“Write something universal as illustrated by a deeply personal tale.” This advice is true regardless of the genre we write, and in this interview, Marion Roach Smith explains how we can dig deep into our truth and experience to write memoir, plus how she has created a business around a book, and a podcast around curiosity.

In the introduction, I talk about how the pandemic impacts our energy levels and how online business is changing, and how that might impact us as authors. Business Insider reports that Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Google’s Sundar Pichai, Apple’s Tim Cook, and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos will all testify before Congress in an antitrust hearing in late July. What are the potential impacts for authors?

Publisher Rocket now has a useful feature for discovering categories for your books. Dave Chesson talks about the new functionality and more on the Writers Ink Podcast last week.

Plus, join me and Nick Stephenson for a webinar on how to grow your book sales to $1000 a month — or add to your existing sales. We’ll be going through how to build your email list and convert that traffic into sales, plus tips for revisiting the basics of your author platform + some more advanced tips for taking sales to the next level. Thurs 16 July at 3 pm US Eastern / 8 pm UK. Click here to register for your free place and also receive the replay if you can’t join us live.

Today’s show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, where you can get free ebook formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Get your free Author Marketing Guide at www.draft2digital.com/penn

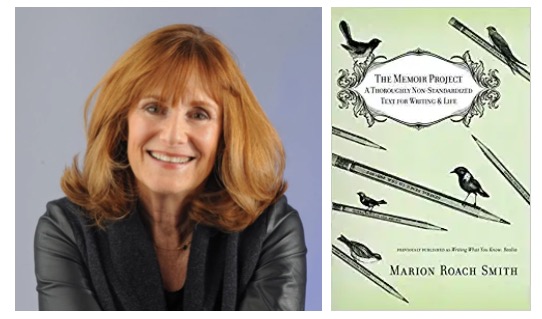

Marion Roach Smith is an author, memoir coach, and teacher of memoir writing. She has online courses on writing memoir. Her books include The Memoir Project: A Thoroughly Non-Standardized Text for Writing & Life.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and full transcript below.

Show Notes

- The difference between memoir and autobiography

- Why memoir is an argument-driven genre

- Where to draw the line between therapy and memoir

- Tips for skillfully writing about other people

- How memory works in memoir

- What does research look like for memoir?

- How to we ensure people care about our memoir?

- Being brave when marketing books

- Why podcasting is so powerful

You can find Marion Roach Smith at MarionRoach.com and on Twitter @mroachsmith. You can check out her QWERTY Podcast on your favorite podcast app.

Transcript of Interview with Marion Roach Smith

Joanna: Marion Roach Smith is an author, memoir coach, and teacher of memoir writing. She has online courses on writing memoir. And her books include The Memoir Project: A Thoroughly Non-Standardized Text for Writing & Life. Welcome, Marion.

Marion: Lovely to be back. It’s so great to hear your voice.

Joanna: You were on the show years ago (2013) and we thought it was about time that you came back on.

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing.

Marion: I’ve been a full-time writer since 1983 when I left ‘The New York Times.’ I had been there for six years and during that time I wrote a magazine piece for ‘The New York Times’ magazine. Arguably, certainly some people think the most powerful magazine in the world.

I had no idea how powerful until I wrote a piece for them at 26 that was really the first, first-person account of Alzheimer’s disease. Strangely enough, there was a time when none of us had heard of it and it launched my career, got me a book offer. And I left ‘The New York Times’ and have since published four books and lots of magazine pieces and done lots of radio work and op-eds.

And then started this thing called The Memoir Project a bunch of years ago that’s now online, which is a writing lab where I teach a lot of courses and there’s a book that goes with it called The Memoir Project. So I built a business around a book that I published, which is a model that I find interesting and I hope other people will find as well. I published this book in 2011 and then I built this online teaching business about memoir.

Joanna: Which is fantastic. And we’re going to come back to the business model in a bit because really great that you mentioned that. But let’s talk about memoir first.

How do you define memoir and how is it different from autobiography?

Marion: It’s a really important distinction. If you’re someone who’s really famous in this world, who’s the most famous person we can think of? We think of you, whoever your favorite rock star is, or whoever your favorite politician is, and we know where they end up, right?

We know what they do in the large sense, we’re going to be happy to read their autobiography because we want to know about the little decisions, we want to know about the college that they went to and who they dated. If it’s a rock star, we want to know who they had an affair with and where they went and where they go on summer vacation.

That’s autobiography, one big book that covers everything about your life.

For the rest of us, there’s memoir, which is written from one of your many areas of expertise and you have a dozen or so areas of expertise and is written in which you show us what you know after something you’ve been through. So you have a dozen areas of expertise, maybe you’ve had dogs all your life, maybe you did caregiving for a sick relative, maybe you’ve been in a long marriage, those are three different areas of expertise.

And for a memoir, you can have a writing life if you write from one area of your expertise at a time and don’t tend toward autobiography. So I keep it really simple.

Memoir is about one aspect of your life and autobiography is that big book that covers all aspects of your life and is best left to the famous.

Joanna: And best left until you’re dead or I guess it’s not autobiography now, but a lot of people do that later on, don’t they? They will let you say, I don’t know, Bill Clinton from nowhere to president and on after that type of thing.

Marion: Right. Although only you could write a book that is written by someone who’s dead. So I’m going to leave that to your fabulous genre. And I think you should make note of that, the memoir from the dead would be a fabulous title and I give that to you as a gift today!

Joanna: Thank you so much and anyone else listening. No, you’re completely right.

It’s interesting because you said there are areas of expertise which it’s a great phrase but it’s interesting because I think of area of expertise. I have books for authors as do you, obviously, but I would never think of writing a memoir about my time self-publishing.

So I wondered what are some of the ways to shape a memoir? You mentioned dogs, for example, there’s theme, and time, and place, but I think area of expertise could be so many things.

What are the ways that make it easier to grasp on to the things that people might care about?

Marion: So you’re going to be willing to argue something and I don’t mean argue, like get into a tussle, I mean propose something to us, something that you know after something you’ve been through. And you could in fact write a memoir from the calamitous, hilarious, and ultimately successful place of self-publishing.

Because I know from mass-market publishing, having published a book when I was 27 with one of the largest publishing houses in the world, I had a wild time in the true sense of the word out there on the road when they used to send authors out for two weeks and I could certainly have written a hilarious memoir from being on the road promoting a book.

So you could with enough of a sense of humor and real skill combine a how to end a fun memoir that’s written from that area of expertise.

But what I really mean is that you’re arguing something, this is how you start memoir. You answer the question, what is this about? And you think about the universal, not about your plotline.

That’s what you’ve been saying to people for years when they ask you, ‘What’s your book about?’ You’ve been telling them your plotline and notice how their eyes glaze over immediately. Instead, if you say it’s about the complicated journey of mercy, ‘Oh, you have my attention.’

And then you say, ‘As illustrated by my forgiving the man who abused me when I was a child to be told in a book.’

Look at the way that draws us in, it’s about something universal as illustrated by a deeply personal tale to be told in a certain length. And that universal, that first part of that sentence, I call it the X factor, is what you’re willing to argue that mercy is a complicated process.

So all you’re doing when you write memoir is drilling into the various things you have some expertise in. It might be mercy, it might be the fact that gardening brings peace to your soul, it might be that dogs do things for people that people cannot do for themselves.

I always ask people to consider each memoir from that area of expertise but that area of expertise is something you would be willing to share with us based on what you know, what you’re willing to argue. So it’s always, always, always argument-driven and not plot-driven.

Everyone makes the mistake of thinking memoir is a plot-driven genre, it’s an argument-driven genre, it’s about experience.

Joanna: Actually and that comes back to you, the difference to autobiography, right? Because autobiography is this happened, then this happened, then this happened and it is a plot in order whereas a memoir doesn’t have to be in order, does it?

Marion: No.

Joanna: It doesn’t have to be this week this happened, the following week this happened.

Marion: Exactly, quite the opposite because think of some of the things that happened to you that you did not understand until you were X years old. That doesn’t make a lot of sense if you’re writing about gardening but it does make a lot of sense if I get back to one of the examples I used a moment ago about an abusive experience.

Children don’t have language for what’s happening, but in therapy or with age or watching movies or reading good literature or whatever gives us that language to understand what happened to us also gives us the understanding to change the end of that story, to get control of it.

I’m not saying you deny it, I’m saying you get control. And once, as you know, you get control of a story, you can drive it where it needs to go, you can figure out where it ends.

So yes, I think autobiography is absolutely plot-driven and memoir can be told out of order, can be told in flashbacks, can be told in what enlists, if that’s your thing. It’s a wonderful genre but it’s wonderfully misunderstood by people and confused with autobiography all the time.

Joanna: You’ve mentioned deeply personal things and something you know based on something you’ve been through, which I really like that phrase. Now we all need therapy at some point in our lives.

Marion: Yes, yes, yes.

Joanna: But I feel that some people consider writing a memoir to be therapy.

Where are the lines between therapy and memoir? What can potentially go wrong if you get that line wrong?

Marion: The great smudge, as I call it. One of my favorite words, smudge because it sounds like what it is, doesn’t it? It’s like smudge. When you smudge that you get into trouble.

Writing memoir is the single greatest portal to self-discovery, that’s true. Because think of it. You say things like, ‘I really love my husband, he’s so great, he’s great, I mean like he’s great.’

Now what did anyone learn? Nothing. But if you tell me a story about your husband taking the time, 10 minutes or so to give you some really bad news by giving it to you in tiny morsels so you could metabolize it and the kindness that he showed when he did that, we’ll understand why you’re with that person for the rest of your life.

In other words, once you write that story, you start to feel something much more deep and abiding about that person about whom you’re writing. So that’s therapeutic, it absolutely is therapeutic but it’s not therapy.

In other words, I always advise people if they’re dealing with a tough subject to be in professional hands, psychiatric or psychological hands, or social work hands as well. But we don’t want to just blah-blah-blah all over the page and tell me how you got better. Nobody wants to read the sentence, I’m sober, I found God, I’m good. That’s not where we’re reading for.

We’re reading to fill our own sense of wonder or mercy or forgiveness and so if you just do therapy on the page, we’re not going to experience the transcendence that memoir is famous for. If the memoir writing is therapeutic for you, how great.

In fact, I think it always is because I think a deeper understanding of everything, even the relationship you have with your garden is a good thing.

Joanna: It’s interesting. I keep walking up to the idea of a memoir and then walking away again. And I have talked to people who say I spent 30 years writing this memoir, as in they did exactly that, approached it, and then walked away again and maybe wrote something and then walked away again.

Obviously how you teach it as well and how you said at the beginning you can have different memoirs, but can memoir be the one book that you write at some point that deals with that big thing in your life that you haven’t really talked about?

I feel like it can be a really big genre, but the way that you talk about it, it could also be, like you say, some stories about your garden.

Marion: It can be both. It could be a huge piece of work and then you could write five or six other book-length memoirs to take on smaller topics.

My education in this came by reading the great writer, Caroline Knapp who wrote my favorite book of memoir because its structure is perfect. It’s called Drinking: A Love Story. Also, my favorite title of any memoir and the only memoir I put in anyone’s hands when they ask for a suggestion of a book to read.

You may not like the story, you may not be interested in women in alcoholism, you may not like her voice, you may not like her, or whatever. But what she taught me when I read that book was she wrote from one area of her expertise at a time.

And then she wrote a book about the relationship she had with her dogs. And I thought, ‘Huh, what? Two memoirs? She’s under 50. What? I don’t get it.’ And then I got it, the penny dropped.

When she died, tragically young, her best friend wrote a memoir about their friendship. And so I think you can wait and write one book about something that has been really profound in your life, your relationship with God, your sense of forgiveness, of the historic violence that hurdled through five or six known generations in your family that you refuse to engage in or you can write one big one and five little ones or five small ones.

It’s giving permission to people to have a writing life and not just live in this one big book that begins with their great, great, great, great grandfather and ends with what they had for lunch today that I’m really committed to. I’m really committed to giving people a writing life and not one book that they never finish and no one ever reads.

Joanna: I kind of feel the same about fiction. I think that sometimes people think they should write just the one great American novel or the one great Pulitzer prize-winning novel and that’s actually a really hard aim for it. If you say, well, ‘I’m just going to write a story and then I’ll write another story and then another one,’ you’re far more likely to get somewhere if you do that.

So I quite like what you’re saying, but I do want to ask about writing about other people because like you’ve mentioned, there are some, let’s say using family abuse. It’s a regular topic but it’s an awful topic.

But we also know that people have different views on what had happened in the family history and if people are alive or people who love those people who are alive and there are a lot of potential legal issues but also emotional issues if you offend or upset other people in your family who you love.

What are your tips for writing about other people?

Marion: First write it. Let’s see what you have before you talk yourself out of writing it.

This is a good rule to follow because there are so many reasons not to write. You’ve been told it has no value, you’ve been told it won’t make you money, you’ve been told that you’re not good, you’ve been told you’re not good enough. We’ve all got that whole stew in our heads.

So let’s just start by not adding to that and saying, ‘Okay, I’m going to write it down and I’m going to use the real names. And here’s the key, I’m not going to show it to anyone and I’m not going to talk to my family about what I’m writing. I’m going to find someone who is invested in my success as a writer,’ that’s going to be a coach or maybe you have a friend who’s an editor, maybe you have a friend who’s a great reader.

My friends are mostly writers, I’m sure most of your friends at this stage in your career are mostly writers, so there are people with whom I can trade that time. And so you got to find somebody who’s invested in your success and who’s going to read well because we want to leave the names in this first draft.

We want to see what we really do have. Ninety-nine percent of the time people who set off to write a book of revenge stop doing so within the first 25 pages because there’s not much to say if all your intent is to just, ‘I’m going to tell my side, I’m going to set that record straight.’ It’ll wear you out or you’ll realize what a fruitless effort it is, so that will straighten itself out.

And then suddenly you might, like many of the people that I’ve dealt with and I’ve now worked with hundreds of writers who have written for me too, you might discover that what got taken from you as a child was not just the physical sense of safety but your voice as you got told don’t tell or you got told you like it or you got told, I’ll kill you if you tell someone and that your book ends up being about voice.

In other words, you may find out, I’m not saying you make it a different a better story, a more tolerable story, but if you write it, you may find that you’re arguing something that is far more universal, instructive, illustrative, therapeutic, positive and for you, I’m not saying it has to be a happy ending, then a book that recounts the abuse.

So we may be getting into very, very much lesser territory in terms of the legal aspects. However, there will be legal aspects, there will be emotional aspects, there will be family aspects. Memoir has consequences but we don’t know what they are until you write that first draft.

So first, I always tell people to write it, not share it with anybody and get someone who’s invested in your success. Yes, you may offend or upset people, the strangest thing is that you will almost always offend or upset someone because memoir is the hardest genre there is to edit.

In other words, you’re going to leave out second-grade teachers, dogs you’ve had, cousins, you might leave out siblings, you may never mention your parents in this book. So you are going to offend somebody anyway and that’s just true because you’re not writing a big book with everybody in it.

Let’s first start with the ethic of getting it down and seeing what you learn, here’s the therapeutic part, what you learn along the way, that in fact, it’s really a book about voice. And we don’t actually really need his name because it’s not about that. I’m not saying you hide the details, but I’m saying they change in value. So let’s write the first draft first and see what we’ve got.

Joanna: I love that advice. And again, I think that’s actually the same for any book that you end up writing because we’re all like, ‘Oh, I’ve got this idea,’ and it’s like, yeah, sure, ideas are nothing. Execution is everything.

And this memoir, I’ve got an idea for and then when I walk towards it, I’m like there’s nothing there yet, it’s not there. But it’s like you said about people thinking that a book might be about them, they are the hero of their story so they think your story must be about them. But, of course, it’s not necessarily because you’re the hero of your story. So I love that, it’s brilliant.

Marion: It’s fascinating to see someone look up from their life.

I’ve worked now with thousands of writers literally and I’ve worked with so many during the real crescendo of me too in the very beginning of it here in the United States at least before we had these hearings for the Supreme Court justice, Justice Kavanaugh, which literally I have not gotten an email since the Kavanaugh hearings in two years. Well, I’ve gotten a few, but in the run-up to that, I was getting them after the first major big high profile arrest in America.

My email box was just flooded with people saying, I have never told my story, I’ve waited 38 years to tell it, I want to tell it now. And then when the Kavanaugh hearings, which seated, and Supreme Court justice who’s been accused of sexual abuse which seated him as a Supreme Court justice, my email box went silent again.

Now that’s a very bad sign. But what I found fascinating was watching someone look up from the story during it two months in, five months in, and having them say to me, ‘I think this is a book about finding my voice.’ Oh, well now we’re talking. Because voices, as you know, as a writer, everything.

Joanna: And when once you start writing, as you say, you might find the thing that it’s really about. And at some point, I will set aside time to do the memoir I want to write, but as I said, it might be a while.

Marion: Now you’ve told me. So I am going to be sending you little emails.

Joanna: A little reminder every now and then. But let’s talk about something that when I think about this, specific detail is always important in any genre actually. But with memoir, as you say, it has to be based on our life.

I feel like the line between memory and truth, like what I remember and what is true could be completely wrong. And also, if I remember a conversation, some kind of emotional resonance of a conversation but I can’t remember the actual words said or the actual place where that was said:

How do I strike the balance in a memoir between memory and what really happened and then just adding stuff based on it being 1986 or something?

Marion: Absolutely. Well, you’ve covered about six really good topics in that question and they’re easy to really negotiate because you’re talking about detail.

Detail is currency and when I read your story, I enter your country just like I do when I travel and I cash out my currency for yours and you get to put coins in my pocket.

But before I leave your country, I want to have spent every single one and what I’m spending them on is learning your argument that peace can be found in my own backyard. I’m not an Eat, Pray, Love person, I’m a garden-at-home person and find peace.

So I could write a book from my own backyard that shows you that I can have a transcendent experience back there. So I’m going to give you the details of my transcendent experience back there.

Beads on an abacus is the way you want to think of your details if you don’t want to think about them as currency. You want to put something to use. This detail plus this detail plus this detail illustrates this argument, it adds up to this argument.

Details are very important. You have to curate carefully from your own life to only show me or give me the coins or whatever metaphor you want to use, show me the details that add up to your argument.

You have to remember that your details are not the same as your sister’s details. Christmas, 2004 was the worst Christmas of her life, it was the best one of yours, right? ‘What?’ she says. ‘Do you remember that uncle Willie got drunk and fell down on the pachysandra?’

And you say, ‘Oh, I must have missed that. I was so busy making out with my boyfriend on the couch.’ Very different Christmases. And so that’s so important.

What details are you going to give me to navigate? You’re going to give me yours. It is wildly subjective, I only care about your point of view. And if you don’t remember those details, you can ask your sister about Christmas 2004, but she’s going to tell you her version, you’re going to have yours.

I always say to people, do your research.

What does research look like for memoir?

It means asking your sister, but expecting that the experience was different, don’t let that stop you though, it can mean looking in your high school yearbook, it can be looking in your college yearbook, you can do research on your house, you can do research on your neighborhood, you can do research on your neighborhood association, you can go back to your primary school.

There are ways to reassemble the names, and dates, and places because everyone thinks memoir doesn’t require research, it requires enormous amounts of research. You want to check your facts, why? Because you want to get it in context.

That’s a long answer to details which are very specific, curated, chosen coins that the writer puts in the reader’s pocket that reflect the writer’s point of view but that have been heavily researched so that we get what it was like to be alive in 1995 or 1956 or 2004, that they’re accurate.

And don’t worry about having a bad memory, you can research anything these days, but make sure you do good research and get it right.

Joanna: And a little tip; keep journaling. I’ve got journals since I was about 15 and those early ones are just shocking. They should never see the light of day. But at least I can go back and go, wow, you talked about God when I was 15 and had a conversion experience. I really loved God so my journals are just full of this stuff.

It’s really interesting because you almost feel like you’re visiting your old self. And so since then, I’ve really been careful, I don’t journal every day, I don’t do morning pages or any of that, but I journal regularly enough that once when I decide to go back and pick things up then I will have a letter from myself at that point.

Marion: Great. It’s wonderful. And there are so many ways to do research, letters that your parents sent to one another or as I said, yearbooks. There’s a whole realm, but to understand why you’re doing it is essential to get it right.

Journals are great, diaries are fantastic, photo albums are rich as they can be, sit down with your sister with the photo album. And there will be some agreement, at least you’ll agree on the name of the family dog, I promise.

Joanna: You’d be surprised.

Marion: As soon as I said that I thought, ‘Nah, no,’ I have a sister. But I was telling a story at a dinner party recently that my sister was at and I told this story and I thought it was hilarious, of course. And at the end of the story, she looked up to a party of 11 people at a dinner and she said that never happened.

Joanna: That happens to me all the time with my brother and or my mom. It is exactly as you say about the different memories of an occasion, make people feel in a different way.

That is another question I wanted to ask about emotional resonance because I feel like one of the resistance is the resistance I feel towards writing memoir is that no one is going to care, like why would anyone care about this? Even taking the example you’ve said about your garden, finding peace in a garden, how do we make people care about that?

You talked about the universal at the beginning, but how do we make sure that people care?

Marion: When I read a book that has somebody going hand over hand up an ice face mountain in Nepal, I don’t do so because I’m going to do that, I do that to feed my sense of human wonder endurance, resiliency. And I feel a 100% sure that it does that exact thing, that it’s challenging my sense of resiliency or endurance.

How you get them to care is constantly keeping in mind that universal because we are not reading your book for what you did, we’re reading your book for what you did with it and that is the huge secret of memoir.

We’re not reading your story for what you did, we’re reading your story for what you did with it. And if you can keep that in mind at all times, you will be successful.

Joanna: Those are some great examples. And I wonder, because you obviously, as you mentioned, you’ve seen thousands of these books over the years.

Are there any other common issues that you see in manuscripts as a coach? What should we look out for?

Marion: Common issues in memoir are several, one of which is dialogue. People, as you mentioned before, don’t remember what they said, you want to remember that you’re reconstructing dialogue. And, of course, you weren’t keeping a notebook unless you were a very strange little kid at eight years old, you weren’t keeping a notebook.

But I do keep one now everywhere I am. I have one tied to the gearshift of my car, I have one in the bathroom, I have one next to the bed, I’m writing things down all the time but you weren’t when you were eight.

So you’re reconstructing that dialogue. What that means is you don’t ever make yourself more clever, more intelligent or wittier than you were in the moment.

In fact, it’s so human not to have a retort, right? Somebody dumps you on the street, somebody literally breaks up with you on the street when you’re 15 or 18 or whatever, you probably weren’t very clever when they did that, you probably were silent and crushed, right from the accurate intent.

Remember, always go in with that intent to be accurate. You probably didn’t say anything, you probably grabbed something out of your purse. You probably went to the nearest pizza parlor and shoved an entire pie in your mouth.

Show us the real, don’t make yourself out to be something you never were. We can smell that a mile away and we can smell it in dialogue more than anything else.

Dialogue reconstruction is very, very important. If your parents sat you down when you were 13 to tell you that they’re getting divorced, you probably remember who was angry, who was crying, and who was quiet, and just reconstruct that.

You remember the basics of the conversation because you know the personalities of those people involved. And also with dialogue, people hang way too much off the ends of their quotes.

They say things like, ‘No,’ she said with a slight smirk on her face that indicated that she’d heard this kind of memory before or she heard this kind of dialogue. No, no, just floating on a page is all you need.

With memoir, in particular, I find that people just attach so much to their quotes that we lose the power of language. And a good, well-placed no, tells volumes of characterization, of what was happening in the moment, so that’s one of them.

I think that’s probably the most important lesson I can impart with people is keep the dialogue brisk and don’t hang anything off of your quotes.

Joanna: That’s a good one. And I actually did quite a lot of screenwriting training and wrote a few screenplays, not they went anywhere, but that helped me because the rule there is if you give a script to an actor, do not have things in parentheses like (angrily).

You should be able to convey that in dialogue and through action. And that’s exactly the same as you say, in memoir, it’s not explaining how people are meant to say things. That’s fantastic, I never thought about that with memoir.

I want to just shift gears a little bit because I want to ask about marketing. This podcast is very much for authors who do want to sell some books. Obviously, there is a great reason just to write memoir, it doesn’t mean it has to sell any copies and it’s very worthy anyway.

In terms of marketing memoir specifically, what have you seen in the genre that works?

Marion: What I’ve seen is being a bit brave. I saw a book the other day that wasn’t memoir but this made me just delighted. It was a field guide to mushrooms, to fungi.

Joanna: I think I’ve got that.

Marion: And the author took, I think it was a him, his copy and made it, got it really wet and left it in a dark and nasty place and grew mushrooms all over it and then took a photograph of it. I just love this person. It was so meta that I kind of had to put my head down on the table and say, ‘Oh, that’s so funny, that’s so, so, so funny.’

I think it’s a great example of what can you do that’s different? I think that in memoir, we think that people just want to hear our story when in fact, again, they want to hear what the story tells us. What about mercy? What about the relationship in-between dogs and humans?

To market your memoir, well, what you want to remember is it lives really there in your subtitle. What is the value proposition for the reader? What am I going to get when I read this? I am not reading it for your story. I am not, please, trust me, I’m not.

I’m reading it for my own sense of wonder or mercy or forgiveness. So what can you market in that one little word? What have you got? Can you do a little video? Can you get me an Instagram series that teaches me about mercy? About the many qualities of mercy and draw me in.

I’m fascinated by the things I’m seeing on social media and how good people are getting at teaching me small lessons on mercy, let’s say in an Instagram stream that allows me to realize the value proposition of reading this entire book, so it’s that. Go into that, what I call the X factor, and really dig into it, that word that’s going to be in your subtitle that gives me that value proposition, and find a way to make me think that you know something that I need to know.

Joanna: It’s really the nonfiction topic that’s below the memoir. And it is interesting because, of course, the memoir I’m thinking about is a travel memoir and that’s why I started my other podcast, which is ‘Books and Travel.’ I actually interviewed quite a lot of memoir writers because a lot of people write memoir about travel. So I did that in order to start building up an audience for the memoir that I may write one day, which is quite funny.

But I did want to ask you about podcasting in particular because you have a podcast ‘QWERTY’ which I have been on.

Why did you personally start podcasting and how has it helped you in your business?

Marion: I started podcasting because I wanted to have more conversations with writers. I am still living a solitary lifestyle as I have been for many, many years as a writer. I work with writers all day long, one-on-one or in classes that I teach. But what I wasn’t having was conversations with my peers and that was really missing from the people who have just published and have new insights into how do you get it out there? How do you be the person you are on the page?

That’s a question I asked Richard Zacks, who is a historian of vice. He’s a remarkable writer, a whole lot of bestselling books, but he was a kid who grew up in New York city going to peep shows. And literally, like those things that we weren’t supposed to go to, he’s very honest about it.

The only thing that interests him is vice and he’s written a remarkable series of books that include the history of vice in America. Well, people don’t have any encouragement to do that. He grew up in a fairly traditional Jewish household in New York, not conservative, but not crazy liberal.

So I needed to talk to someone about how you give yourself permission to pursue what you really love to be a writer. I needed to have a conversation with you about how do you ignore that terrible advice about, you better specialize, young lady, or you’re never going to get anywhere.

Because you sure as heck haven’t specialized like that and stayed in one little pod, you’ve tried all kinds of things. And I want to talk to people who are publishing so that’s what got me to start a podcast — my own curiosity.

How does it fold into my brand? It’s about how to, it’s really about giving other people, presumably young writers, tips on how to write from themselves, how to ignore the bad advice, how to do research. So the topics each week take on something else that’s a how-to.

Joanna: I think that’s great because I feel like a lot of people think that they are going to podcast for marketing reasons. I’ve been doing this for a decade now, this show, and the last time you were on, it was like eight years ago. But we get something from the conversation that’s not just about marketing, right?

We learn something new or we think something different after the conversation.

Marion: Yes, and I think that you have to constantly go in with wonder. I’m endlessly curious about how to have a writing life and there’s just no end of combination to it.

I have a friend who’s 92 who’s I think the greatest living American writer, William Kennedy, he’s an astonishing writer. He’s 92 years old, he’s currently writing a novel and a play. He’s also caregiving his elderly wife and he’s got kids, and a house, and stuff. That’s a whole other conversation is aging with your own ideas. He’s fascinating on the subject of endurance.

I have a friend named Russell Banks who’s one of America’s great novelists. He writes 365 days a year. I have seen him leave the dinner table when he’s done and go back to work. His discipline is astonishing. He also only writes one page a day but it’s 365 pages a year. And he publishes some of the greatest-reviewed novels there are.

So what do you learn from each of these? Something that you didn’t know and going in with that kind of intent, you’re going to have fun too. And it shows, your show, you’re having fun, you’re learning, I’m learning. I never want to stop learning.

Joanna: Me too. And I think that’s why I’m still doing this show and why you continue with ‘QWERTY.’ But you mentioned endurance there and I want to circle back to what you said at the beginning when we asked about your background.

In 1983, when you left ‘The New York Times,’ so running your own business and being a full-time creative, since then, and you mentioned building a business around a book. I want to ask you about longevity and endurance and all those people listening who want to make a living with their writing, what does a business around a book look like?

What does a business around a writing life look like for you?

Marion: I previously published three books through three of the biggest publishers in the world, Houghton Mifflin, Bloomsbury, and Grand Central published The Memoir Project most recent one, and Simon & Schuster, published another book. Before I had gotten to Grand Central, I had published with big publishers. I’d had the traditional experience, the advance, the book tour, lots and lots of experiences and I learned a lot.

But what I also learned is, what if you did it the other way? What if you threw something down for the public and you said, ‘Now I’m going to build something out of that.’ In other words, the book isn’t the only product, it’s not the only widget here on the table.

I knew if I challenged myself to write a book on how to write memoir and then backed it up with an online business, I’d have myself an adventure. And so that’s the word, adventure, this might as well be an adventure.

I say to writers every day, you better love the work because if you really are just thinking about making millions from your publication, you are going to be disappointed. It’s not just that you’re not going to make the millions, it’s that you’re going to be disappointed because you’re not going to love the process. And it’s the adventure of this, what have you got?

When I write, I feel like everything I’ve ever seen, tasted, thought, smelled, considered, every movie I’ve ever seen is being annotated and drawn up from this wonderful place, and that’s thrilling.

But every once in a while, you want to heighten that adventure just a little bit more and that’s what got me to start this business from the book was a greater sense of adventure. What else can I do?

I’ve seen the publishing model. I’ve done it. It’s great, okay. I’ve published with some of the most amazing places in the world. What’s new? What’s different? What’s hard?

I happen to love to work without a net. When I left ‘The New York Times’ everybody tried to talk me out of it. And I understood their concern for me. I was 27 years old. My mother was an Alzheimer’s patient, my father had just died. There was no guarantee of an income, but to me it seemed like the greatest adventure in the world.

So that’s a long answer to adventure, curiosity, and the endurance piece is keeping it new. What are you interested in?

My four books are four different topics, they’re all nonfiction. So keeping it new is what really, really interests me and that’s because you know better than anyone, when you write a book you’re going to have to spend some real time with it, you better love the topic. And again, to get back to my first answer, you better love the work.

Joanna: I just think no one is going to last very long doing this without loving the work. And like you mentioned discipline, and you asked me about discipline as well in our interview with me on your show and I think I also said then I never feel like I have discipline because I love what I do.

It doesn’t take discipline for me to get online with you and have this conversation because this is great. I’m really happy to do this anyway and it’s just a bonus that is also marketing, and income, and everything else.

As you say, loving the work and also a curiosity for change because goodness, things have changed in the publishing business since 1983.

Marion: Yes, wildly. And you might as well accept that. And the thing that I think separates a lot of people, strange as it sounds, is the technology, they’re afraid of it. So don’t be afraid of it, find out how to do it.

It’s not that hard to master one or two pieces of social media and put yourself up maybe just a landing page. So if you publish an op-ed, an essay somewhere, and I think, ‘Wow, she’s smart. I like her.’ I can find you and then I can find that you’ve got a book that you’re working on and maybe I’ll become a fan or better yet, a publisher or an agent can find that you’ve got a book that you’re working on and maybe they can contact you.

It’s just remembering that you do have to be found, you have to be able to be found these days, it is just part of the process. It was not when I started in 1983. It had nothing to do, unless somebody looked you up in the phone book. It wasn’t about being found. Now more than ever, it’s about being found and then compounding that name in a very positive way online so that we want more.

Joanna: Which is a great time to ask you where can people find you, and your books, and classes, and everything you do online?

Marion: That’s lovely, at marionroach.com. There are lots of classes, there’s lots of access to books, and essays, and everything else. It’s a big online site that now includes even a shopping cart and lots of recorded classes.

I started my brand as a live brand only, and the demand has been such that people really want to take the classes with them on their phones. Okay. So I just decided to record all the classes and put them up as well.

Joanna: That’s brilliant. And of course, the ‘QWERTY’ podcast which you can find in your podcast app. So thanks so much, Marion. That was fantastic.

Marion: Thank you, Joanna, and write well.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn