As writers, we use tools every day — from the laptop we write on, to the internet we research with, and the social media sites we use to reach readers. We are used to using digital tools to enhance our author life, but could we really work with artificial intelligence to push our creativity to new levels? I talk to Max Frenzel about AI in today’s interview.

In the intro, Bookshop’s anti-racist reading list; US bookstores support the protests [Publishers weekly]; and UK initiatives [The Bookseller], Dr. Isioma Okolo’s video [Dr. Isi and Rod]; FindawayVoices launches AuthorsDirect; Join the Virtual Thrillerfest if you want to write better thrillers; US Patent Office rules that AI cannot be recognized as an inventor [BBC]; Microsoft lays off human journalists in order to use AI [The Verge]; Natural language model GPT3 released [Venture Beat]; Using AI as a creative tool, Australia won the first AI Eurovision song contest [The Verge]; Race and technology [VentureBeat];

Do you need help with marketing, publicity or advertising? Find a curated list of vetted professionals at the Reedsy marketplace, along with free training on writing, self-publishing and book marketing. Check it out at: www.TheCreativePenn.com/reedsy

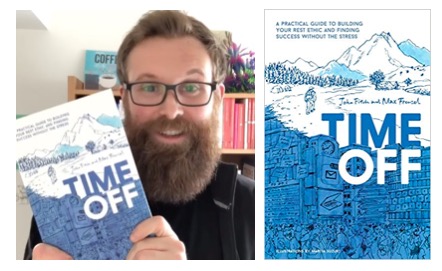

Max Frenzel has a Ph.D. in physics and is now an AI researcher on computational creativity in Japan focusing on the creative applications of AI in art, design, and music, as well as how AI will shape the future of work. He’s also an author and his latest co-written book is Time Off: A Practical Guide to Building Your Rest Ethic and Finding Success Without the Stress.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- What AI is capable of doing right now in writing and creativity

- Dealing with copyright when working with AI

- How AI could affect the book ecosystem and where our books fit in it

- What the impact of the pandemic might be on AI development

- How busy does not necessarily mean productive

- What is a ‘rest ethic’ and how can we apply it?

- Why mental crop rotation matters for creative people

You can find Max Frenzel at TimeOffBook.com and on Instagram @mffrenzel

Transcript of Interview with Max Frenzel

Joanna Penn: Max Frenzel has a Ph.D. in physics and is now an AI researcher on computational creativity in Japan focusing on the creative applications of AI in art, design, and music, as well as how AI will shape the future of work. He’s also an author and his latest co-written book is Time Off: A Practical Guide to Building Your Rest Ethic and Finding Success Without the Stress. Welcome, Max.

Max Frenzel: Thanks for having me. It’s a huge pleasure to be on, I’m a huge fan of the show.

Joanna Penn: Thank you. I’m very excited because you know this is a favorite topic of mine.

First up, tell us a bit more about you and what led you into AI research around creativity.

Max Frenzel: That was actually quite a convoluted way of getting into it. I originally did my Ph.D. in quantum physics, so I did that in London many years ago. And during my Ph.D., well, I really liked research, but I realized I’m also very good at the entrepreneurial side.

Also, I just wanted to do something more applied than just really abstract math, essentially. And after I finished my PhD I thought, ‘Okay, what field can I go into where I can use my math skills and actually make some real progress on, well, real-world problems?’ AI seemed like the best choice at the time and I think it still is for many people going that route.

At that time I joined a small start-up in Tokyo focusing on AI for business applications. I was doing many natural language processing on, for example, helping business analysts do a better job find insights and news. But I was getting a bit tired and also the company situation, company culture wasn’t exactly aligned with what I really believed in and also what actually then eventually led to this particular book we’re talking about.

At the same time, I was always interested in the creative side and I was doing art on the side, I was producing music, I’m still producing music and performing.

Eventually, for various reasons, also the company culture, I decided to quit. A friend of mine who had been doing a start-up related to AI and creativity for many, many years and he’s been kind of pushing me for a long time and saying, ‘Hey, Max, don’t you want to join, don’t you want to join?’

At that point, I thought, ‘Okay, now is finally the time.’ And I said ‘yes’ to him and that’s kind of how I got into the whole AI and creativity field. I’ve been in that for, well, really actively full-time for about a year now, but I’ve been slightly in and out of the field for, say, two, three years.

Joanna Penn: That’s fascinating. I think it’s really important to note there that you’re producing and performing music, so you are being creative, you’ve written a book.

We’ll come to the AI and creativity specifically in a minute. But, so, we’re recording this in lockdown at the end of April, 2020. And the world changes very fast in AI research, but let’s just kind of try and give a snapshot right now. Because ‘AI’ is such a broad term, right?

Max Frenzel: Absolutely.

Joanna Penn: Right now what is AI capable of doing and what is it not capable of doing, specifically for writing or creativity?

Max Frenzel: That’s a very good question. As you said, ‘AI’ is such a broad term and it’s thrown around a lot. Probably the most capable term or what people usually mean when you talk about AI is machine learning or deep learning.

Essentially what that is, it’s really just a fancy way of doing statistical analysis. So while it is extremely powerful, at the core of it is really just statistical analysis. Which is actually interesting if you think about it from a creative point of view because, yes, these algorithms can find insights in massive amounts of data and find interesting averages in a way, but as creatives what we’re really looking for are outliers of the data.

I think that’s what will still make creativity, human for a very, very long time. What AI can really do is help us in that, but we’re still the curators and we’re still eventually the people who decide what is art and what is not.

In terms of writing, you hear a lot in the media, but also as a researcher in the field I want to warn everyone a little bit. What you see in the media and what’s actually going on are two very, very different sides of it.

There’s a lot of hype and often what gets out is very pushed and polished by the marketing departments. So a lot of these things we hear about sound incredibly powerful and very nice, and, like, AI writing entire scripts of screenplays and novels even. But I’m very, very, very skeptical having worked in that field and still working in the field.

Essentially AI currently, in terms of writing, is very good at highly structured language and also a very, very short-term context. When I worked on the business side of things and really working on this AI for business analysts and looking at news data, what we found is that the more structured a language is the easier a time AI has at actually getting information out of that.

For example, legal texts are very, very easy for an AI to understand because it follows very strict patterns and has very clear rules.

When we were looking at Twitter data, on the other hand, it was basically impossible to apply the same methods. And even though you as a human might think, ‘Oh, for me a tweet is much easier to understand than a legal text,’ but it’s, again, this pattern spotting and this statistical analysis.

There’s much fewer patterns in Twitter data, there are a lot more typos, there are a lot more variations, language changes constantly. So that’s actually very, very hard for AI to do, even at such a short-range. And as we go to longer and longer ranges of text it becomes almost impossible.

And what I like to think of AI in the creative fields, it’s really a tool for exploration. So I like to think of the example of Photoshop.

When Photoshop or similar graphic design tools came around, people worried that graphic designers are going to lose their jobs. But the exact opposite happened really. Those people who embraced those new tools, they could automate a lot of tedious tasks and allow themselves to explore the space of possible designs much, much faster.

And you can think of similar kind of spaces of potential in every field you’re doing. So in writing, for example, you think of all the books that could be written, basically all the combinations of letters or words or whatever minimum of element you’re looking at, and essentially what we’re doing as writers all the time is wandering through the space of all possibilities and we’re narrowing it down and trying to find, ‘Okay, what’s the direction I want to take? Where do I want to go?’

I think AI can help us navigate that space much faster, but in the end it’s still us deciding on the direction we want to go in and in the end deciding on what is art and what is good writing.

Actually one interesting example where I saw someone actively using AI in a more artistic side of writing, just before the whole world shut down at the beginning of March I was actually in Montréal leading this AI Art Lab organized by MUTEK Montréal.

MUTEK is one of the world’s leading festivals for digital art and electronic music and they were organizing this 10-day workshop where they invited 15 international artists, and I was the technical facilitator of that workshop. And one of the artists, Lucas LaRochelle, based in Montréal, many years ago started a project he called Queering The Map.

It’s essentially an interactive website where you can go and leave stories anonymously on a map, on a global map, and really just any kind of queer story, like people are sharing, ‘Oh, I had my first kiss in that place,’ or just random things. Very short ones, also longer ones. He’s been running that for a long time and he’s become very popular in the queer community and he now has over 60,000, I think, of those submissions.

What he did with the AI was recently he trained a system on all those different submissions and had a system that could generate new ones of these. Now most of them are complete gibberish, but he just generated a lot of them, and then curated them himself and combined them with very interesting artworks, actually street view images but also regenerated by AI.

So it became these very, very surreal queer stories with these dreamy images in the background and he turned it into a live performance where one of these appears on the screen and he reads it out and he has a friend of his performing live music on top of that.

I think that’s a very, very interesting example. But again, it was a lot of human curation in the process and also it’s very, very short. And the shortcomings of the AI are actually very deliberate, so they’re almost part of the performance. The fact that those stories that come out of it are not very realistic or that they’re slightly off this kind of uncanny value where you’re not sure if it’s human or machine, that really lends to the artistic performance.

But I think what we see a lot with these kind of systems, a lot of them work very, very well in 70% of the cases, and that’s good for a researcher. The thing that actually gets out to the public is just, ‘Okay, AI made this and now, I don’t know, all offers are going to be replaced with this thing.’

But we’re far, far away from actually having these more complex systems come to a level where they’re commercially stable enough that they can actually replace a creative human. And I actually don’t think we’re going to come there any time soon.

Creativity is really about connecting distant dots.

And what we have now as AI is what we call narrow AI, so it’s very, very good in very specific areas. And there we can really make use of AI and help us in those specific areas, but it’s going to be up to us to make the more distant connections, find a meaning that connects all those different things and really make the final artwork, essentially, make the final writing, make the final whatever we’re working on.

That’s how I see the future of creativity and art in general. Now I think there’s a lot of much more, well, exactly kind of narrow application where we can really use AI. I’ve also not been looking into this particular space, the language side of it, too much recently, so I’m just going to make some things up maybe.

I just finished editing my book and one thing I used all the time was a thesaurus. I could imagine easily a much, much smarter AI thesaurus. Because, again, it’s the statistical analysis parts, you can train it on particular data sets.

For example, I could train one of my thesauruses on your particular writing. If I have a sentence and I want to change the word, I can ask it, ‘Okay, what is a statistically likely or what are other statistically likely words in that context?’

But I can also ask it, ‘Okay, what are other statistically likely words in that context in the writing of Joanna Penn?’ for example. So that could be a very interesting thing where some kind of human element and this interaction with AI comes in to, again, use the AI as a tool.

I think also maybe, I don’t know if someone’s actually looked it up, but one area of research is keyword or keyphrase extraction from longer documents. I think in a research process this would be incredibly powerful and valuable.

As a writer, so often during your research, you have tons and tons of text to read. If you could have a system highlight in advance the key phrases, that would probably help you a lot and I think that’s very, very doable and very well within reach if just someone puts some time and money behind this. Also, I guess, I think Amazon, you probably know better, but Kindle, they actually know which passages are highlighted by readers. Right, that’s a thing?

Joanna Penn: Yes.

Max Frenzel: I could totally see a system trained on figuring out in your draft which passages are very likely to be highlighted by future readers. And that could then give you a sense of, ‘Okay, where can I improve?’

But maybe you probably don’t want every sentence to be the highlighted one because you also need the connecting material. So, again, it’s a bit of human curation in the process, but you can use AI as a tool to help you in that process. Sorry, that was a long answer.

Joanna Penn: No, it’s great. I let you run there because I was writing lots of notes, but we’re going to have to circle back on a few of those things. Loads of great stuff there.

I want to first come back on that queer story map because I completely agree with you, I don’t think we’re going to be replaced by some human-like AI that’s going to do what we do. But what that guy did there was take lots of people’s little stories, and then use AI to do this curation, and then create something new.

And then you also mention the AI thesaurus which could be trained, say, on the writing of Joanna Penn. This is the issue for me because, as you know, deep learning has to be trained on a data set.

Max Frenzel: Yes.

Joanna Penn: I have two different opposite views on this. Which is, one, I desperately, desperately want some of these writing AIs to be trained on a complete data set of all books because at the moment they’re all trained on dead white guys writing over 100 years ago and we’re not getting any of the modern voices, different voices, different genders, different races, etc. But the other side says, ‘Well, what about copyright?’

And so the question here is that guy who created the queer story map stuff, if that was turned into a book, where is the copyright for AI, for that generated work? Is it with him, is it with the person who created the AI tool? What about the people who wrote the original works?

And the same with your AI thesaurus idea, what happens if a big publisher uses their data set of books that they have licensed to train an AI? Do those authors get anything?

At the moment there’s been one case, right? In China, copyright was assigned to an AI for a nonfiction journalism piece [Venture Beat, Jan 2020]

How do we deal with this copyright idea and also the training idea?

Max Frenzel: That’s a very, very good question and I’m not sure if I’m going to have a good answer for it, actually.

Joanna Penn: Well, nobody does, it’s just your opinion!

Max Frenzel: I think first of all what should be said is, one thing you pointed out is very, very important, very true, the way those models are trained depends extremely on the data they’re trained on. And this huge bias is baked into these models because of that.

Now actually in the AI art community this is one of the big focuses which people are really trying to stress. Because as artists one of the things we always do in the art community is actually break the models on purpose. So we try and push those commercially available models sometimes or models we trained and made ourselves, but then try and put them to their breaking point or beyond.

That’s where the interesting art happens. A lot of this is really focused on this bias issue and really just making it so extreme that everyone becomes aware of it and also just making art in the process.

Now the copyright issue, that’s much, much more tricky. I don’t know. Like a traditional thesaurus, someone put that together, as well, right? And they were inspired by some writing before them. They looked at traditional texts to come up with that. I don’t know how it’s actually done in practice, but I’m sure there is this kind of process happening somehow.

So I don’t know how you could argue that a system that is trained on exactly the same kinds of texts should suddenly have different copyright issues then. I mean ultimately this language is out there in the public domain, I’d say, because it’s not…

Joanna Penn: But that’s specifically the stuff… Let’s take the example of the guy with the queer map where people who are alive wrote stuff and that is their copyright and he fed it into a model and created something new from that. And he might not have made any money, but if he could, he could put a book together.

Where are the rights for people who created that original stuff?

And again, there is no law on this at the moment. One of my ideas is that there is some kind of blockchain management of books so that there’s some kind of micropayment assigned to the books that are read into a model. So if a publisher, say, read in a million books, a million books are assigned some kind of micropayment.

And then if the model, whatever the model uses, a bit like the page read idea with the subscription services, there would be some kind of tracking that way. Because otherwise, I do see that people’s work will get fed into these models. And you’re right, we all feed things into our brains and we’re not…I’m not giving Stephen King any money for some of the stuff my brain. But I’m a human and the amount of stuff I can read in is very small.

So I think it’s this bigger picture about this is going to happen, this is happening, this is not out of copyright work, so what do we do with that? What do people in the artistic community want, do you think?

Max Frenzel: I think the boundary there is very, very difficult because everything is inspired by something else. Like if you put together a book, it’s built on other books, you’re reading a lot of other books, as you said. You might not be able to read as many different books, but at the same time you probably synthesize them in a much more because you don’t ingest so many books, each of those actually probably influences your writing much more than, say, an AI that’s trained on the works of hundreds of thousands people. Which really than just is an average of all those different things. Same with, say, painters or any graphical artists, they were inspired by other works, sometimes very, very obviously.

Now is their new work, if it’s different enough, a copyright infringement? I think it’s a very, very difficult topic. I know Seth Godin actually very recently talked about that on his podcast, as well. And now he’s very actually anti-copyright in a way because he really believes… I’m just paraphrasing him the way I remember, so don’t quote me on that.

But he believes that the copyright should just be there to actually incentivize creatives, it should not be any more restrictive than it needs to be to do that. A lot of people would still do their work if there wasn’t any copyright. Those people who submitted their stories to this Queering The Map project, they would have still submitted them if they knew what would happen with them, or at least 95% of the people probably would have. Some of them might have contributed even more because they’re happy to contribute to this bigger thing, what’s then built on top of it.

Now I don’t really know if that answers your question, but it’s just some thoughts around this. But as you say, it’s a very difficult issue and I think it’s going to be very tricky because it’s just such a sliding gray zone in between. It’s very difficult.

Joanna Penn: I agree. I really think the first thing that needs to happen is that publishers need to add a clause to contracts that say, ‘We may use this in a model at some point and part of my license is that I’m licensing your book to be used in some kind of model.’ Because I just think it’s inevitable.

Let’s move back to the keyword and key phrase extraction tool that you mentioned, which is something I’ve always thought, to me the book itself is metadata. And if you had a combination of your AI thesaurus plus an AI keyword extraction tool, then the AI could read in my book Desecration, for example, and it could tell from the writing where that book should fit in the ecosystem and it should aid discoverability.

At the moment we have to, when we publish, choose seven keywords and we have to choose some categories and we have to decide where the book fits in the ecosystem. But actually I think there’s much more interesting stuff that could be done with this, a combination of the tools that you suggest.

Do you think maybe Amazon is doing something like this already or do you think this is a long way off?

Max Frenzel: That’s a very good question, I haven’t really thought about that. I’m sure Amazon is using the data they have through Kindle, at least to do research. I don’t know if they’re using it in practice yet, but Amazon has one of the largest AI research teams in the world and I am very, very sure that they are actively working on those kind of things.

One thing you mention, so one of the things where AI is extremely good at, right now even, is similarity comparisons between different types of data. For example, like the tag suggestions in photos on Facebook, very accurate. And that’s really just similarity comparisons of images, ‘Hey, I know this face, I think this face is the same, so I suggest you tag that person.’

In some of my work before I was doing similar things with texts, so we used, for example, a news article and we could then look for similar news articles. And you could do the same with longer texts even, either by breaking them down and looking for similar paragraphs or using some slightly other techniques and doing it really at the book level.

What you said is actually very interesting because then you can look, ‘Okay, what are clusters of similar books?,’ or you could say, ‘Hey, here is my draft, show me the five most similar books which are above a certain success ratio.’

So you could see what are the most similar books which have been successful in the market. And then you could learn all sorts of things through that. For example, what Amazon keywords did they use or how did their marketing campaign or whatever. I think that’s a very interesting direction, but I’ve got no idea if anyone is actively looking into that.

Joanna Penn: I know several companies that I’ve talked to privately are doing this comparison of books that have similar keywords in the reviews because reviews can be pulled off Amazon itself and used textual analysis on. But I’ve tested some of them and I felt like, ‘Well, I could do that quicker myself in about five minutes.’

So I think it’s funny because I think there’s a long way to go, as well, but I’ve literally been saying the book is metadata for probably eight years now. And I feel quite frustrated sometimes because there’s so much potential in this, and yet clearly the author and book community is just not financially as viable as…and/or, let’s say, as important as things like medical research. So fair enough.

Max Frenzel: Well, I guess it also depends who are the players in the field who are interested in that. I think the only one who could actually do it and has the data and the money to put behind it would probably be Amazon.

Joanna Penn: Exactly.

Max Frenzel: If anyone is doing it, it’s probably them.

One thing you mentioned is that the review analysis was based on keywords. One of the key things of more modern AI, so really deep learning and machine learning, is that we can step away from just keyword matching, that’s one of the key advantages.

We really start looking at context and actually understanding the meaning of longer phrases in a way. So it’s not pure keyword matching, it’s actually matching of meaning. Because AI understands if I paraphrase a sentence in using completely different words, but I feed that into a well-trained model, the model will still understand that they are almost the same sentence even if they have zero word overlap.

I think that’s one of the big things we’re moving towards and which is quite important to distinguish between this more traditional keyword matching approach and more modern AI and deep learning.

Joanna Penn: Now, as we mentioned, we’re recording this during the lockdown. My feeling is that this whole situation is going to accelerate the development of AI, particularly also with automation, robotics, because people get sick.

And also, we’ve seen ‘AI-powered,’ in inverted commas, companies can make more money with fewer people. Now the ethics of this are a different matter.

What do you think the impact of this pandemic is going to be on the AI community and the development and speed?

Max Frenzel: I do agree with you that it will definitely have a positive impact on AI in the use of automation. But I actually see that as a very positive thing and I think a lot more people should see it the same way.

I think now a lot of us are forced into this forced time off, essentially. And one thing that probably becomes apparent for quite a lot of people is that a lot of the time we’re just performing this busyness, so we’re actually trying to compete with the machines at being busy. But no matter how much time you put into it and no matter how hard you work, you’re not going to out-busy the machines.

I think people who are realizing that now and shifting their focus on the more human skills is really this connecting distant dots, focusing on creativity, and also focusing on empathy, and using the time freed up by AI tools and other automation tools to reinvest in those ideas, they will really benefit in the future. So I actually think that using these tools more will really allow us to become more human and actually do much, much greater things.

Now, as you said, there’s probably a lot of ethical issues there, as well, and in the short-term, there will be a lot of disruptions. But I think it’s a very good time for people to just step back and reflect where in their lives they could be easily replaced by machines, essentially where do they focus on creativity and where is it more things that can be written down and, well, explained as rules which is something that’s very easy to feed into an AI.

I like to use the comparison of classical music to improvisational jazz. Classical music is very, very difficult, but it follows very clear patterns. I am actively working on AI music and in that space and most of the experiments are done on classical music just because it’s very easy to figure out these patterns. It’s, again, the same as the legal texts are much easier that the tweets.

Whereas improvisational jazz has such a human element and you have to constantly live with uncertainty and it’s a completely different way of approaching things.

I encourage people to think in their own lives or their work where do you do the equivalent of classical music and where do you play the equivalent of improvisational jazz, and maybe focus on the latter. It doesn’t mean that classical music is easy to do, it will just mean it might be less valuable as a skill in the future.

Joanna Penn: Ooh, nice. I like that. Classical versus jazz. I’m not standing here thinking, ‘Okay, what is left in my life that is’… And it’s so funny though because even… So our discussion, even though you’re German, you have a tiny accent, tiny, tiny. I have an English accent.

And still when I use an AI transcription for this interview, it will struggle and it does so much better with American voices. If it’s two Americans, it gets it almost perfect. And a Brit and a German, it will have difficulties.

I would love to not even have to check the transcription. I feel like I shouldn’t have to do that at this point, but I will have to. But that to me is ‘classical work.’ It is not classical music type work in that way in your metaphor because I shouldn’t have to even check the transcription at this point, but I will.

Max Frenzel: Then again, just a couple of years ago you would have still had to sit down and actually transcribe that yourself, right?

Joanna Penn: Yes.

Max Frenzel: So we’ve already moved a good step ahead. And probably in a couple of years, we’ll be there where you can pretty much trust systems to do a good job.

Joanna Penn: Yes, exactly. You mentioned forced time off, which brings us nicely to your book, Time Off, which is really suggesting that I could achieve more by doing less, and you talk about this thing called a rest ethic. Now as a workaholic, I need your help.

Tell us a bit more about what you mean by rest ethic and what the book is about.

Max Frenzel: Maybe actually the first part to start is actually the time off. And you said ‘by doing less,’ and, yes, that is part of it, but it’s not necessarily the only part of it.

When we talk about time off, we don’t just mean relaxation or sitting on a beach sipping a cocktail. There’s much more to time off. And you might describe yourself as a workaholic, but actually you might already be pretty good at practicing time off and have a very good rest ethic.

One of the examples in the book is Derek Sivers, writer, entrepreneur, musician, all sorts of things. And he said something along the lines that basically he optimizes life for creating and learning. And he actually says the word ‘workaholic’ would apply to him, but it’s all play, not work. And I think that’s really the key idea.

What’s important to realize and what’s really the core of the book is this idea that busy does not mean productive. And it comes back to the whole AI idea, as well. Busyness is easy to automate, it’s not very valuable. Often it’s actually counterproductive, especially in the creative fields.

More and more what’s left for us, what’s useful, and what’s valuable is this creative aspect. So really accepting that that busyness is not productivity is really, really a key focus.

And another key concept of the book is…we actually borrowed it from Aristotle. He had this idea of noble leisure. A lot of work can actually even fall under noble leisure. Basically it’s defined as meaningful tasks. And contrary actually, a lot of what people think they do in their leisure, I don’t know, sitting on their phone just scanning down their Facebook feed, is probably not noble leisure, it doesn’t fill their life with meaning.

You say you’re a workaholic, but I’d actually say probably a lot of the work you do is noble leisure in this way we define it.

And that’s really where your rest ethic comes in. It’s basically becoming conscious of how you invest your time. And, yes, we all have a work ethic and we want to get stuff done. But just like you need to complement an in-breath with an out-breath to be sustainable and healthy and balanced, you also need to complement your work ethic with a rest ethic. And especially on the creative side.

Rest ethic is really the incubation, the stepping away to seeing the bigger picture.

The retreating in solitude and doing reflection and those sort of things, they fall under rest ethic. And especially, I think, in times like now people are forced away from the busyness.

A lot of people are struggling for various reasons. A, probably being removed from the busyness just reveals this void in their life and this absence of meaning and meaningful leisure and hobbies that they so far just plastered over with busyness all the time. But now a lot of people are realizing that investing in meaningful tasks and meaningful hobbies is very valuable.

Also, cycling through different types of work can actually be time off. I’m sure you’re not working on the same thing, I mean you’ve got your podcast, you’ve got your writing, you’ve got different types of writing. Sometimes you’re in editing mode of one project, sometimes you’re in the writing mode for some other.

Søren Kierkegaard had this idea of mental crop rotation. So every farmer knows that you should not plant the same crop every single year in the same field. And Kierkegaard essentially took the same idea to his working habits and he rotated the work he was doing so his mental soil could essentially become more fertile again.

What I really like about this analogy is if you do crop rotation right, one type of stuff you plant in your fields actually fertilizes the ground for the next crop you plant. The same really happens if you do this mental crop rotation.

If you step back from one thing to either engage in true leisure, I don’t know, go for a walk, cook something, travel, or if you engage in other projects, it really fertilizes your mental ground, your mental soil for all the other things you’re working on.

I know you’re really into traveling. Something we’re talking in the book about, as well, is this idea of the traveler’s eye. When you go to a new country, everything is amazing. And even going to the supermarket is an adventure and you see these creative things everywhere and you get new ideas and inspirations from everything.

If you can keep this traveler’s eye, and really time off and reflecting and taking a step back helps you preserve that even if you’re not traveling, that’s such a powerful thing for any creative.

It’s also very closely related to watching kids at play. They have this amazing playground mentality where everything is possible. And, sure, you still need to do the serious work and actually sit down and verify all those crazy ideas, but a lot of people don’t even have those silly ideas in the first place or are not willing to talk about those silly ideas or admit them.

I think all these things need this aspect of time off to nurture. It’s really difficult sometimes to step away from work and just relax or guilt-free work on something else, work on a passion project. But you have to realize, and that’s really where the rest ethic part comes in, that doing this does not hinder your main work, it will ultimately feed back into it and make it much, much more valuable.

In the future, I think we need to focus much, much more on quality than on quantity. Because, again, AI is going to do the quantity and automation is going to do the quantity. What’s left to us is being creative and being human and focusing on human connections, understanding each other, and really doing quality work for each other.

Joanna Penn: I do walk a lot and I do sleep a lot, so I’m going to say that involves my rest ethic. But it’s interesting, this morning on my walk I took my little dictation Sony thing and I did half an hour of dictation of just some things I’ve been thinking about.

I have to get away from my desk in order to think that big picture. So that kind of combines, like you say, that getting away, and also thinking.

And I agree with you, I think this time of pandemic has made people really face up to, ‘What am I doing?’ I’ve got a great life and a great job, but I still feel like there’s lots of things that I shouldn’t be doing and things I want to change coming out of this time, which is really interesting. And the book is beautiful, it’s really gorgeous.

Max Frenzel: Thank you.

Joanna Penn: Just tell us about the process of the book and why did you make it so beautiful.

Max Frenzel: The process is actually quite interesting. If you would have told me two years ago that I would be writing a book, I would have probably told you you’re crazy. I never had the idea of writing really until it was really when I was doing AI research in that first start-up out of my Ph.D.

During my PhD, I had these amazing and I really am really, really grateful to my supervisors at Imperial College in London who really allowed me complete hands-off approach.

Basically I had three years to do my Ph.D., at the end, there was a thesis deadline, and what I did with the time in between was completely up to me. I could disappear to other countries for weeks on end without actually asking anyone for question…or permission.

I really made a lot of use of that freedom. I did a lot of side projects, engaged in a lot of hobbies, did a lot of traveling, started a company at the time, as well, actually. And all these different things.

And then being in that start-up, suddenly I became busier and busier and also less and less productive. And, again, it was travel, I was away from my actual work when it really hit me one day that, ‘Hey, okay, something is wrong.’ I never felt less busy and at the same time, less productive.

Just to help myself understand what was actually going on I started writing and I started posting articles on Medium. And somehow people liked my writing and started writing about all sorts of other topics, including AI. And my now coauthor, he, through some random chance, saw one of my articles on AI and creativity. He then looked through my other writing, one of which, one of those articles, was about the idea of time off and everything that the book is now about. And at the time he was doing a podcast on the idea of time off.

He reached out to me and asked me if I want to be on the podcast, and from there on we slowly became friends, kept chatting. And, again, through various random coincidences, I mentioned one day by chance that maybe one day I do want to write a book. And a couple of months later I had this e-mail in my inbox, ‘Hey, do you want to write this book together?’

That’s how the whole thing started. And the interesting thing is actually until today we have never met in person. I live in Tokyo, he lives in Austin, Texas, and the whole thing was remote collaboration.

I think that’s, again, a really amazing kind of sign for the future of collaboration and technology can allow us to do these amazing things if we use it on our terms and if we use it right. Yes, it can be a huge distraction and completely ruin your time off. But if you use it in the right way, it can allow you to do this, well, co-authoring a book without ever meeting in person.

Actually, also, you mention the book is beautiful, and that’s largely thanks to the amazing illustrator working with us on the book, as well as our amazing designer who actually makes the whole thing come together. But the illustrator’s story is also very interesting.

Very early on in the process, we decided we do want to have illustrations because it’s basically a bunch of deep dives on different topics, like creativity, sleep, reflection, solitude. And within those deep dives there are profiles, around 50 people, historic and present, who use these different ideas or aspects of time off and really were successful by implementing it in their own way. And because of the profiles, we thought very early on we would really like to have illustrations of those people in the book.

So both my coauthor, John, and I went on Instagram and actually just posted a story, ‘Hey, does anyone know good illustrators who might be willing to work with us on this book?’ And some person that I don’t know personally, she’s just following me on Instagram, reached out to me, ‘Hey, there’s this amazing illustrator based in Tokyo called Mariya Suzuki.’

Mariya, our illustrator, also didn’t know that person, so it’s really just some third person who follows both of us by chance and she connected us. And it turns out actually Mariya and I have a very close group of common friends, but it was this random stranger on the Internet that connected us.

Now Mariya is part of the core team of Time Off and doing those beautiful, beautiful illustrations and really completely shaping the brand image of the book and just making it absolutely gorgeous to look at. And, again, it was all just kind of random chance online, people coming together, that made it all happen.

Joanna Penn: Fantastic, and I love that. And I think just putting yourself out there and, as you say, asking the community, that’s exactly what has led to this.

Tell us where people can find you and the book and everything you do online.

Max Frenzel: The book is going to be out on May 25, 2020 and it’s going to be, well, every way you usually get your books. You can also find us online at timeoffbook.com.

And if you’re more interested in my personal stuff, like from my articles to my music to my art, it’s maxfrenzel.com. And I’m also on Instagram, that’s more the personal stuff. Like if you’re interested in me baking bread or growing mushrooms or making music, that’s @mffrenzel on Instagram.

Joanna Penn: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Max, that was great.

Max Frenzel: Thanks for having me.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn