In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 188.

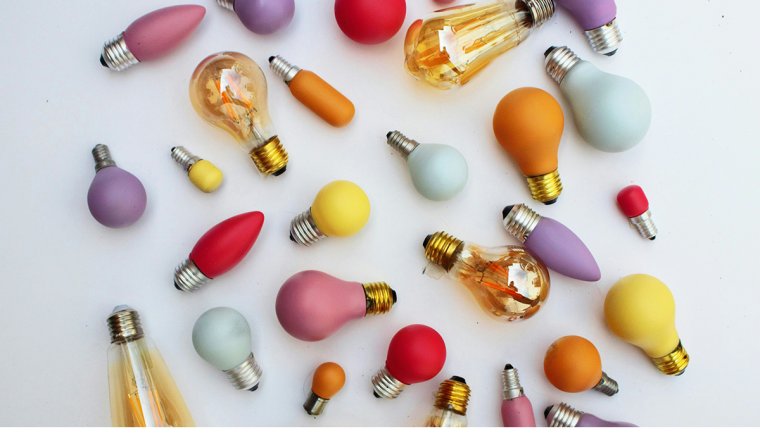

One of my greatest teachers, David Bosnick, used to say, “A title is like a light switch in a darkened room.” I heard him repeat that phrase many times to the eighth graders he taught, and I carried that saying with me into my life as a poet and teacher. A title is often a light switch: the first place you go to illuminate the room of a poem. In my reading and writing life, however, I’ve found that a title can also be a dimmer-switch, a dial, a circuit breaker, a live wire exposed and sparking. Sometimes a title isn’t wired into the structure of the poem at all. Sometimes it’s a satellite orbiting high overhead. Sometimes it’s a dose of poison that contains its own antidote. And sometimes it’s just a title: an empty placeholder, a name tag, an easily guessed password. Thinking deeply about how titles work over the years, I’ve come up with a list of ten categories for poem titles. Many of these categories overlap, and the list is by no means exhaustive. But hopefully the different types of titles I explore below will open some new possibilities for titling your own work.

1. Formal

A formal title calls attention to the form a poem is (and sometimes isn’t) written in; this is, of course, a metapoetic gesture. The poem might either subvert or strictly adhere to the form. Examples include: “Villanelle After Wittgenstein” by H. L. Hix, “Sestina: Travel Notes” by Weldon Kees, “pantoum: landing, 1976” by Evie Shockley, “Haiku” by Etheridge Knight, and any of Wanda Coleman’s American Sonnets.

The sestina and the pantoum have a substantial tradition of including the form in the title. Wanda Coleman’s use of “American Sonnet” in her titles—a practice extended by Terrance Hayes in his book American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (Penguin Books, 2018)—complicates, subverts, and invests with historical complexity the English sonnet tradition. Consider also Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Woods: A Prose Sonnet,” an early example of the American prose poem that adds to its frisson by invoking form.

2. Emblematic

In an emblematic title, a word or phrase works like a sigil or symbol for the poem. The emblem might introduce an abstract concept, a concrete subject, or a guiding metaphor that will be elaborated as the poem unfolds. Emblematic titles tend toward brevity and sincerity, and they tend not to be subverted in the course of a poem. Examples include: “Despair” by W. S. Merwin, “The Windhover” by Gerard Manley Hopkins, “The Bean Eaters” by Gwendolyn Brooks, “Good Bones” by Maggie Smith, and “My Son, My Executioner” by Donald Hall.

Emblematic titles are useful if you want either to err on the side of simplicity or to call the reader’s attention to a central metaphor. These titles are not flashy, but they often do complicated work, as does Hopkins’s windhover (a kestrel, which is a metaphor for Christ) and Smith’s repurposing of real-estate jargon for a meditation on the human power to act in the face of a cruel universe.

3. Anaphoric

Anaphoric titles involve repetitions—either by quoting a line that appears within the poem or within the poetry collection itself. Examples include: “Nothing Gold Can Stay” by Robert Frost, “Just Once” by Anne Sexton, “For the City That Nearly Broke Me” by Reginald Dwayne Betts, and “American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin” by Terrance Hayes.

Anaphoric titles might repeat within the poem, as in the first line of Sexton’s poem and the last line of Frost’s poem. Or they might establish a musical refrain within a larger work, as in Betts’s Bastards of the Reagan Era (Four Way Books, 2015), wherein eleven poems are titled “For the City That Nearly Broke Me,” and Hayes’s American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, wherein every poem is titled “American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin.” Repetitions of this kind can emphasize obsession (obsessive confrontation of a difficult truth, perhaps) and create the effect of a litany.

4. Expository

Expository titles set a scene and provide narrative details about the situation explored within a poem. Poets like Robert Bly and James Wright were inspired by the expository titles in ancient Chinese poetry. Examples include: “Waking from Drunkenness on a Spring Day” by Li Bai, “After Drinking All Night With a Friend, We Go Out in a Boat at Dawn to See Who Can Write the Best Poem” by Robert Bly, “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota” by James Wright, “On the Fatal Consequences of Going Home With the Wrong Man From the Chicago World’s Fair, 1893” by Amy Gerstler, and “Black, or I Sit on My Front Porch in the Projects, Waiting, on God” by Jameka Williams.

I admit I’m biased toward expository titles—the longer the better, especially when the poem is short and succinct.

5. Allusive

An allusive title references another text, artist, or work of art. Examples include: “Note Blue” by Kyle Dargan, “Self-Portrait as an Allegory of Painting” by Frances Sterle, “Girls That Never Die” by Safia Elhillo, and all of the poems in H. L. Hix’s book Perfect Hell (Gibbs Smith, 1996), which are titled after quotations by philosophers.

Kyle Dargan’s “Note Blue” apostrophizes Teddy Pendergrass, who was the lead singer of Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, Francine Sterle’s “Self-Portrait as an Allegory of Painting” invokes Artemisia Gentileschi’s painting of the nearly same name (“Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting”). Safia Elhillo’s title comes from a lyric by Ol’ Dirty Bastard. Allusive titles work like hyperlinks for meaning, summoning the world of another text or artwork and layering it into the frame of the poem.

6. Subversive

A subversive title defies the expectations and clichés it invokes. Examples include: “Come In” by Robert Frost, “Daddy” by Sylvia Plath, “acknowledgements” by Danez Smith, and “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note” by Amiri Baraka.

Robert Frost was a virtuoso of subversive titling. Many Frost poems do what “Come In” does, which is to seriously probe the intersection of grief and reason. The prosaic welcome articulated in the title subtly takes on more ominous associations, with death and dying, as the poem moves to its close. Plath lacerates the paternal term of endearment associated with childhood, controversially metaphorizing the Shoah in this “confessional” poem (although “Daddy” reads less subversively today than it did when it was first published). Danez Smith’s title parodically conjures the lengthy acknowledgements pages in contemporary poetry collections, moving from the title into a nuanced exploration of love, desire, and identity. Baraka’s title playfully subverts itself as it moves between light and dark, between joy and grief, between innocence and experience, initiating its readers into a profound chronicling of what it was like to be a Black father in the late 1950s.

7. Metapoetic

Metapoetic titles tend to be formal, emblematic, expository, allusive, and subversive all at once. Examples include: “Words Written Near a Candle” by Tess Gallagher, “Lines Written on a Splinter from Apollinaire’s Coffin” by Paul Violi, “Poem” by James Schuyler, “Prose Poem (“The morning coffee.”) by Ron Padgett, “Poetry Is a Destructive Force” by Wallace Stevens, “Poetry” by Marianne Moore, and “Words” by Ruth Stone.

Metapoetic titles call attention to the poem as a written and aural artifact, as Gallagher’s title does. Metapoetic titles might engage some element of poetics and poetic tradition, as Violi’s surreally does. These titles might reinscribe or fabricate the circumstances of the poem’s initial composition. They might challenge or affirm a definition of poetry as Stevens’s does, and as Schuyler’s, Moore’s, and Stone’s do more simply and directly. A metapoetic title might also embody the expanding cartographies of genre it professes to delimit, as Padgett’s title does so well.

8. Perspectival

A perspectival title unironically introduces a persona or frames a dialogue in the poem. Examples include: “Ellen West” by Frank Bidart, “Carl Hamblin” by Edgar Lee Masters (and most of the poems from his Spoon River Anthology, first published by Macmillan in 1915), “Mother to Son” by Langston Hughes, and “The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo” by Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Perspectival titles, like emblematic titles, function more like light switches than the other categories in this essay.

9. Fugitive

A fugitive title spills over, or “runs on,” into the opening line(s) of a poem. Examples include: “This Is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams and “here rests” by Lucille Clifton. Clifton’s poem begins:

here rests

my sister Josephine

born in July ’29

The fugitive title collapses the artificial boundary between title and text. The title is subsumed into the organic structure of the poem, and it functions less as a label and more as a first line.

10. Absent

Some of the most famous poems in the English language do not have titles; think of Emily Dickinson’s lyric shards. Refusing to title a poem may inscribe a gap, a gulf, a chasm at the poem’s start.

Much remains to be said about the art of titling. The possibilities for titling are more numerous than the names of our ancestors and descendants, as luminous, or, at least, as multitudinous as the stars in the sky. To poets who have trouble deciding on a title, I say: Try as many kinds of titles as you can. These titling strategies are not all light switches exactly, but they do flicker with meaning in the many rooms of the poems I love.

Dante Di Stefano is the author of four poetry collections, including the book-length poem Midwhistle (University of Wisconsin Press, 2023), Love Is a Stone Endlessly in Flight (Brighthorse Books, 2016), Ill Angels (Etruscan Press, 2019), and Lullaby With Incendiary Device, which was published in an anthology titled Generations (Etruscan Press, 2022) that also includes poetry collections by William Heyen and H. L. Hix. Di Stefano’s poetry, essays, and reviews have appeared in The Best American Poetry 2018, Prairie Schooner, the Sewanee Review, the Writer’s Chronicle, and elsewhere. With María Isabel Alvarez he coedited the anthology Misrepresented People: Poetic Responses to Trump’s America (NYQ Books, 2018). He holds a PhD in English from Binghamton University and teaches high school English in Endicott, New York. He lives in Endwell, New York, with his wife, Christina, their daughter, Luciana, their son, Dante Jr., and their goldendoodle, Sunny.

Art: Dstudio Bcn