How can anthropology — the study of human cultures — teach us to build richer and more convincing worlds for our stories? What questions do we need to ask of our characters and settings to bring them alive? Michael Kilman talks about how anthropology can help with world-building in this episode.

In the intro, the late Sue Grafton’s books licensed for film and TV even though she stated otherwise before she died [BookRiot]; Tina Turner sells IP rights [The Guardian]; Estate planning for authors; NaNoWriMo Storybundle; Pics from my St Cuthbert’s Way walk on Instagram and Facebook; Relaxed Author interviews – 6 Figure Author and The Indy Author; Focus on your strengths [Ask ALLi]

Today’s show is sponsored by IngramSpark, which I use to print and distribute my print-on-demand books to 39,000+ retailers including independent bookstores, schools and universities, libraries and more. It’s your content – do more with it through IngramSpark.com.

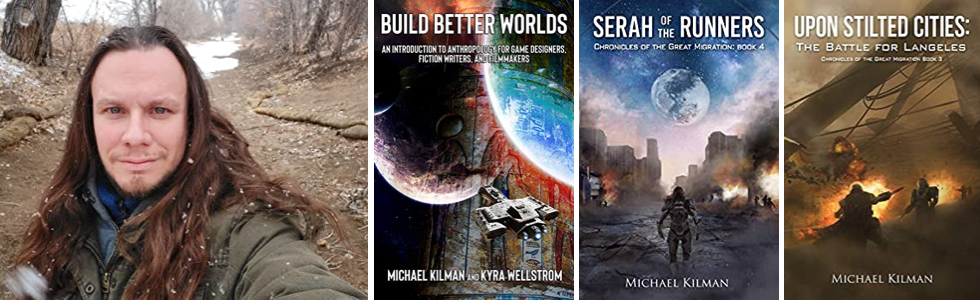

Michael Kilman is an anthropologist, filmmaker, artist, science fiction author, and musician. Today we’re talking about Build Better Worlds: An Introduction to Anthropology for Game Designers, Fiction Writers, and Filmmakers, co-written with Kyra Wellstrom.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- How knowing even a little bit about anthropology can support fictional world-building

- How artifacts reflect what matters to a society

- Important features of urban anthropology

- Cautions about info-dumping when describing a world you’ve built

- Thinking of cultures in terms of how the pieces work together to form a cohesive whole

- Writing about different cultures without straying into cultural appropriation

You can find Michael Kilman at LoridiansLaboratory.com and on Twitter @LoridiansLab

Transcript of the Interview with Michael Kilman

Joanna: Michael Kilman is an anthropologist, filmmaker, artist, science fiction author, and musician. Today we’re talking about Build Better Worlds: An Introduction to Anthropology for Game Designers, Fiction Writers, and Filmmakers, co-written with Kyra Wellstrom. Welcome, Michael.

Michael: Hi. Nice to be on the show.

Joanna: It’s good to have you here.

Tell us a bit more about you and your background and how you got into anthropology and writing.

Michael: I fell in love with anthropology in undergraduate after trying many majors, and really trying to figure out who I was. And on a whim, I took a class called Anthropology. I said, ‘Anthropology, what in the world is anthropology?’ Reading the course description it says, the study of human cultures. I was like, ‘Hmm, okay, all right.’

I took the class and fell in love. After that, I was just set on a path for studying other cultures around the world. I had already been writing for quite a while. I started writing when I was about 14, 15 years old, I started my first attempt at a book. It was terrible, of course, and so was much of my other work for quite a few years, I really didn’t publish anything fiction-wise until my 30s.

So it was a long process for me. But in the meantime, I went off to grad school in my mid-20s, and I started working with other cultures, I’ve worked with a lot of Native American tribes.

Over the years, I lived and worked in a rural village in Mexico, and a lot of like urban anthropology, which means we study populations, and cities, and stuff. My area of focus in anthropology ultimately became media systems and representation. So looking at how media represents people, and why is that problematic? Or why is it good?

All those various things, trying to uncover exactly what happens when you represent people in spaces like fiction, for example, although video production was in my background, and so I focused a lot on that kind of media at the time.

And then, a couple years ago, Kira and I ran into each other again. Ironically, we went to the same college as an undergraduate, but we never actually met each other until we were both teaching again at the same college we were both undergraduates in. So we met there, and we became friends, and we started talking.

Kira, she’s a biological anthropologist, which means she focuses on the biological side of culture, how does biology and environment impact humans? And her area of specialty is in forensics. If you’ve seen the show, ‘Bones,’ that’s the kind of stuff she does, although she doesn’t really like to be compared to ‘Bones,’ because there’s a lot of problematic science in that show, forensics is not so magical. And there’s a number of other things that are troublesome with that.

Although on the other hand, ‘Bones’ has made physical anthropology very popular, so we can’t fault it for that either. But we were both talking about how representation in fiction, or how a lot of these fictional worlds, they just don’t work, or they have big problems, they’re not holistic, like real-world cultures.

We started really thinking about it, and then one day, I was just like, ‘Hey, we should write a book on worldbuilding and use all of our anthropological knowledge, both of our graduate degrees to drive the book, and then also as a teaching tool.’

So we use a textbook version of this that we’ve created, which is a little bit different than the commercial version that people would buy off Amazon because it’s got a few more chapters, but those chapters focus on things like methodology, or things that you would do in the field that you wouldn’t necessarily be interested in for building a fictional world, and built-in quizzes, and all kinds of other stuff that textbook companies do.

Obviously, we have to project a little bit with alien cultures or elven culture, or troll culture, or anything like that. But understanding a little anthropology can go a very long way into building a more solid and immersive kind of fictional world.

Joanna: It is an excellent book. The book is incredibly rich, and there are many different areas that writers can explore.

For me, and many people listening who like thrillers, or action-adventure, or fantasy, there’s lots of things around artifacts, around seeking things, group of people go and find something. Obviously, talking would be a famous one, go and find something or go and return something and often called the MacGuffin in thrillers.

It was interesting because you have this whole chapter on the things we make and the things we leave behind. And that was really evocative chapter name as well. What are some of the things we can consider in this area?

Michael: Obviously you’re talking about films like ‘Indiana Jones’ or ‘The Mummy’; the idea that you have some sort of object you’re chasing. But our chapter is really more about the archeology of things like, and I think, largely what our chapter was trying to drive at is when you’re building a fictional world, you’re going to want unique objects in there.

If, for example, I mean, certainly The Lord of the Rings, you have the ring itself is a MacGuffin. But that’s such a present one because it’s everywhere. The whole story is about that one particular ring. But of course, a lot of thrillers are using more like, ‘We’re chasing this artifact,’ or, ‘We’re hunting it down,’ or those kinds of things. What does that object represent is a good question.

We have a section in the book on cultural purity, and talking about how in all arenas of life, we’re constructing these notions of purity, clean and dirty, right and wrong, good and bad. And we’re always measuring these ideas.

This comes from an anthropologist by the name of Mary Douglas. And so you should think about when you’re having the sacred object that you’re chasing around, not even necessarily sacred, but this object that everyone’s following around. George Lucas, uses R2-D2 and C-3PO as kind of like an interactive sort of MacGuffin in a way.

What does it mean to the culture that originally built it? What does it mean to the people who are chasing it? Those are the kinds of questions that obviously a lot of thrillers are asking, but how is it constructed? Or why was it constructed is another question.

In archaeology, we don’t just look at artifacts, we also look at features, which are kind of like the immovable version. A feature is a wall, or it’s a temple, or it’s a statue, it’s something not easily moved, it would take a lot of effort, or eco-facts, flora and fauna, those kind of things. What animals are around? What plants are around? What can we know about that stuff, right?

So it’s really interesting, because we always joke like with all these MacGuffins out in the world, that’s like the early archeology. The early archaeology was the adventurers, they were like, kicking ass, taking names, going around the world and doing a lot of looting really, quite honestly, not such very good ethical things in the early days of archaeology, a lot of very problematic stuff.

It’s known that the British Museum, even to this day has all kinds of issues with repatriation of artifacts that they took during the 17th, 18th, 19th centuries, and kept them in the British Museum. And it’s a lot of countries and cultures want their stuff back or whatever.

Early archaeology is about this kind of adventure thing. But it’s later on that, and I love to see a story like this, where you have these treasure hunters looking for this object. But in reality, they find out that the object maybe is not so important, but it’s what knowledge comes from the object because modern archaeology is not about the objects, it’s about what we can find out from them.

Kira and I, we had this wonderful archaeology professor undergraduate named Dr. Kent, and Dr. Kent had a saying, ‘It’s not what you find, but what you find out.’ In fact, it’s such a saying, I think two of my fellow undergraduates got it tattooed on them somewhere. So like, it’s another Ph.D. archaeologist, so they got very into that stuff.

Joanna: I think that’s really interesting, and asking these questions is so important. You mentioned that you have a specialty in urban anthropology and cities. And of course, our culture right now, a lot of stuff won’t remain of our particular culture. Because it’s digital, it’s technology, and it won’t be able to be found.

My iPhone could be found in years to come. But it will be like, well, ‘What is this metal thing? And what does it do?’ And it’s like you say, if it’s what you can find out, well, then you can’t actually find out because it’s all disappeared. I find that fascinating.

If people are constructing cities, what are some of the things that you think are important around cities and the urban anthropology?

Michael: There’s something so important, we talk about organizing government, it’s called political integration. And really, it’s how integrated is your city? Or how integrated is the political system with the day-to-day lives of people?

In class, the example I use is poop. Because if you think about it, if you’re in a small-scale society, and you need to poop, where do you go? You just go off into the woods somewhere. You dig a ditch and you’re done because you only have 40, or 50, or 100 people. It’s not a big deal. You’re not going to need to build a whole public works.

But if you look at a city and you think about what sanitation does. How many thousands of people it employs to deal with the sewers, to deal with public restrooms, to deal with waste treatment management, to deal with the power systems, to build or to collect and manufacture the toilets and the materials for the toilets.

All of this stuff, you’re talking about thousands of people every day, just to deal with sanitation, and sanitation is one of the most important things to managing a clean city. Because if you don’t deal with sanitation well, you get disease, and you get all kinds of other things that go very poorly for you.

I use that example, kind of comedically in class, I have students tell me all the things that they need to deal with, when you’re dealing with integrating a political system with waste management, but it’s also with everything.

When you’re building a city, you have to think about how are people going to get clothing? How are they going to get food? Where is it manufactured? How is it distributed? And really, it comes down to the fundamental problem of managing energy systems.

It’s also why people in this country, in particular, we talk about small government, small government, small government, and I know I’m sure they do in the UK, quite a bit too. But the reality is, once you reach a certain size of civilization, small government is laughable. You can’t not deal with infrastructure, it’s not a question of, if there’ll be a bigger government, it’s how big it will be.

Because there’s just so many things that you have to regulate to make power systems work, or organ waste management, or food distribution, in order to make sure that your population isn’t starving, or freezing to death, or all these other things, you have to do so many things.

And then, of course, the more technologically advanced you get, the more things you have to deal with, because now we have telecommunications, Wi-Fi, phone calls, we’re on Zoom here right now. And that has to be regulated to some degree in order for all the systems to work.

So if you’re thinking about building a city in another world, you’re going to have to think about these kinds of things, and what kind of systems are in place. And the one way that I got away with this in my own fictional series the Chronicles of the Great Migration is, one of my characters is a sanitation worker, for example. And now my series has a number of different main characters.

But I showed different faces of the city. And this is something you can try, and George R.R. Martin, Stephen King, a bunch of other big writers are really good at switching point of views between different characters that you get a bigger picture of culture.

Now, you don’t have to do it that way, of course, but I’m a big fan of if you’re going to make a really complex society, it’s really useful to show different facets of that, through different characters and different experiences.

Joanna: You’ve given an example there of a character who can see a certain thing. And also, I think it also has a practical application in terms of locations and settings. So you mentioned there, like sewers, I mean, sewers appear in loads of different stories as ways, a place that some marginalized people live, a place for people to travel without being seen.

I was thinking as you were talking about removing the dead, and in London here in Europe, when the plagues happened. Under Paris, you’ve got the catacombs, which are full of the bones of the plague dead, because what else do you do with them, and these sort of places where they stored the dead, and that’s because the city didn’t have anywhere to put them.

Or in London, the floods would lift the bodies up out the graves. And so as you say, and that is so rich, when you consider, okay, and I’ve written in one of my books, I have the Paris Catacombs, and then you think, ‘Okay, so why do they exist?’ And they exist for that reason.

So for people listening, it’s thinking about your character and giving a glimpse that way, and also your settings.

Michael: Yeah. And it’s tough, because when you’re doing world-building, and you want to do it really well, you have to be careful of info-dumping, like you can’t just dump all the information on it.

One way to do it is to show characters’ daily life, what’s it like to be just an average citizen who suddenly gets wrapped up in this big story inadvertently. It’s like the whole Hero’s Journey thing, the call for adventure from the farm boy, or a lot of those fantasy stories uses that kind of trope, where you have this kind of thing, but you can do that on all kinds of levels.

Your character doesn’t even have to be like the hero. He can just be the victim or she could be the victim of the circumstances of maybe war between two giant fantasy armies or something like that. It could just be the experiences of what is it like to be sitting there in the middle of a siege as trebuchets are launching into your city.

You can just give that feeling and drive a lot of tension and action simply by showing what it’s like to be a person in your city. You can even use that character for one chapter and then kill them off in maybe a prologue or something like that. I know George R.R. Martin loves to use like a prologue with a foreign character in Game of Thrones, and then kill them off at the end of the prologue.

And, it’s funny, because I was thinking about that the other day, when I was working on my next book. That’s actually a really clever way of doing something because it gives you a unique perspective. And then this is a character, not necessarily a character just to be discarded, but it shows you a slice of life that you wouldn’t have gotten otherwise.

That can be really powerful, and that can be really useful for worldbuilding. If you’re trying to show a picture or a side of your world that the main character just isn’t going to get to.

Joanna: I pretty much always use a prologue as well. In the one I’m writing at the moment, it’s 1000 years ago, in medieval times, for example, and then it jumps forward into now. But it’s interesting, because I feel like you could get so into all these details that you forget to actually write a book.

Michael: Oh, yeah.

Joanna: You mentioned problems with info-dumping there. And let’s be honest, you mentioned sewers, but I don’t put sewers in my books, I don’t need to. They’re just not necessary, so we don’t have to build every kind of aspect of a world.

Michael: No, absolutely not.

Joanna: If you were to say, right, if you just did these two things, your worlds would be better?

What are some of the things that you find writers are particularly weak at?

Michael: There’s no real easy, simple answer to that. Because obviously, everyone’s worldbuilding from a different point of view, or a different background of knowledge. But I think making your world holistic.

In other words, we know that in the real world, when something changes in one arena of culture, it’s going to ripple out into other arenas of culture. Think about how much has our culture changed, introducing the smartphone. Every arena of our lives has been altered by the smartphone. That’s the way with any introduction of any new idea or anything.

Now, of course, it’s a scalable. So small things, small changes, like the little pops in the back of our phones, the little handle things that people put on the back of their phone. Obviously, that’s going to change a few things, but it’s not going to have sweeping systemic change, because it’s already like an existing major culture change having the cell phone in the first place.

But a new religion coming to town would then affect the political life of people, it would affect gender systems, it would affect their sexuality, it would affect a class, for example.

In fact, when Christian missionaries go to town, a lot of times what they do is they completely disrupt the economic activity of people’s lives, sometimes on purpose, sometimes not on purpose. And then people who are of lower status will often take advantage of a new religion or a new ideology in town to gain advantage for themselves.

We see this all the time in indigenous societies, that a missionary comes to town, and it fractures the culture that’s established, and the people who maybe didn’t have access to society before suddenly have new access, and use that kind of power to change their lives in a lot of ways.

The number one thing I tell people all the time is, when you build a world, you can’t just throw together a bunch of elements, because that’s just not how culture works. You need to be thinking about how do these systems work together to make a cohesive, entire culture.

How does the religion integrate with your economics, with your political system, with identity in general? How does all this work on an individual identity level? What kind of challenges or changes are people going to experience when this change comes to town?

One thing we also know very well is, culture is constantly changing. And really the debate is over how much change will be allowed. Right now people who consider themselves more conservative, can have a tendency to be more fearful of these changes and new ideas. And so they’ll look back to this kind of imagine the glorious past and say, ‘Hey, we should go back like this.’ But there is no real going back.

And the people who are considered more progressive have a tendency, and again, these are trends or tendencies. Obviously, people are complex, you can’t just say conservatives do X and progressives do X, because almost everybody has some ideas that they’re progressive at, and some ideas that they’re conservative about, and that’s another thing to consider is you’re building these whole cultural systems, human agency, people make choices.

This is one way getting into avoiding stereotypes or getting these kind of places where we misrepresent people is, instead of just making someone a two-dimensional standard, stereotypical character, we give them complex choices and things. And those, holism and complex human agency, are the two big things that I think are so important that I think you can tell the difference between a good writer and a bad writer by those two things.

I honestly do think that, and that doesn’t mean that your worldbuilding is going to be perfect. No one’s worldbuilding is going to be perfect, because we all have gaps in our knowledge. We just can’t know certain things. And that’s why things like research are important into understanding in cultural systems. That’s why we wrote this book, so people have a better understanding of what is in a world.

Joanna: The other thing I think is interesting in terms of creating these worlds, and these can also be modern worlds; I build ‘a world’ for my ARKANE thrillers, for example.

There are certain rules and things like that, but we humans are the same across time. I take our current culture, sure, we have technology and stuff. But humans are behaving in exactly the same way as they did during other plagues and other threats in the End Times kind of millenarianism is what’s going on right now. It’s crazy.

Michael: Yeah.

Joanna: And you mentioned politics there. People think, ‘Oh, things are different now, because we’re so much more sophisticated.’ But we’re really not. I feel like you could put that, you can write a historical novel, and things will be different, but many things will be exactly the same.

You mentioned, fear, and conspiracies about plagues have always happened. Like it was that group or that group. And so, I would encourage people that you don’t have to reinvent everything from scratch.

You can borrow things from culture or periods in history, with the knowledge that people and/or aliens might behave in a similar way to how they did.

Michael: Absolutely. And what’s the name of that series, but it’s about dragon riders during the Napoleonic Wars, ‘Temeraire’, ‘Temeraire’ is the name of the book. So instead of having just the Napoleonic Wars, they also throw dragon riders, and dragons as kind of like this air force. It’s so fun because, and these are a young adult kind of book I read to one of my kids, and it just really does a good job of taking the different cultural dimensions.

Later in the series, they go to other cultures with dragons and see how the dragons are treated differently based on different cultural systems. And that author did such a great job of really just taking one big element, which is simultaneously a fantastical creature, and also a technology or a tool of war, and just showing what would have been different.

I don’t know what the author’s process was. But I think obviously, you can take the First World War with the fighter planes, and make some good guesses about what it would be like to have an intelligent, thoughtful dragon kind of creature intermixed with that whole system.

What are the hopes and dreams of dragons amidst this air core and all this other kind of stuff? And what’s unusual about this particular dragon or those kinds of things?

So, yes, absolutely you don’t have to reinvent the wheel, you can take a cultural system, look at how it’s holistic and say, ‘Hey, I’m going to throw dragons in there.‘ And then you can just think about, okay, well, what would dragons do to politics? What are the economic things that we need to deal with dragons? Would dragons change religion and how so? Would some people worship them or fear them, or consider them like the devil? How would all of this work?

You don’t have to get too super crazy. You don’t have to do what I did, which is build a world 1300 years in the future, with giant cities, and then try to figure out how that social system would work in an enclosed ecosystem. You don’t have to do anything like that. You can make small changes to historical periods or to the modern world.

A lot of people do this to zombie apocalypses. And just really try to understand what drives the change, who are the winners and losers is another good question to ask. Every society has winners and losers. So who are they? Especially when you add in a new technology, who would that benefit, and who would that disenfranchise? That’s another really good question to ask yourself.

Joanna: I was just looking up that book. That sounds awesome. This series is by Naomi Novik, and there’s nine alternate history fantasy novels about that, ‘Temeraire,’ as you mentioned, is the first one. That sounds awesome.

I think that’s actually a really good idea is to pick one thing that you can twist. I guess George R.R. Martin just took a historical novel and added dragons and zombies.

Michael: Pretty much. A lot of what he’s writing about, people say, ‘Game of Thrones is so brutal,’ Did you not read about medieval times?

Joanna: Yeah.

Michael: It’s a terrible, terrible time. People were just jerks. And women, they did not do well in that time period. So he does a really good job. His books are so good. I just wish he would finish the damn thing. That’s all.

Joanna: When you’ve been paid that amount of money, it’s like, why bother?

You’ve mentioned that you worked with Native American tribes, and you specialize in this idea of media representation. We’re living in a difficult time. A good time in that we’re trying to redress difficulties in representation within culture. But also people are struggling with that in trying to do it in an authentic way. And you are a white American man.

Michael: Yes.

Joanna: And yet you’ve written about all these different cultures, and many people are afraid of trying to write about different cultures for fear of being accused of cultural appropriation. And we also do want to write diversity.

I write very diverse characters in my books. And I don’t particularly worry about it to be honest, because I really try very hard to make it good. I also have readers who are from those cultures who read them and tell me if I’ve made a mistake.

How do you suggest that we can use aspects of culture without going over the line with cultural appropriation?

Michael: I mentioned a little earlier about agency. Agency in anthropology is defined essentially, as the ability to act within a given cultural system. So it’s not as if your choices are totally free or unlimited.

This idea of total free will is kind of like, well, how can you make a choice if you don’t know about something? Or how can you make a choice if you have a systematic oppression going on?

Agency is limited by the cultural system in a lot of ways or your choices are. One thing to think about, though, is like a Christian is not a Christian is not a Christian. You have many varieties of Christians.

They did a survey of the American Catholic Church a few years back on their political beliefs; how do they feel about things like abortion? Or how do they feel like things about gay rights? It turned out that on most of the major issues it was split pretty much 50-50 among American Catholics and all these issues that are fundamental to the church.

What does that tell you? That tells you that no matter what cultural system a person is born into, that doesn’t mean they have to agree with everything that the cultural system offers. This is why stereotypes are really dangerous, because in our minds, it’s so easy to categorize people and lump them in with an entire group of people forgetting that they’re human beings with thoughts, hopes, and dreams and all this other stuff.

We have a chapter in the book called, Why the hell did they do that: Understanding the context, conditions, and choices made by people in fictional characters. The reason we wrote that chapter is because when you’re writing about another culture, you need to understand the historical context in which this person is living.

What are the cultural conditions that their life is also in? And then what choices do they make? When we talk about context, that’s the history, that’s the language they’re born into, that’s really the system that they’re born into. The conditions are, what’s their individual experience?

I often use the metaphor of a city block, the context is a city block. The conditions are the house that the person lives in, and then the choices are their life within that house. One of the ways to avoid stereotypes is to consider, okay, here’s this cultural system. And that means you’re going to have to do research in the cultural system.

Especially when it comes to marginalized people, you really need to do your homework. That’s the first step, then you need to look at the conditions of that particular character’s life, what was it like to grow up?

Let’s say if you’re Native American growing up in American society, the conditions of your life are going to be very different than like someone like me, who is a white person who grew up in a suburban area of a city. Being on a reservation is a completely different experience.

What are the conditions and what are my conditions in the same culture versus that person’s? Then you can begin to understand people’s choices. And so using that model is helpful.

But the other thing that’s really helpful is things like sensitivity readers.

If you’re writing about a disabled character, it might be super useful to hire a sensitivity reader who, A, has the disability themselves, or B, works with the people who have disabilities, or at least has a background in studying those things.

A lot of the ways to avoid cultural appropriation is through the due diligence of research. And then also consultation with a culture, if you’re going to be writing about a particularly oppressed group, then it does not hurt to reach out to those groups to read as many books as you can on those groups, and really try to understand those things.

It’s just like any other thing in writing, it requires diligence, it requires discipline.

And if you want to be a better writer, then you have to do those things. If you just use lazy stereotypes, then, of course, you’re going to further the difficult situation.

And then when we’re talking about media anthropology, the one thing we see is how people are represented in long-term narratives. So not just once or twice in a book here or there, or even for a decade or two, but you’re talking about decades or centuries, how people are represented over time is how we come to think of them on an unconscious level. Our implicit bias.

When we’re culture appropriating, or we’re misrepresenting diverse populations, then we’re essentially contributing to those same stereotypes over and over again, and we’re furthering the difficult situation of those people.

It’s really important to consider what am I recycling? Or if I’m going to use a stereotype, like a certain group is in a certain economic position, for example, how is that useful? Is it useful because I’m trying to tell a story of the complexity of their identity? Is it useful because I’m trying to explain what that world is like for them? Why are you picking this particular character? For what reason?

You have to write diversity, you have to, unless you’re doing something very specific, like the Star Trek-style, where everyone is one, looks exactly the same in one side, and everyone looks exactly the same in the other. Unless you’re doing something specific to bring attention to issues of diversity, you have to write diversely, because the world is diverse.

You can’t go into any city and not meet a diverse group of people within a few minutes, who’s got different inclinations, thoughts, hopes, dreams, and all that stuff. So I think the most important thing to remember is that people are people wherever you go. They have to do the same things to survive and get through their day. But how they take that on, depends on their context and the conditions of their life.

Joanna: We’re out of time. But coming back to where you started, which is anthropology is the study of human culture, that has to underpin all of our writings. This is just a fascinating topic. I definitely recommend your book, Build Better Worlds.

Where can people find you, and your books, and everything you do online?

Michael: You can find us on Amazon. My book series, the sci-fi series, ‘Chronicles of the Great Migration’ is also on Amazon and Kindle. I am also now answering worldbuilding questions on TikTok, so you can find me, author Michael Kilman. I try to do a couple a week at least.

When people ask me questions, I do my best to answer them in a semi timely manner. You can also find my website where a series of anthropology called ‘Anthropology in 10 or Less.’ That’s all based on my website, which is loridianslaboratory.com. And, all my stuff is up in there.

Joanna: Okay, great. Well, thanks so much for your time, Michael. That was fantastic.

Michael: Thank you so much for having me on. You have a great show.

The post Build Better Worlds: Anthropology For Writers With Michael Kilman first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn