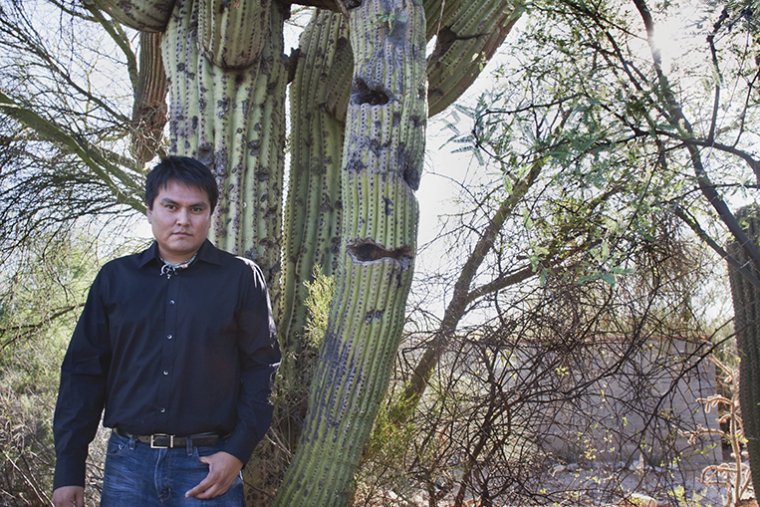

For Bitsui, the second of five children born to a carpenter and a teacher’s aide, living on the Navajo reservation meant the freedom to wander the land for hours, knowing he wasn’t trespassing. He would sit on the mesa for long stretches of time and meditate while listening to his Walkman. (His musical preference at the time was heavy metal. “It relaxed me,” he says, smiling.)

He was allergic to horses and to hay, so he didn’t become a ranch hand. Instead, he was introduced to the goat- and sheepherding life by his grandparents. It was hard work, but he enjoyed it and the company of his grandmother, especially during the summers, when he wasn’t getting bused to an elementary school outside of the reservation.

“School was the only thing I didn’t like while growing up,” he says. “It’s where I learned to become invisible among the white kids in order to survive.” He contrasts that tactic with the one most of the kids in the ArtsReach program resort to, which is to be loud and confrontational. “I guess neither one works,” he says.

For the past eight years, Tucson has been his home away from home, but adaptation was a shaky process. “When I first moved there,” he says, “it was my introduction to America. And it freaked me out.”

Bitsui initially left home in 1997, at the age of twenty-one, to attend the Institute for American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico. “I loved it there,” he says. “We were from all sorts of tribes but we were all Indian, and aspiring artists.” Bitsui wanted to become a painter, to capture the colors and textures that had given him so much pleasure as a child. But he lacked the skill. “So I decided on the next best thing: poetry.”

This was an unusual choice for a boy who grew up in a place where the nearest library was over forty miles away. Books and writing were not completely absent on the reservation, just scarce. “There were many stories around,” says Bitsui. “These stories made me see into other worlds that no longer exist. Worlds that were made alive in the retelling.”

Under the tutelage of poet Arthur Sze, Bitsui found his voice. “I remember those first awful poems I wrote,” says Bitsui. “To this day I’m grateful to Arthur for being so patient, for believing in me.” The IAIA, however, didn’t fully prepare Bitsui for what a writing workshop would be like in a public university. With Sze’s encouragement, Bitsui applied for and was accepted to the prestigious writing program at the University of Arizona. He moved to Tucson in 2001, and when he arrived on campus, he had a flashback to his “invisible days” during his early education—feeling marginalized among the greater student population.

“I had a meltdown,” he says, refusing to elaborate, except to say that it was the first time he experienced culture shock. The faculty and students in the program were well meaning, but he rarely found workshops useful. His lyrical, elliptical style was neither personal nor anthropological; it resisted straightforward narrative and folkloric characterizations. Few readers understood what he was doing, and he began to feel claustrophobic in the often insular world of academia. “The communities writing programs promote are true gifts to poets and poetry,” he says. “But it was important for me to find poetry and attempt to define it on my own terms outside of venues where poetry is maintained.” So just as he was about to complete his MFA degree, Bitsui dropped out of the program.

“At the IAIA, I didn’t have to explain where I was coming from, let alone where I was headed to,” he says. But from the painful awareness of his otherness came a body of work that would form his first poetry collection.

University of Arizona Press acquisitions editor Patti Hartmann heard about Bitsui’s poetry from members of Native American literary circles, such as Ofelia Zepeda, a linguist, poet, and MacArthur fellow, who is also the editor of Sun Tracks, the press’s Native American literary series. Hartmann called Bitsui to ask if he had a manuscript. Although he hadn’t finished his MFA, he did have a manuscript completed, which he sent to Hartmann. After several revisions, she accepted the book for publication, and Shapeshift was published in 2003.

The first lines of Shapeshift—“Fourteen ninety-something, / something happened”—refer to the arrival of Columbus in America and the beginning of a major shift in Native American history, culture, and life. For Bitsui, the new millennium, a few years ago, marked a time to reflect on whether Native people were surviving and thriving or heading on a path toward extinction. And the poems in Shapeshift—a collection of mythical journeys, dream images, dead ends, and reservation realities—explore this subject.

“I also wanted to reclaim that word, shapeshift, which has a different connotation to us,” Bitsui says. “It doesn’t only signify physical transformation by power or magic; it also means spiritual or social transition into a new way of being.”

Reviewers received Shapeshift with both skepticism and excitement aroused by its stylistic risks. “Some people were baffled by the book because it did not work in a way that was palpable to certain trends in Native American poetics; others liked it because it was new and distinctive,” Bitsui says.

After the book’s release, Bitsui found himself drawn into the national poetry-reading circuit and onto the international stage. Besides traveling all over the country, he has been featured in the Fiftieth Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte at the Venice Biennial with the Indigenous Arts Action Alliance, and he’s been invited to Colombia to attend the International Poetry Festival of Medellín with Joy Harjo. Most recently he attended Poesiefestival Berlin, where he read alongside Rita Dove and John Yau.

“Every day’s a gift,” Bitsui says, pondering the opportunities he’s had. In 2006 he received news he’d won a prestigious forty-thousand-dollar Whiting Award. At the time, though, he was in the middle of writing an elegy for his cousin. Because his family was grieving, he didn’t want to encroach on their grief with his news, and neither did he understand the magnitude of the prize until he was sitting on the stage in New York City, listening to his work being praised.

When he returned, having made the trip alone, he attempted to describe for his grandmother this place he had visited, where crowds flowed through the streets and the buildings reached high into the sky. “Oh, you went to New York City,” she responded. Bitsui chuckles at the recollection.

As the new face of Native American literature, Bitsui takes his responsibility seriously, which is why he doesn’t turn down any offers to travel or read poetry or be interviewed. “Though I hope I’m not the only one being asked,” he says. He names two of his contemporaries, poets Santee Frazier and Orlando White, who released books earlier this year. Frazier published Dark Thirty with the University of Arizona Press, and White released Bone Light with Red Hen Press.

“I’m excited that there’s a new group out there, but I worry about what’s expected of us,” Bitsui says. He admits that one thing he’s been disappointed by in many of his presentations is the comparisons that audience members will make between him and the Native American superstar, Sherman Alexie.

“Sherman’s charismatic and funny,” Bitsui observes, “but there’s only one Sherman. The rest of us should be allowed to be who we are.”

When we finally arrive in Bisbee, it’s painfully obvious what happens when a place attempts not to change. This old copper-mining town tries to remain the same in order to cultivate tourism. The old brothel is now a hotel decorated to resemble a brothel, and the saloon’s decor includes stuffed javelina heads and hunting rifles. Most of the residents of Bisbee are white, as are the visitors. The original buildings along the main street now house expensive art galleries.

We take a walk to a copper mine, the entrance fenced to prevent tourists from leaning over the edge. “They say that one time water pooled at the bottom,” says Bitsui, “and that a flock of Canadian geese flying overhead detected it and swooped down for a drink. The water was toxic, poisoned. And the next day, the bottom of this mine glowed fluorescent white with the dead pile of birds.”

And as if on cue, it begins to rain again. “Perhaps that’s why I gave my second book that title,” Bitsui says. “The poem is a song that floods, ebbs, and is searching for a name. I feel that it’s a body of work that speaks a third language, combining Navajo sensibilities with English linearity.”

This poetic hybrid is also what attracted Wiegers to Bitusi’s work. “That was another word-of-mouth phone call,” Bitsui says of how Wiegers first contacted him. “I met Michael briefly at an Association of Writers & Writing Programs conference. I was introduced to him by Matthew Shenoda, the Coptic poet. And Michael eventually called me up out of the blue to ask if I had a second manuscript.”

Wiegers wanted to hear Bitsui off the page, so in 2007 he accepted an invitation to the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, where Bitsui was a fellow that year. “I arrived at the conference the day after he read,” Wiegers recalls, “so I pulled him aside and asked him to read a poem to me. We walked down to the pond, where I sat on a big rock while he told me nearly the entirety of the new manuscript, which was still in development. I was impressed, to say the least. I suggested to him that when he finished and was looking to publish the book, he’d have a ready ear in me.”

As we take cover in the local coffee shop, a musician starts to set up his equipment. We are determined to make it to the saloon to have a beer once the rain stops.

“With Flood Song I wanted to go back to my beginning as an aspiring painter,” Bitsui says. “I think of many of those poems as portraits with their own elliptical stories to tell.”

Bitsui says that his ideal readers are visual artists, who discover something of their techniques in his writing style. But he confesses that even his family members are puzzled by his poetry. “They’re waiting for me to write a poem they can understand,” he says, laughing.

In the meantime, Bitsui will continue to live in Tucson, where he has been most productive in his writing. And while he’s scratching out a living as a visiting poet in various tribal schools in the area, he’s also moving forward with other projects. He has decided to return to the University of Arizona to complete his MFA and to finish a screenplay he’s been struggling with since he received a fellowship last year from the Sundance Native Initiative to adapt one of his stories for film. Bitsui doesn’t consider himself a short story writer, but as a descendant of storytellers, he couldn’t refuse the opportunity. The Sundance programmer, N. Bird Runningwater, has been patiently waiting for Bitsui to turn in the script. “It’s not poetry, though, which is hard enough,” Bitsui says.

The beer at the saloon (more like a movie set) is anticlimactic, so after one drink we head back to Tucson, making a brief stop in Tombstone, home of the O.K. Corral. It’s Wyatt Earp Days in the town, and the locals are capitalizing on the occasion with a street fair selling cheap Native American jewelry and charging for a chance to ride in a covered wagon, old Wild West style.

“I once brought my grandmother here,” Bitsui says. “And I remembered her stories about riding in a wagon in the old days, so I asked her if she wanted to relive that memory by taking a wagon ride. She said, ‘Been there, done that. It’s not a very fun ride.’”

We find our way back to I-10, going west this time, riding off into what will become the sunset. It’s been a pleasure being on the road, talking story. But all good things must come to an end. Bitsui needs to return the car by sundown. It’s a rental.

Rigoberto González is a contributing editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.

(Photos by Jackie Alpers.)