In late 2016, adoptee poet and Kundiman fellow Leah Silvieus initiated a research project about the ways in which emerging adoptee poets contend with identity, loss, culture, and family in their work. She sent a query through the Kundiman network, looking for Asian American adoptees who would be interested in participating, and the three of us—Tiana Nobile, Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello, and Ansley Moon—eagerly responded.

To be in community with not only fellow transracial, transnational, Asian American adoptees, but also poets was incredibly meaningful. We quickly realized that navigating the world as transracial, transnational adoptees and sharing a deep affinity with language in turn made our relationships with one another particularly affirming. This initial meeting led to us forming an adoptee book club. Marci had just read Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere (Penguin Press, 2017) and wanted to talk about the book’s adoption narrative. From there we read more books written by both adoptees and non-adoptees, all featuring prominent adoptee characters. We began to notice recurring tropes that reflected problematic understandings of the adoptee experience, including the white savior and the insistence on reunification as a solution to all problems. In reading, processing, and critiquing in conversation together, we have been able to develop a unique analysis of these narratives, grounded in our own adoptee experience. It is an analysis and perspective that we think is too often excluded from mainstream literary discourse.

In 2019 the three of us presented a panel at the New Orleans Poetry Festival about our book club and the significance of building community and finding kinship among fellow adoptees of color. Poet, friend, and Kundiman executive director Cathy Linh Che attended the conference and stayed with Tiana. The night after the panel, over crawfish and sangria, she asked if we had thought about starting a collective. At that point it hadn’t crossed our minds, though we were already functioning like one. Cathy insisted that we should, that our voices and stories mattered. Her encouragement was the push we needed to make it official.

Since that panel, we have continued to meet and support one another’s work. Most recently, in April 2021, we celebrated the publication of Tiana Nobile’s debut poetry collection, Cleave, at a reading hosted by Kundiman that featured a lineup of luminary adoptee writers, including Silvieus, Sun Yung Shin, and Matthew Salesses. Now we are thrilled to announce the launch of our adoptee and artist collective, the Starlings Collective, with a mission to honor the experiences and elevate the work of African, Latinx, Asian, Arab, and Native American (ALAANA) adoptee writers and artists through public events, workshops, and more. Adoption is a global phenomenon that is informed by the intersections of multiple systems of power, including white supremacy, sexism, ableism, war, and colonialism. Erasure and displacement are inherent in adoption stories, and there is no singular adoptee narrative. We aim to elevate and deepen the breadth of adoptee narratives. By interrogating the ways in which mainstream adoptee narratives reflect broader understandings of adoptee identity and shape policy, we consider the consequences such depictions have on social and political institutions.

We inhabit different corners of the world: Brooklyn, New York; New Orleans; and Miami. Over the course of the summer of 2021—with some help from Zoom and Google Docs—we met and discussed questions we posed to ourselves about writing, survival, and community.

Arrivals for adoptees are complicated. However you’d like to reply, how did you arrive?

Nobile: I arrived on a plane. I arrived in the arms of a stranger. I arrived when I was six months old mysteriously dressed in multiple layers of clothes, several onesies fitted to my tiny body. I arrived at JFK’s International Terminal in Queens, New York, via Seoul, via Daejeon, South Korea. Twenty-one years later, I arrived in New Orleans in a red 2005 Mazda Tribute. I arrived to this friendship after years of flailing, of searching for mooring without an anchor. I arrive to this conversation with an open heart and a belly full of gratitude.

Cancio-Bello: Tiana, your response makes me think of your poem “Revisionist History.” I arrived in the world long before I arrived in America. Though I do not know my own origin story, I did not begin in an airport, so I must constantly revise what I imagine my earliest arrivals to be. In this way I am always arriving. In some ways, too, I am perpetually departing.

Moon: I arrived as a question. A daughter departed. Armful of bangles and a white dress. I’ve been thinking about how the word arrive comes from the French word arriver, meaning to reach the end of a long journey. Like you, Marci, I am always arriving and departing. Writing, too, feels like a series of arrivals and departures.

In a March 2021 op-ed in Time, prolific writer and adoptee Nicole Chung wrote, “I lived every day from the age of 7, when I heard my first slur from a classmate, understanding that my Korean face made me hypervisible where we lived—and that it could also make me a target.” What is your earliest memory of race?

Nobile: Like Nicole, my earliest memories of experiencing racism took place at school. In first grade, a boy with hair so blond it was almost white and a face full of freckles ching-chonged at me over the bus seats. It was then that I realized people perceived my body differently than the rest of my family. I went home and told my mother, who told his mother, who made him apologize.

He was also very young, and I remember when he apologized, he had a confused look on his face. Now, having spent over a decade working with children, I doubt that he knew why what he said was harmful and was most likely parroting something he had heard directed at bodies that looked like mine. Also being six years old, I don’t think I knew why it hurt me, either; it just did. Regardless, he intuitively knew it was a way to hold something over me, to humiliate and assert power. For me, the moment imprinted, and my body began to harden.

That was my first overt experience with being racialized; however, in retrospect, there are earlier memories, like my family calling my likewise-adopted brother “Buddha boy.” When I learned the word microaggression in college, I realized I had been collecting them for years in my memory’s arsenal, without any space to release or process. I was a tightly wound ball of anxiety and self-loathing, which made me an easy target.

Moon: Tiana, your early experiences resonate so deeply with me, as does your comment about holding and processing these racist encounters solo. I’m so sorry that this happened, and I wish that I could have been on that bus with you.

In many ways I find this question the hardest to answer because growing up, in my adoptive family, I was the only nonwhite person. It was a lonely place, especially because I felt so profoundly different, and no one else in my family experienced the world like I did.

When we moved from a suburb of Atlanta to the North Georgia area, I remember how being different turned dangerous. I went from being around other nonwhite children to being one of only a few nonwhite people around. Small children would gape and point at my brown body. Strangers would stop and interrogate me: “What are you?” A white boy told me I smelled because I was brown and dirty; meanwhile, his friend would drag his finger slowly across his throat and laugh each time he saw me.

One day, when my family and I were out grocery shopping, we saw the KKK march in our town. My mother was forced to pull over, and she quickly instructed me to hide in the back seat. My body, it seemed, was always a target, always in jeopardy. Another time I recall being tied to a pole and abandoned by three white boys who I thought were my friends. As the bell rang, several classes let out to find me screaming. I remember a white teacher telling me it was my fault. What saddens me most about these experiences is that I navigated them alone because I did not know how to share them with my family.

Cancio-Bello: Ansley and Tiana, I’m so sorry you had to go through these horrible experiences alone. I wish I could have been there with you both. I don’t remember a time when I was not hyperaware of being racialized, though I grew up extremely isolated. As homeschooled kids in an Appalachian hamlet, my brother and I were the only nonwhite people for miles. We did not even interact with other children our age, except in monthly church gatherings, though I remember being locked in a church nursery by some older girls who told me to wait until my “real parents” came back for their “Asian princess.”

My adoptive parents were obsessed with Asian culture and often spoke of me and to me in the language of commodity. In my earliest memories my adoptive mother exoticized my “china doll lips” to strangers who asked “what” I was. They told me several times that they had wanted to adopt from China, but by the time they had saved enough money, it was much easier to get babies from South Korea. In a house where being noticed was dangerous, I always felt like a target to my own adoptive parents. I don’t think their racialization was conscious, but when in recent years I’ve tried to have conversations about race with them, they said it hadn’t occured to them that I might have experienced racism and were not interested in talking about it.

As adoptees it might be useful to separate racism from loved ones and racism from strangers. They are different forms of pain in which a racialized experience is compounded by the ignorance and indifference of loved ones who look like the initial perpetrators. For example, in the early months of the pandemic, friends and family spoke incredulously about the violent hate crimes against Asian Americans, only to be surprised that I didn’t leave the house for four months. I was not, in their minds, Asian—or at least Asian enough—to be in danger. This makes me wonder what your experiences with racial violence have been as adults, both before and then during the pandemic.

Moon: Marci, I appreciate this question. I, too, have had similar conversations with family members when I asserted that they see me as a queer South Asian person. Why is it that others are so threatened by our bodies, our existence? Violence against my body isn’t new. I am reminded how radical it is to write, to exist.

To answer the last part of your question, I feel very fortunate that I was able to work remotely for most of the pandemic. However, as the world pushes to “reopen,” what can we do to keep each other safe?

Nobile: Ansley, it makes me so sad to hear about your early experiences growing up in North Georgia. That your body was ever treated with anything less than care infuriates me, and I, too, wish I had been there for you on the playground. My experiences with violence have often been tied to the sexual objectification of my body. I’ve had my vagina grabbed while walking down the street. Another time, a group of teenage boys yelled “Chinese pussy!” out of their car windows before cackling and speeding off. I have so many stories like this. My experience with the exoticization of the Asian body preceded my knowing there was a word for it. During the pandemic I didn’t expect to feel so comforted by the quiet safety of being tucked in my home. I’m incredibly fortunate to have been able to stay home during such a tumultuous time, but your question, Marci, makes me think about what else we might need to seek refuge from, particularly with the rise in anti-Asian violence over the last year and a half.

As an adoptee, what does it mean to survive? To write?

Cancio-Bello: Tiana, your book actually addresses a lot of what it means for adoptees to survive in many versions of that word. Speaking of microaggressions from loved ones, so much is revealed in the title and first line of your poem “Did you know”: “my sister was Fed-Exed from Korea?” Personal documentation shifts in the second part to adoptees in the news. How many people know of the Vietnamese babies lost in 1975 when the first plane crashed in “Operation Babylift,” as described so heartbreakingly in your poem of the same name? And your poem “The Last Straw” guts me every time, with its epigraph: “U.S. woman put adopted Russian son on one-way flight alone back to homeland. —NY Post headline, 9 April 2010.” I read an early version of your manuscript around the time news circulated of YouTube celebs Myka and James Stauffer “rehoming” their adopted son, Huxley, and I wondered if, given another year or two, what other poems you might have written and added to Cleave.

While many of us have survived into adulthood in the most literal sense, I wonder how much of ourselves has survived intact along the way. Adoptee activists have pointed out how similar the adoption industry is to human trafficking. Children are still being bought, kidnapped, or tricked from their families. Adult adoptees have been deported because their adoptive families did not or would not finalize their naturalization paperwork. There is still somehow opposition to the Child Citizenship Act of 2000 and the Adoptee Citizenship Acts of 2019 and 2021. We are too often expected to feel “grateful” (read also: subservient, controllable) for being told we are secondhand and second-choice. It is no wonder adoptees are four times more likely to commit suicide than non-adoptees.

What then can survival really look like for adoptees? My poet-sister E. J. Koh has a stunning essay in Catapult in which she says, “If there was value in any life on earth, then value must be present in mine. If I believed in this one thing, I could write freely. I learned to know my life as valuable.” Anger helped me to survive. Writing has taught me how to love and see my life as valuable.

In his revolutionary book Craft in the Real World, fellow adoptee Matthew Salesses speaks of writing as power. He writes, “What we call craft is in fact nothing more or less than a set of expectations. … How we engage with craft expectations is what we can control as writers. … These expectations are never neutral.” These days I contemplate how writing is both resistance and reclamation. There are so many stories America has tried to hide from us, our own included, but we cannot be stopped from finding them, or from telling our own. How else do we survive, except through stories?

Nobile: Marci, I think you make such an important point about the difference between surviving and thriving. Sure, many of us are technically still here, but how do we account for what was lost along the way? I carry so much rage because of the circumstances that brought me here, more precisely the long history of American occupation and military intervention that resulted in the destabilization of innumerable countries, many of which continue to suffer to this day. People like to consider South Korea a success story, but this telling entirely erases the separation of countless families when the DMZ line was drawn; it erases the lives that were lost as a result of the American war machine; it erases the hundreds of thousands of children who have since been taken away and adopted and their biological families who also suffered the consequences.

I write because I must. Because it’s the only way I know how to make sense of my rage and grief. Because I spent the first half of my life in silence, afraid of the sound of my own voice. Because I won’t be silent anymore. Because writing is a road toward healing. Because we deserve to heal and thrive.

Moon: I love both of your answers here.

Each day I am still learning what it means to survive, what it means to live in a body ravaged by illness. When I first came to the United States, I was so sick the doctors thought I would not live to see my second birthday. I am hurtling toward death, but for now I am still alive. I write because I was never meant to survive. I write because my adoption was a form of disappearance—and yet here I am. I write because, as Audre Lorde wrote, “…there are so many silences to be broken.”

What might you want to say about adoptee representation in media?

Nobile: Time and time again we see adoptees inserted into narratives in ways that deny us a full and complex expression of self. So often characters are made into adoptees because it’s seen as an easy way to increase diversity and seem inclusive, and yet they ignore the ramifications of such a specific choice. I’m thinking of the A Wrinkle in Time movie that came out a few years ago. In the movie’s climax, the dad prioritizes saving his biological daughter and abandons his adopted son. Though the daughter ultimately returns to rescue her brother, the family never reckons with this choice and its consequences. Adopted kids have so few positive visible representations of themselves in film, TV, media, and literature, and this scene reinforces many adoptees’ deep fear of expendability. I’m also thinking of the new Netflix show The Chair. Of course, [the adopted character] Ju Ju is very cute, but her behavior is disregarded, and her antics are seen as comic relief. Matthew Salesses recently tweeted, “Characters are always going to be taking into account and [sic] race and gender because they’re a part of every interaction, but adoption isn’t. You can’t just add an adopted character without actually engaging with the ethics of adoption.” Making a character an adoptee completely shifts their position, and this needs to be considered when including adopted characters. We are not your token BIPOC.

Cancio-Bello: Absolutely! Tiana, you said it so beautifully, that we are denied “a full and complex expression of self.” Adoption often seems like an “easy” way to give a character a traumatic backstory or explain negative behavior. Consider the differences between Superman’s and Loki’s backstories. The Chair resonated with a lot of people familiar with academia, and I love Sandra Oh, but I wonder what are the implications of Ju Ju’s first mother being Mexican, or that Bill, the white cis male love interest, is the only one who connects with Ju Ju, over a Mexican tradition, no less. While stories about blended families often include a character saying, “I would never want to replace your [parent],” the expectation is that adoptees’ first parents are utterly expendable (and unqualified) and that adoptees should be blank slates who accept parental swap-outs without a fuss. I do not mean that all adoptees are unhappy with their adoptive families, or that finding one’s first parents is unimportant, but these cannot be the only narratives we see. It was considered a huge breakthrough when Modern Family introduced Lily, a Vietnamese baby adopted by Mitchell and Cameron, and it remains one of the few inclusive LGBTQIA+ story lines I’ve seen, but even then the nuances aren’t always addressed. Adoption is complicated for all parties involved, and very few representations understand all the ethical complexities of including such narratives. Add transnational, transracial adoption into the mix and it gets even harder. This is why there cannot and should not be one representative narrative. Adoptees are not a monolith. We do not all come from the same places, we do not have the same histories and personalities, we do not want the same things in life—except perhaps to see ourselves.

Moon: Yes, Tiana and Marci!

What Asian American poets and/or adoptee poets have affected your writing?

Cancio-Bello: I do not have the privilege of going home to people who look like me. I have had to conscientiously educate myself on what it means to move through the world as an Asian American woman, to reclaim access to lullabies and histories of people who look like me. I have spent my whole life seeing terrible representations of adoptees and orphans in mainstream media and being told we are undesirable. I think of the first Asian American poets I read—Li-Young Lee and Aimee Nezhukumatathil—and how they astonished me and opened doors of possibility. This is how I began to love my Asian-ness.

I remember Marilyn Chin, at my first Kundiman retreat, encouraging me to write about adoption (or else she would haunt me forever, she said); Lee Herrick, one of the first to recognize me as a fellow adoptee; Sun Yung Shin telling me she could count on one hand the number of AAPI adoptee poets in her generation; Jennifer Kwon Dobbs hugging me after a reading and calling me sister; Nicole Chung’s memoir, All You Can Ever Know, gaining attention worldwide. Reading Don Mee Choi’s poems and translations felt like I’d found home for the first time, and I treasure her friendship fiercely. Leah Silvieus’s Arabilis; Ansley, your book, How to Bury the Dead; and Tiana, your book, Cleave, each speak to the adoptee experience in different ways I’d never seen represented before and that resonate deep within me. I am also seeing a new wave of high school and college adoptee writers beginning to rise. It seems that wherever I go, we find each other. This is a beautiful community that I never knew existed, and yet see how we rise together.

Nobile: In the 1980s and 1990s, white parents adopting children of color were told that color-blind assimilation was the best way to integrate us into the family. While I like to think that this decision was not made maliciously, it ultimately denied us the exploration and expression of a huge part of our identities. My family had no idea what it meant to be a Korean kid growing up in a predominantly white Long Island suburb, and I had no support system in place to help me figure it out. Like you, Marci, I’ve had to learn how to navigate the world as an Asian American woman without guidance or a road map.

I remember discovering Sun Yung Shin’s Skirt Full of Black when I was in my early twenties. I had never met a Korean American adult adoptee and couldn’t even fathom one who also wrote poetry. I never could have imagined that years later, I would call Sun Yung a dear friend. Later I found Lee Herrick, Jennifer Kwon Dobbs, Nicole Chung, Matthew Salesses—all brilliant writers who are doing such important work to center adoptees’ voices and perspectives and shift prevailing notions around adoption. For too long, adoptive families and agencies have engineered and controlled the narrative, which is often grounded in religious savior complexes. By not being the tellers of our own stories, our existences become flattened and our bodies objectified. Adoptee writers are deepening and expanding understandings of the adoptee experience, which is complex and specific and far from a monolith. For me it’s profoundly special to see glimmers of my own experience in other people’s work. It’s a tacit understanding and closeness that isn’t replicable. I feel this most deeply when I read work by other transracial adoptees and by being in conversation and community with our collective.

Moon: As both of you experienced, representation was limited for me growing up. I longed for a mirror. I longed to see someone who resembled me in some way. I wish that I could have had your books, Tiana and Marci, growing up. Two adoptee writers who I first encountered were Sun Yung Shin and Jane Jeong Trenka. Saroo Brierley’s book A Long Way Home was one of the few South Asian adoptee narratives I read, and the intense longing and sadness gutted me. I began making a list of Asian American writers I deeply admire, but the list got too long!

What has been inspiring you lately? Or what’s a poem or piece of writing you keep returning to, and why?

Moon: I have been especially into reading memoirs lately. I love nonfiction and the way that my favorite nonfiction writing echoes poetry and haunts. Akwaeke Emezi’s Dear Senthuran took my breath away. I also loved Antiman by Rajiv Mohabir and Fairest by Meredith Talusan. I was excited to participate in the Sealey Challenge, poet Nicole Sealey’s invitation to read a book of poetry a day for the month of August. On deck this month are Sahar Muradi’s Ask Hafiz; Guillotine by Eduardo C. Corral; Muriel Leung’s Imagine Us, the Swarm; Borderland Apocrypha by Anthony Cody; and Upend by Claire Meuschke.

Nobile: At a time when the pandemic is far from over, and I feel my world beginning to close back in again, I’ve been reconvening with old friends in other ways. Matthew Olzmann’s poem in the New York Times, “Letter to a Bridge Made of Rope,” was a welcome salve amid rising COVID numbers and subsequent anxiety. I’m rereading Macnolia by A. Van Jordan and remembering the deep breadth of it and continue to be impressed by how much a poet can accomplish in a single book. I also just reread Chen Chen’s When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities as a reminder and lesson to myself on how to imbue humor and tender vulnerability in my work. I’m honored to have my shelves (and browser!) filled with my friends’ words—poems I can turn to for inspiration and solace and to feel a little less lonely.

Cancio-Bello: I have been spending a lot of time with Joy Harjo’s poem “For Calling the Spirit Back From Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet,” which starts with “Put down that bag of potato chips” and ends with “Then, you must do this: help the next person find their way through the dark.” Rather than expecting others to make conditions right and hold open doors for us, we can open them ourselves, call our spirits home, and invite others to step through with us.

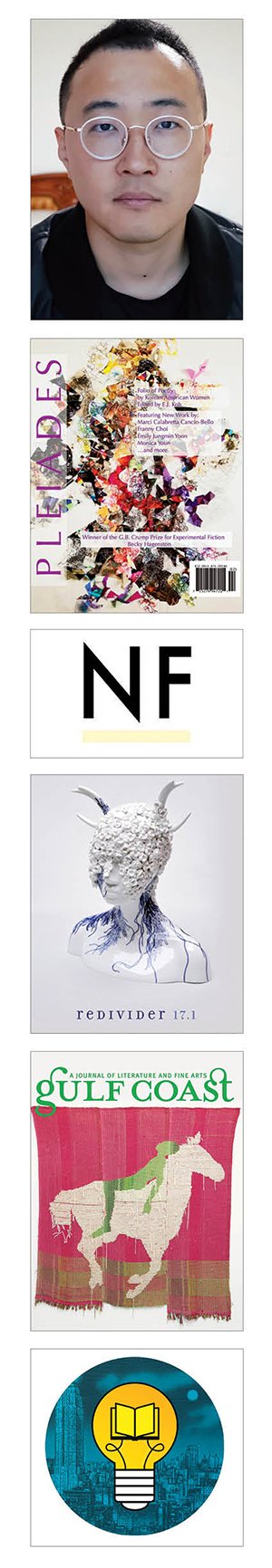

Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello is the author of Hour of the Ox (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016), which won the Donald Hall Prize, and co-translator of The World’s Lightest Motorcycle (Zephyr Press, 2021) by Korean poet Yi Won. She has received fellowships from Kundiman, the Knight Foundation, and the American Literary Translators Association. Her work has appeared in Kenyon Review Online, Orion, the New York Times, and elsewhere. She serves as a program coordinator for the Miami Book Fair. Her website is marcicalabretta.com.

Ansley Moon is the author of the poetry collection How to Bury the Dead (Black Coffee Press, 2011). Moon is the recipient of fellowships and awards from the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, Kundiman, and the Mae Fellowship and is currently working on a second poetry collection, Register the Missing, which has been a finalist for the Pleiades Press Editors Prize and the Slope Editions Book Prize. Moon’s website is ansleymoon.com.

Tiana Nobile is the author of Cleave (Hub City Press, 2021). She is a Korean American adoptee, Kundiman fellow, and recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award. Nobile was a finalist for the National Poetry Series and Kundiman Poetry Prize, and her writing has appeared in Poetry Northwest, the New Republic, Guernica, and Southern Cultures, and elsewhere. She lives in Bulbancha, also known as New Orleans. Her website is tiananobile.com.

Based in Los Angeles and funded by PEN Center USA, the press publishes twelve books of translated poetry and fiction each year, and also produces literary films—video poems, paratextual films, and short documentaries—that feature the press’s authors and translators. A look at just two months’ worth of Phoneme titles is a trip across several continents: In December the press released Smooth-Talking Dog, a poetry collection by Mexican writer Roberto Castillo Udiarte—also known as “the Godfather of Tijuana’s counterculture”—translated from the Spanish by Anthony Seidman. Richard Ali A Mutu’s novel Mr. Fix-It, translated from the Lingala language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Bienvenu Sene Mongaba and Sara Sene, was also released in December. This month the press publishes its first Icelandic translation, Cold Moons by Magnús Sigursson, translated by Meg Matich; as well as The Conspiracy, a thriller by exiled Venezuelan novelist Israel Centeno, translated from the Spanish by Guillermo Parra. The Conspiracy is the second book in Phoneme’s City of Asylum series, which features works by exiled writers receiving sanctuary in the United States. Phoneme’s general submissions are open year-round, and can be sent via e-mail to

Based in Los Angeles and funded by PEN Center USA, the press publishes twelve books of translated poetry and fiction each year, and also produces literary films—video poems, paratextual films, and short documentaries—that feature the press’s authors and translators. A look at just two months’ worth of Phoneme titles is a trip across several continents: In December the press released Smooth-Talking Dog, a poetry collection by Mexican writer Roberto Castillo Udiarte—also known as “the Godfather of Tijuana’s counterculture”—translated from the Spanish by Anthony Seidman. Richard Ali A Mutu’s novel Mr. Fix-It, translated from the Lingala language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Bienvenu Sene Mongaba and Sara Sene, was also released in December. This month the press publishes its first Icelandic translation, Cold Moons by Magnús Sigursson, translated by Meg Matich; as well as The Conspiracy, a thriller by exiled Venezuelan novelist Israel Centeno, translated from the Spanish by Guillermo Parra. The Conspiracy is the second book in Phoneme’s City of Asylum series, which features works by exiled writers receiving sanctuary in the United States. Phoneme’s general submissions are open year-round, and can be sent via e-mail to

When I find journals that run essays containing bad behavior, deep reflection, and curse words, I send to them,” says Aaron Gilbreath, who published nearly every essay in his debut collection,

When I find journals that run essays containing bad behavior, deep reflection, and curse words, I send to them,” says Aaron Gilbreath, who published nearly every essay in his debut collection,  “Lit mags feel like old-school garage bands to me. When they aren’t tethered to commerce or some sales team’s expectations, they can focus on delivering highly charged, less commercial creations to a dedicated audience,” says Gilbreath, who seems to have found this in the New Orleans–based print biannual Bayou (

“Lit mags feel like old-school garage bands to me. When they aren’t tethered to commerce or some sales team’s expectations, they can focus on delivering highly charged, less commercial creations to a dedicated audience,” says Gilbreath, who seems to have found this in the New Orleans–based print biannual Bayou (

The closing essay of Gilbreath’s collection, “(Be)Coming Clean,” first appeared in the Louisville Review (

The closing essay of Gilbreath’s collection, “(Be)Coming Clean,” first appeared in the Louisville Review ( “When I wrote an essay about sleeping in my car and stealing hotel breakfasts in order to see bands play on a limited budget, and questioning my parental potential,” says Gilbreath, “the Smart Set immediately came to mind.” The Smart Set (

“When I wrote an essay about sleeping in my car and stealing hotel breakfasts in order to see bands play on a limited budget, and questioning my parental potential,” says Gilbreath, “the Smart Set immediately came to mind.” The Smart Set ( According to its editors, the print annual Hotel Amerika (

According to its editors, the print annual Hotel Amerika (