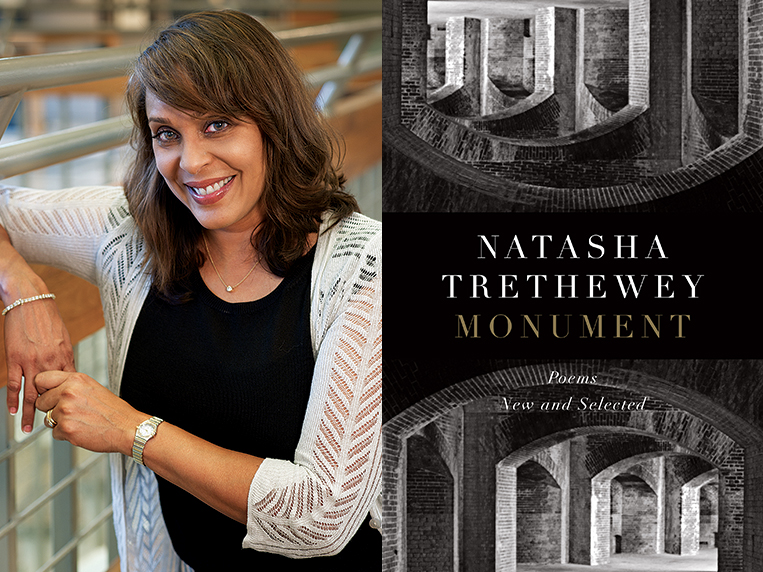

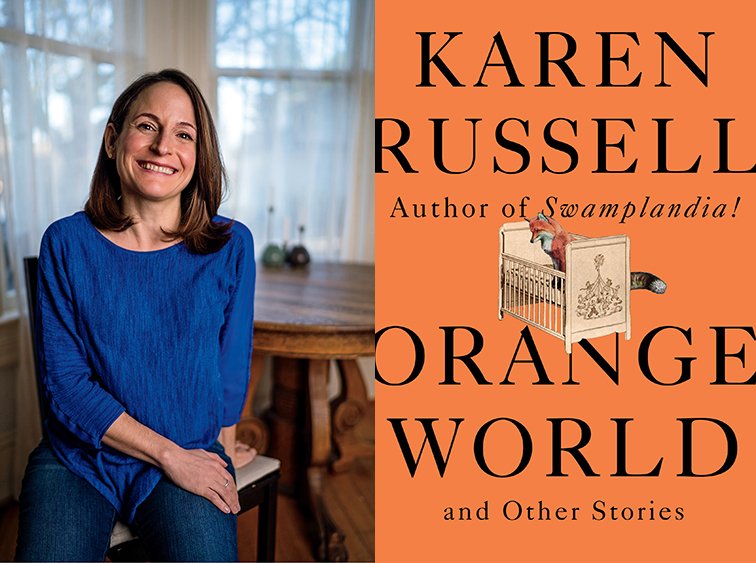

Karen Russell is a short story sorcerer. And with each collection, her powers grow. In Orange World, her third, out tomorrow from Knopf, she whisks the reader through time and space—from a snowy Oregon mountain lodge during the Great Depression to a future Florida flooded by an engorged sea. In one story the reader is swept off to a medieval village in Croatia plagued by corpses not content to rest in peace. As in all of her stories since her debut, St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves (Knopf, 2006), the real and the fantastical blend without seam. This literary alchemy starts with the core elements, her words—nouns are wielded as verbs—and builds fractal-like as the narrative progresses. Sentences that begin as simple declarations leap into the figurative, landing as poems. Historical fiction twists into speculative horror. A lover’s walk through the desert becomes a meditation on the borders between people and their environment. The supernatural morphs into a grand metaphor on motherhood. Nothing is as it seems to be.

As high as Russell’s imagination soars in the eight new pieces in Orange World, the characters keep one foot on the reader’s throat. Though it’s chilling to tour the drowned cities of post-climate Florida by gondola, the driver—a lonely mutant girl who navigates by echolocation and lives in a seaplane hangar with her three sisters—is the narrative lodestar. Such intricately drawn characters require space to run, and the stories in Orange World stretch long, bringing to mind the ambitious tales of Kelly Link and George Saunders.

I’ve had the pleasure of talking with Russell, who has also published a novel, Swamplandia! (Knopf, 2011) about her inventive work before, and over the course of a few weeks, as the weather shifted from brutally cold to delightfully warm and the air became laden with petals and pollen, we exchanged a series of e-mails about her new collection.

The title of each one of your books—St Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, Swamplandia!, Vampires in the Lemon Grove, and now Orange World—references a place. In this new collection, the story settings feel even more diverse than in your previous ones, and exquisitely described, and so integral to the tales that you tell. How does setting work in regard to your process?

When I’m writing, I nearly always begin with setting; characters come later, and I wouldn’t be able to imagine them if I didn’t have a sense of where they lived, or in some cases, how far from home they had traveled. I was just on a wonderful panel with Luís Alberto Urrea and Emily Fridlund and we discussed the fictional and real landscapes to which we keep returning: swamps, forests, borders. Luis said, “There’s place, the physical location. And then there are the stories you tell about that place.” I’m so interested in how the sight lines, soundscapes, flora and fauna of our childhoods shape us—how those earliest encounters with the land become part of our private, interior vocabularies of dream and thought. And I love novels and stories where geography shapes plot and gives rise to character. I think the question “What’s possible or impossible for this human personality in this landscape?” is a good starting place for fiction.

With short stories it feels possible to hop across time zones and zip into new skins; also to take risks that I think would prove unsustainable for the length of a novel. World-building is such a pleasure for me, as a writer and as a reader, and I love story collections because they feel like a miniature universe, with all these interrelated worlds-in-progress. Do you ever find yourself feeling that peculiar deja-vu as a traveler, as if a memory is returning to your body of some place you’ve never been, in this life? Or do you find yourself haunted by scenery that feels both remote from your lived experience and strangely familiar to you? I love that feeling and am always looking for it, in life and in books.

I thought of Orange World as being primarily a collection of long landscape stories, where setting is not a static, painted backdrop for human dramas but where nonhuman nature intersects with a character’s interior world. So, for example, a woman finds herself trying to navigate the surreal, slippery topography of new motherhood during an extreme Portland winter. Two honeymooners lose sight of their horizon in a literal desert. And I miss Florida every day, so there is a story here, “The Gondoliers,” set on the canals of a drowned South Florida in the floating future. It’s true that the landscapes in this collection are far flung, relative to my earlier collections, and I was happy to return to my home state, which really is the ur-landscape for me.

I hope that the human animals here feel like one element of a much larger story, because it’s that interaction between human and nonhuman nature that truly fascinates me; and the bad trouble people get into when they fail to respect their own and nature’s limits.

You’ve set one story, “The Bad Graft,” in Joshua Tree National Park. This struck me as unusual. It seems like you often pass a location through an imaginary filter, but Joshua Tree is a real place, and you situate the story within a geography that actually exists. How did this story come about?

I went to Joshua Tree National Park on my first date with my now-husband, and while this story is in no way autobiographical, I do associate the vastness of the desert with the vertiginous feeling of falling in love with him. I had never been to the desert before and never seen a Joshua tree; I felt like those Joshuas were only holding their poses, waiting until our backs were turned to wave into new shapes. The millions-year long co-evolution of the Joshua tree and the yucca moth is stranger and more beautiful than anything I could ever dream up, and I was grateful to find this living metaphor for a love-and-horror story about our interdependency.

Though “The Bad Graft” does feel slightly closer to contemporary consensus reality than some of the other stories, it also features a tree spirit possession. Maybe here the imaginary world is that overlapping Venn between Angie, Andy, and the Joshua tree, and the real desert was sufficiently mysterious to me that I didn’t need to make any fun-house mirror alterations to move out of my ordinary perspective into fiction.

One thing I love about all of the characters in this collection is that, like Angie and Andy in “The Bad Graft,” they’re not wealthy. They worry about money, and they work hard for it. The grifters in “The Prospectors,” Clara and Aubergine, for instance, are as much victims of societal oppression as the twenty-six impoverished men of the Oregon Civilian Conservation Corps who built the grand Emerald Lodge and then died in it when an avalanche swept the building away. On the surface, “The Prospectors” reads like a classic ghost tale, and yet at heart it strikes me as a political story. Do you think of yourself as an overtly political author? Or am I projecting too much?

I don’t think you’re projecting at all, although I rarely have a wholly conscious ambition for a story when I begin, beyond a wish to explore a certain collision of landscape and character and desire. I did have an inkling, when I began “The Prospectors,” that the catalyst for the story would be two young women who were prospectors, treating their future together like speculators, panning for golden horizon light somewhere far from home. And that we’d watch their early hope darken into a kind of desperation, and see how hunger, figurative and literal, can underwrite many forms of denial and delusion.

Shortly after I moved to Oregon I visited the Timberline Lodge on the side of Mt. Hood, “an architectural gem atop a natural wonder,” the showpiece of the Works Progress Administration (made famous by that ominous aerial shot that opens The Shining, to which this story certainly owes a debt). I was so moved by the black-and-white photos of the WPA and CCC crews, these bony young men trying to hoist themselves and the nation out of the Depression by building a fantasy ski resort. These boom and bust cycles in American history fascinate me; today, Oregon’s coastline is haunted by once-bustling ports and timber towns. The Columbia River bar is home to so many shipwrecks it’s known as “the graveyard of the Pacific.” I am always interested in the dreamers who navigate the shoals, who discover, often belatedly, that their dream is poorly suited to the reality in which they find themselves. The West is rich in stories of those dreamers who succeeded, but there are so many nameless others who got mowed under, and today we have a president who talks about “winners” and “losers” as if the entire onus for success or failure is on individuals, when in fact from birth onward the deck is stacked so profoundly against millions of people in our country.

I hope “The Prospectors” has contemporary resonance for readers, both insofar as it explores the way financial insecurity can transform interior and exterior landscapes, and because it looks at the way that women are often tasked with supporting an entire infrastructure in unacknowledged, uncompensated ways (in this story, Aubby and Clara do their “prospecting of the prospectors” by quite strategically propping up male egos and underwriting a ghostly world of male power and ambition, siphoning off wealth’s remainders, long before they are called upon to donate their life force to the phantom lodge and the ghosts inside it, minting them into reality). The precarity of the women’s position on the mountain, the careful way they maneuver through that party, is not so distant, I think, from the existential and economic calculations many women must make today in our tilted world.

Throughout the collection, these political and symbolic dimensions never compromise the narrative. By which I mean, your stories open themselves up to interpretation, they seem to invite it, and yet they’re always first and foremost gripping, expertly told tales. When writing, do you consider the figurative elements of the story, and what the reader might see in it? Or are you simply trying to tell the tale?

A friend of mine whose work I adore, Kevin Brockmeier, recently told me, when I asked him a question about his new book, “It’s as open to my discovery as it is to the reader’s.” I do feel that if a story is working at all, that has to be true; there has to be some mysterious and uncontrolled dimension to it that continues to offer itself up to interpretation. At the same time, I usually begin with at least a shadowy notion of what the story’s concerns might be; and then in the best-case scenario, a story eludes my initial ambitions for it and takes on a life of its own.

You’re a parent now, and I’m curious to know if that’s affected your work in any way, both practically—in terms of carving out time for writing—and creatively. We’ve bonded over our appreciation of Stephen King before, and I’m especially a fan of Pet Sematary, which explores the dark side of a father’s desire to keep his family intact; he literally violates the laws of nature, bringing his dead son back from the grave. Helen Phillips’s excellent forthcoming novel The Need covers similar terrain. The fantastical situations in these narratives shed light onto the shadows of parenting that realism can’t illuminate quite as effectively, I think. For me, your story “Orange World” exists on this same level.

I love Pet Sematary too, for the same reason, the deeply human wish at its core and the shadow side of the father’s love. I reread recently, and am still haunted by, Doris Lessing’s maternal horror story The Fifth Child. And I just started Helen Phillips’s The Need this very week, and it is wonderful. Her previous novel, The Beautiful Bureaucrat, was such a good friend to me when I was pregnant with my son.

My son has changed everything for me, in ways that I am still finding difficult to articulate without defaulting to cliché. I felt quite muted by the experience and I was very grateful when I began, slowly, to write fiction again. Perhaps half the stories in Orange World were written during my pregnancy and the early months of our life together; I turned the book in a couple months before his second birthday. I’m pregnant right now, with a daughter, due the first week of August, and I will tell you that the most notable way this has affected my work is by making me a much slower writer. But I also feel more like a writer, if that’s not too contradictory—a writer who is having a hard time finding her rhythm on paper at the moment, maybe, but I do think I’m paying a new kind of attention to this place.

I want to say here that I don’t want to give accidental support to the pernicious old story that motherhood is somehow a woman’s highest calling; innumerable stories of love and transformation are currently unfolding on our planet and this is one of many. But I do feel transformed, on a cellular level. Wrenched open, and riveted to my skin, and zipped into the present moment with my son in a way that reminds me strongly of my own early childhood, when one’s home was the size of the Universe and everything had a particularity and sheen and shadow to it—a unique life, because nothing had a precedent yet.

That might be my way of disclosing that a practical change is that I spend a lot of time at home with our son right now. So there’s the exigencies of diaper-changing and feeding and the repetitive fear that causes me to comb over our stairs for potential hazards, and this is not my favorite use of the imagination, whatever scenario-generator now compels me to view the bathtub and the playground and etc. as possible Lands of Present Hazards and Future Regrets. If you were to look at a day’s itinerary, it would seem happy and boring, and in no way revelatory of the intensely bright and also shadowy emotional landscape we are living. It also would fail to suggest the atmospheric pressures and shared global and local concerns of our surreal epoch, where so many lives impinge on our own thanks to new technologies, and yet the reality of others’ suffering often gets flattened into pixels on the screen. I remember looking down at my phone a few months ago to see, stacked in my push notifications, “Migrants tear-gassed on the border” and “Get the most out of Cyber Monday!”

I desperately need speculative fiction right now, as a writer and a reader, to open up an elastic space where it’s possible to represent all of the dimensions of love and of horror, the utopias and dystopias co-evolving on this planet. So if there’s something crazy happening—a huckster demon with a thirst for mother’s milk shows up, say—it’s in the service of a kind of extreme emotional realism. Or as Flannery O’Connor says, where “the truth is not distorted…. but rather a distortion is used to get at truth.”

Brian Gresko is a widely published writer and editor of the anthology When I First Held You: 22 Critically Acclaimed Writers Talk About the Triumphs, Challenges, and Transformative Experience of Fatherhood. He cohosts Pete’s Reading Series, the longest running literary series in Brooklyn, New York.