How do you successfully scale an author business? How do you delegate to your team as well as continue to research and write the books you love? With award-winning crime author, Rachel McLean.

In the intro, new Kindle devices [Amazon]; new European markets for Spotify audiobooks [Spotify]; customisable audio with Google NotebookLM;

Amazon Ads launches new AI tools for advertisers;

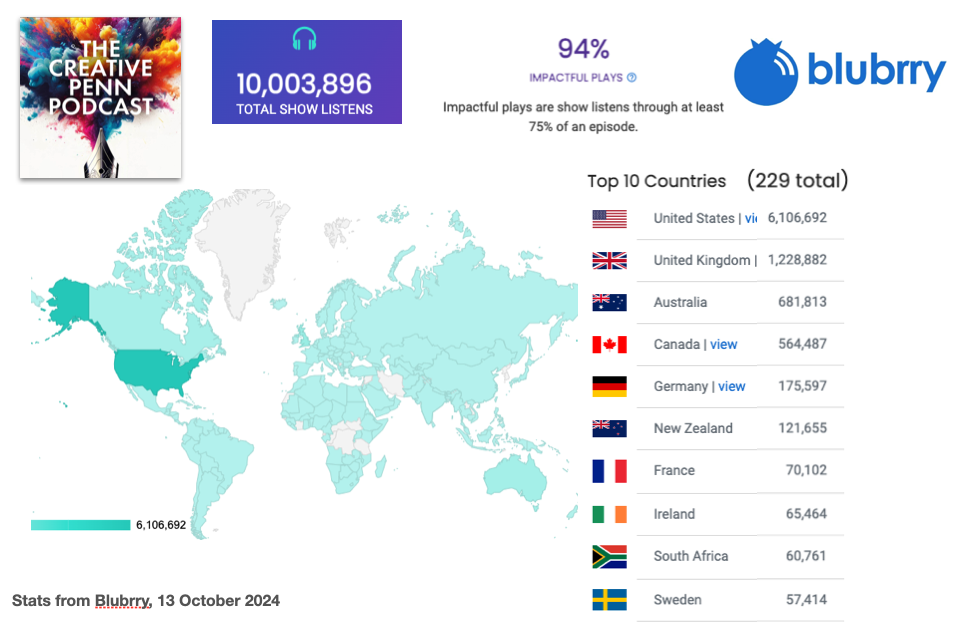

Enhancing Creativity with AI Tools [ALLi]; My Lessons Learned from 10 Million Downloads of the show; and Blood Vintage Kickstarter wrap-up.

Today’s show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, self-publishing with support, where you can get free formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Just go to www.draft2digital.com to get started.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

Rachel McLean is the award-winning author of the Dorset Crime series, as well as other crime books, and has now sold over 2 million copies.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Making the decision to scale your author business

- Hiring multiple freelancers with different skillsets

- Money and lifestyle as a source of motivation

- Writing with multiple co-authors and creating a small imprint

- How to write what readers want to read

- Moving your readers from KU to other platforms

- Selling audiobooks direct using Shopify and BookFunnel

- Using AI tools for location research

- Publishing videos on socials to humanize your brand

You can find Rachel at RachelMcLean.com.

Transcript of Interview with Rachel McLean

Joanna: Rachel McLean is the award-winning author of the Dorset Crime series, as well as other crime books, and has now sold over 2 million copies. So welcome back to the show, Rachel.

Rachel: Thank you for having me.

Joanna: I’m excited to talk to you today. Now, you were last on the show in November 2022, and we talked about how you pivoted into crime fiction. So we’re just going to jump straight into things today.

You started out with your Dorset Crime series, but you now have five series in total, and you work with multiple authors under your imprint, Ackroyd Publishing.

How has your business changed over the last few years?

Rachel: In some ways it hasn’t changed that much, and in other ways, it’s changed massively. So the core of my business, which is about writing crime books that readers want to read, I write in a very similar style. Obviously, my craft has developed over that time.

I’m really like doubling down on engaging with readers, I see that as actually, after the writing, my most important job because that’s the thing that I can do, and my team can’t do for me. So that hasn’t really changed, apart from the fact that it is scaled because I’ve got so many more readers now.

In the sort of day-to-day management of my business, that has changed hugely. I’ve now got a team of seven people who work for me. They’re all freelance. They each work a couple of days a week, and they do various roles.

I’ve got a publishing and production team, and they project manage all the books, do the cover design, pull all the files together, manage the editorial and so forth.

Then I’ve got a marketing team who help me run my shop and do advertising and data for me. I’ve got somebody who liaises with bookshops. I’ve got somebody who does AV work for me.

I’ve also got a number of co-authors who I work with now.

A lot of my books are co-authored with people who I’ve known for years and who I’ve been working with as part of my writing group for years. That enables me to sort of manage a bigger business, which takes up more of my time, while still producing more books now than I was able to produce without them.

Also, it’s really good fun, particularly on the creative side when you’re generating ideas for a new book or a new series, I get to work with other people.

So we’ll go for a trip to the location that the book’s going to be in, and we’ll walk around, and we’ll sit in cafes and things. We’ll chat about what’s going to be in the book, and we’ll come up with ideas. It’s really enjoyable.

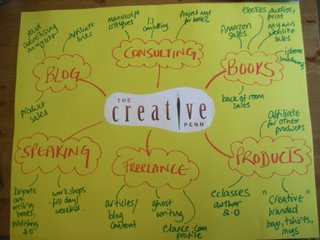

Joanna: Oh, so many follow up questions. The first one I have is—and this is quite a personal thing for me, and also people listening—because I feel like what you have done is you have gone from being an author to essentially being the CEO of a much bigger business.

Like you said, you have seven people you’re co-writing. So at some point, you made the decision, I am going to scale the size of my business and the income, obviously. You decided that there was something you wanted to do around running a bigger publishing company.

How did you make the decision to scale your business?

Obviously, it is a much bigger deal than, like me, I have not made that choice. It’s something I come up against over and over again, and I always step back from. It’s like I actually don’t want a bigger business. So what was that moment, so other people listening might be able to figure that out for themselves?

Rachel: Yes, it’s interesting because I always thought I didn’t want a bigger business and I didn’t want to manage people. I think that’s because my experience of managing people in the past had been in huge organizations.

I worked for government agencies and all sorts where it was very process driven. You had to do performance management on a certain day, and you had to manage people in a certain way, and you and they didn’t really have all that much freedom over what you did.

Whereas I’m finding that managing people within my own business is very different because A, I get to recruit them, and I get to find people who are a really good fit for my business and have got the skills that I need and skills often that I don’t have.

Then B, I get to work with them in a way that works for us, and it’s really flexible because we’re such a small business. It’s not like one person has a particular job title and they can only do that thing. People end up dipping into other people’s jobs, and we all work really closely together.

I get everybody together on a fairly regular basis. So we’ve got a Christmas lunch planned in December. We have an away event in the spring where we all go down to Dorset and have a couple of days together.

We have a summer lunch where we get all our editors and narrators and everybody, the whole full team together. So I found that I enjoy that much more than I thought I might. I really do enjoy it.

The point at which I had that light bulb moment, I guess in a way, I went to the 20Books Mastermind in Majorca immediately after Self-Publishing Show last year.

I went to that specifically with the goal of talking to people who were very successful, and had been very successful for a long time and were sustaining that. I wanted to learn from them because I was at a point where the Dorset Crime series had taken off.

The Kindle Storyteller Award had a massive impact on my sales, and I didn’t know how to sustain that. I knew that the workload involved in that was more than I could do on my own. At that point, I was thinking, well, I need to sort of clone myself.

I need to find somebody who would do all the business side of things.

I actually offered that job to my wife, and she turned it down.

Joanna: I’m glad she did. Saved your marriage!

Rachel: I’m glad she did now, as well, because we’re much happier having different jobs. She has a job. She works for the University of Birmingham, and she’s very happy doing that. It’s a whole different type of environment from what I do.

I went to the Mastermind in Majorca, and there was a talk on running your publishing business with a team. The light bulb for me with that was the fact that you don’t have to hire one person to do the business management.

You can hire multiple people to each do a part of it and to each work a certain number of hours. I already had a PA, Jane. She’s theoretically a VA, but she lives quite close to me, so she’s not all that virtual. We do see each other.

She was already doing some of the admin for me, but I needed somebody to manage the publishing process for each book. That was the thing that I was finding was a real sticking point for me because I have a terrible memory. I was forgetting what the deadlines were.

I was uploading books to the KDP Dashboard moments before I had to in order to fulfill a pre-order. I was really disorganized. I was thinking, how do I find this person who can manage that process for me?

It just so happens that Rebecca Collins from Hobeck Books, she and I are friends, and she posted something on Facebook about some work that she was doing for another client that was exactly that work. I thought, oh, hang on a minute, I didn’t know Rebecca did that.

So I gave her a call, and we had a chat, and it turned out that she had availability, and she had exactly the skills I need. So it started with Rebecca, and then it slowly grew. So I’ve sort of added one person at a time, and over time people’s roles have grown, so there’s been more work for them to do.

Rebecca’s gone from doing one day a week to doing two days a week. I’ve got Catherine Matthews, who also works for SPS, she’s running my shop.

The great thing is she also runs Clare Lydon’s shop. She learns things when she’s doing each of our shops that she then uses in the other one, which works for both me and Clare. Clare and I are friends as well. She writes LesFic, and I think I recommended Catherine to Clare.

Having people on my team who have got experience and skills in areas that I don’t necessarily have, or who can dedicate a bit more time to learning about something specific.

So the Shopify store, Catherine and I were both quite new to that when we set it up. I said to her, well, I will pay for your time learning how to use Shopify and how to get my store set up. She went away and has been really good at just taking it on board and working things out for herself.

I could have done that, but it would have taken me a lot of time that would have detracted from the writing.

The other real challenge I’ve got is in my personal life, I have an autistic son. He’s not severely affected by his autism, but it does mean that I have to be available for him more than you might do for another teenager, and that can really throw things.

Having people that I can delegate things to, it’s incredibly helpful, because I know that my business isn’t going to just slide if my son needs me. It means that I’ve been able to focus on him and develop my author career at the same time. I’m not sure I would have been able to do both at this level.

Joanna: Yes, I love that. It’s so interesting, because you must be ambitious, because this is an ambitious move.

Rachel: Yes.

Joanna: Do you identify with ambition? Is that a word you identify with?

Rachel: I do.

Joanna: Yes, but you haven’t mentioned, oh, I want to be a seven figure or a multi-seven figure author.

Is money a motivation?

Rachel: Money is a motivation. That’s less about the cash, It’s more about a lifestyle. I have a lifestyle now that I really enjoy. So I spend a lot of time traveling. A lot of my books are based in Dorset, and I have a flat in Dorset now because I spend so much time down there.

It’s right on the beach, and it’s an absolutely wonderful place to go and clear my head, and get fresh air, and go for walks, and write, and take the family down as well. We spent a lot of time down there in the summer.

I’m working on a series, which is a spin off series for one of my characters, and each book will be set in a different European city.

Joanna: Oh, I wonder why?!

Rachel: Oh, let’s travel to those European cities. I listen to you talking about your research trips, and I think, yes, I want a bit of that. I’m going to Dorset, and I’m going to Scotland, and I’m going to Cumbria for those series. It’s great, and they’re wonderful places to visit, but why not go to Paris?

Joanna: Then you’re going to have one set in like a Maldives scuba diving resort!

Rachel: Absolutely. I’ve got a series that I write with Millie Ravensworth, who’s actually two authors, Heide Goody and Iain Grant, that is set in London on a vintage route master London tour bus.

We’ve got two amateur sleuths who, because they’re running these tours, they find themselves in the middle of mysteries in iconic London landmarks. We were thinking, why don’t we get one of them to go and work as a guide on a cruise ship or something so we can do that? So there’s a bit of a debate going on about who gets to do that research trip if we do it.

Joanna: Yes, and I think this is important, too, because —

This is a lifestyle that we’re doing for creative reasons, but also to have input into our ideas.

Like, I never have any problem justifying this. I do want to come back to that I’m fascinated with the ambition to do this because you’ve already grown so much. You’re working with these co-writers, but essentially, what you’re building with Ackroyd Publishing is it’s a publishing imprint that does crime books.

It made me think of Bookouture. If American authors don’t know, Bookouture is an imprint. It started in crime, and it grew, and it got bought for a ton of money. I wondered—

Are you looking forward into the future and seeing that you might sell the business?

Or that you want to grow much bigger? Or do you have grand plans?

Rachel: I think I’ve toyed with the idea of growing and publishing other authors. So I do have a couple of authors who are Ackroyd Publishing publishers who are not crime authors. One is my wife, Sally Brooks, so that’s kind of cheating, but she writes lesbian rom coms and sapphic rom coms.

She has a day job. She loves the writing, but doesn’t want to do the marketing and business side of it. So I said to her, well, how about if Ackroyd Publishing published you? To be honest, it doesn’t mean we’re working together because it’s actually the team who are doing that. I’m not very heavily involved in the publication of her book.

I’ve also published Hazel Ward, who writes women’s fiction. She is somebody who I’ve known for years, and I’ve been a beta reader for her books since she started. So it’s very much been really, really slowly doing that. Only working with people who I know are really good writers and really good to work with.

I talked to Keshini at Hera, who published my paperbacks, about what it’s like managing a lot of authors. It’s hard work, and you’ve got to juggle a lot of different expectations and a lot of different styles of working in terms of what they expect from the publisher. I’m quite wary of that.

I’m more interested in building a group of co-authors who work with me, so that I am still the brand.

I’m building a really loyal readership. I’ve got thousands of people who will buy my books on the days they come out.

What I do, it’s more like the James Patterson model, in a way. So I’m working with a co-author. They write the first draft and I write the second draft. We plan it together.

So what I do in the second draft is I will add in character detail, because I have characters who move across series, and I will also add in location detail, because we tend to write about locations that I know about. Although the Cumbria Crime ones, Joel Hames is getting to know Cumbria better than I do.

I will also tweak the style so that it’s a style that my readers are familiar with. So that when a reader comes to a book that’s co-written by me and any one of my co-writers, they will be slightly different. They won’t just be exactly the same as a Rachel McLean book that I write on my own, but they will feel familiar.

They’ll have a similar sort of structure, in terms of the number of chapters, the length of chapters, the style of writing, what you can expect from that book, the level of gore that you get in a crime book, the level of humor.

Although that’s different for the cozy mysteries, they’re definitely funnier. That’s why I write with Heide and Iain is because they are comedy writers, and they’re really good at that.

It’s about building up that brand and bringing other people into it and involving them to help create more IP.

Also, they’re all people who I know and have worked with have known. I mean, Heide and Iain, they were the people who first got me into self-publishing, so it’s really nice to be able to involve them in it and work with them.

They both live fairly close to me, so we’ll do research. One of the series we’re writing is in Birmingham, so we’ll meet up, and we’ll go for a walk around the locations and find the place the body is going to be dumped and that sort of thing, and then go and have lunch and plan the book. So it makes it really enjoyable working. I’m working with friends.

The team in Ackroyd Publishing that I’ve built as well, we’re developing friendships within the team. It was great when I got everybody together last March and we went down to Dorset to see everybody getting on so well and enjoying themselves.

Obviously, that’s important if you’ve got a really small team. So I think it just adds another dimension. It takes a little bit away from that loneliness of being a writer sitting in your room producing words.

Joanna: It doesn’t sound like that’s your life at all.

I love that you mentioned James Patterson because he gets a lot of flak because he is the most read author, the richest author, the guy who sells the most books. As you say, he co-writes with lots and lots of different people, in lots and lots of different series.

He does still have his own, I think that Alex Cross series is just his. I think what’s also interesting is you have Ackroyd, or you mentioned before, “crime books that readers want to read.”

I just want to remind listeners if they don’t know, and I’ll link back to our first interview, but you were not successful with your first books, right?

Rachel: No.

Joanna: And you pivoted to write crime books that readers want to read. So can you maybe just go into that a bit more? As in—

How do you know what readers want to read?

How do you add in this kind of Rachel McLean secret sauce that makes your book sell so much after failing at the beginning?

Rachel: Well, I started out by writing books that crossed genres and found it really hard to market them in any of the genres that they were in. What was useful was that I learned a lot about marketing during that time.

So when I did pivot to crime, I already had a head start there because I already had a mailing list that I’d started to grow. I already knew how to advertise and so forth.

What I did, it was January 2020, and I was at a point in my day job—I was a technical writer, I wrote about WordPress—and WordPress was in the throes of changing the programming language that it used.

I was either going to have to go back and learn JavaScript, or I was going to have to double down on the publishing and make a success of that. I was definitely keener on making a success of my writing than I was on learning JavaScript.

I thought, right, what do I need to do in order to reach more readers?

I was inspired by people like JD Kirk, Barry Hutchison and LJ Ross, and looking at what they’d done and the kind of books that they’d written.

Something that was becoming very prominent at the time was, in crime, the idea of the location being a key element and almost being like another character.

So my first series, which I wrote in 2020, was set in Birmingham. Those were the Zoe Finch books. I wrote those in Birmingham because I knew Birmingham like the back of my hand.

It actually turned out quite convenient because it was lock down and I couldn’t have gone on research trips anywhere. I was using Google Maps the whole time. I was probably responsible for half the statistics on people using Google Maps that they do at the government briefings every evening.

What I did was I read authors of crime and thrillers who were very successful. So I read books by some of my comp authors who were published by the smaller digital-first publishers and the big indies. I read books by people like James Patterson and Dan Brown.

I pulled apart what it was about their books that worked and what readers liked. I also read their reviews.

I was inspired to do that by, I can’t remember the name of it, but I think it’s Six Figure Author by Chris Fox. He said, don’t read your reviews, read your competitors reviews, and find out what it is that readers love or hate.

Sometimes what readers hate will be exactly the same as what they love because you’ll get some readers who are turned off by the very thing that attracts other readers to the book. So I did that, and the thing that came out was the locations and the characters.

So I spent quite a lot of time identifying what my locations were going to be. Also a lot of time working on my characters and my central team, and I developed them. Then when the Zoe Finch series came to a close, I thought, right, where am I going to go next?

I’d been visiting Dorset since I was a child. I first went there as a baby. My parents had a caravan down there. So I know Dorset really, really well. So I thought, I’ll go down to Dorset.

It felt quite risky moving onto another series, because Zoe Finch books had sold enough for me to be able to give up my day job. They hadn’t been hugely successful, but I was a full time author, which was what I wanted to achieve. So I moved to Dorset, and it turned out to be the best thing I ever did because a lot more people want to read about Dorset than want to read about Birmingham.

Joanna: For Americans who might not know, it’s a lovely coastal area, as opposed to a gritty, massive city.

Rachel: Exactly. Imagine reading about Maine as against reading about Boston, I suppose. The other thing that worked really well was the character that I moved to Dorset, DCI Lesley Clarke, she was Zoe’s boss in the Zoe Finch books. So she was a DCI.

I always enjoy writing sidekicks. I sometimes find sidekicks are a bit more real in my mind because I can see them through the eyes of the protagonist. I loved writing Lesley, so I thought, I’m going to move this grumpy middle-aged Brummie down to Dorset and see how she copes and what they make of her.

People love Lesley. Some people hate her. I’ve sat in author events where people have had arguments over whether they like Lesley or not, but as far as I’m concerned, that means she’s real in their minds whether they like her or not. She is quite grumpy and she doesn’t suffer fools gladly.

So, yes, it turned out to be the best decision I ever could have made to write a series in Dorset. I thought I was bringing that series to a close nine books in because there was a series arc. That’s another thing I always do in my books, there is always a series arc.

That might be police corruption or the death of a major character, well, who would have been a major character. So it’s Lesley’s predecessor. That came to a close, and I thought, right, that’s it, I’m done with these books.

I constantly kept having people say, is Lesley coming back? When are you going to write Lesley again? I had about a year of that, so I’m now writing another nine books in that series.

The paperbacks will be published by Hera. So Hera have republished the Dorset Crime existing books in print, but they’ll be publishing them as new books in paperback. So that’ll be really interesting because I’ll be getting new books into bookshops.

Joanna: That’s a traditional publisher?

Rachel: Yes. So Hera, they are a small publisher, a bit like Bookouture. So Keshini Naidoo, she used to work for Bookouture. She was the woman who discovered Angela Marsons.

What I like about Hera is that they are all about mainstream fiction written by diverse authors. So their authors are not the normal run of the mill people you expect to be published by traditional publishers.

They were interested in my books because Lesley is gay, and I always have gay characters in my books. It’s working really well working with Hera. The way they work, and their ethos and their values fit really well with mine.

Because they’re small, I’m sure I get a lot more attention than I would if I was at a bigger publisher. We just work really well together.

Joanna: So I want to come onto something—

Amazon recently named you as one of the top 10 most read authors on Kindle Unlimited in the UK over the last 10 years.

[Press release here on Amazon]

That is astounding. Like, how did that feel, by the way?

Rachel: Oh, it felt amazing. It was really funny because the evening that it happened, JM Dalgliesh was number eight, and I was number nine. He posted a screenshot of it to Facebook where he cut it off under his name, and I thought, oh, I’m not on that list. Then Sally, my wife, she went and found the press release and said, “There you are on the list, you’re just underneath him!” So I joked about it with him afterwards.

That felt like a huge achievement because there’s some really big names there, and also there are people who’ve been writing a lot longer than me.

It’s only been three and a bit years that I’ve been publishing my crime books, and to have sold enough to be one of the most read authors in KU in that time, it felt great.

My readers were lovely about it, because obviously I put in my newsletter and my social media, and readers were so pleased for me.

One of the things I love about being an author is that your readers want you to succeed, and they want to help you.

I refer to my readers as my reader army. I do things like when I’ve got a new edition of a paperback coming out, or a new book coming out, and I want them to buy in bookshops, I’ll say to them, “Right, you’re my reader army. I want you to go into bookshops and ask them to stock it.”

They’ll do it. They want to help me out. So, yes, it was great.

Joanna: I wondered because you’re so big on KU, which is obviously eBook first, you mentioned Shopify earlier, and also now books in bookstores.

How are you getting your readers to move from reading just in KU, into buying from your store, buying from bookshops, buying in other ways than they’ve been used to?

Rachel: Yes, that is a process that we’re still working on and experimenting with. So Alex, who works on my advertising, he is experimenting with various ad campaigns that run to the store.

One of the main benefits of running ads to a store, as I know you’ve mentioned on your podcast, is the fact that you can use conversion ads instead of traffic ads in Facebook. So Facebook actually knows if they’re converting, and can therefore run better targeted ads.

It also means that we have access to data. So I know who’s buying books, and I can retarget them, and I can upsell and so forth.

Where I’ve had the most success is in audiobooks because I found that people seem to be less wedded to listen to an audiobook on Audible than they are to getting their eBooks on Amazon. People find it difficult to understand that you can read a book on your Kindle that you haven’t bought from Amazon.

So I’ve been pushing quite hard on audiobooks. I’ve been pushing the fact that I have a release date for my audiobooks on my website, which is the same as the release date for the eBook and the paperback.

It’s a reliable release date. If somebody pre-orders it from me, they will get their file on that date. Whereas Audible, I can’t set a release date, I can’t set a pre order. I found that starting with audiobooks has been quite successful.

I’ve been doing it mainly through my mailing list, through my newsletter, and slowly educating people and encouraging them.

My next experiment I’m running, right at the end of this month it starts. I’m running a kind of Kickstarter, but I’m running it on my website instead of on Kickstarter. So it will be a two week period. So I’ve already got a sign up page for people to be notified when it goes live, and it’ll be a two week period.

I’ve produced a coffee table book, which is Rachel McLean’s Dorset Crime Trail. It’s the story of each of the locations from each of the books in the series and why I chose to write there. It gives you information about the location, but it’s told through the lens of me doing research trips to those locations. It’s very anecdotal. There are stories from my childhood in those locations and that kind of thing. Lots of photos, including stock imagery, but also my photos as well.

So that’s going to be exclusive to my website for two weeks, and there’s going to be bundles and so forth, and add ons, just like you would with Kickstarter.

I figured that it was probably easier, because I’m already trying to educate my readers to use my website, to continue doing that than to add another platform in right now. Crime readers tend to be older and tend to be less likely to be on Kickstarter.

I got the idea for doing this from Elana Johnson, who has done the same thing. She writes cozy—well, not cozy—sweet romance, and so the demographic of her readers is quite similar to mine. She has run “Kickstarters” on her website very successfully, so we’ll see how it goes.

I mean, obviously it’s the first one, and there’ll be teething problems and so forth. It’s turning out to be a lot more work than a normal launch. I was on a video call to Rebecca, my publishing manager, yesterday, and we were trying to work out all the dates.

So it was like, right, when does it go live? When do we have to place the orders? When do we send them out? When will they eventually be released? Bookshops want them as well, but I don’t want bookshops getting them until after the Kickstarter.

Joanna: Which is not a Kickstarter.

Rachel: Which is not a Kickstarter. A Kickstarter, non-Kickstarter, yes.

Joanna: I think what you’re talking about is essentially a bigger pre-order, and I think that’s really important to note.

Kickstarter is a brand. It’s a different website. It’s a very different model.

What you’re talking about, and what I think I’m going to do for a book as well next year, is that sort of pre-launch on your website for premium editions that you print after the pre-orders happen. Whereas indies are normally used to you can do a pre-order with an eBook, and it’s done, and it just goes out, and not a big deal.

I think that’s great, and I’m super jealous because I totally want to do a book like that around locations, but I have so many.

Rachel: Oh, and I know the problems that you’ve been having with your photographs of churches.

Joanna: Yes, photo permissions. Oh my goodness. Someone’s just said to me that you just hire someone and they do all of that. It just takes a lot longer than I’m used to, but I think that’s really interesting. On the audiobook—

You are selling the audiobooks through Shopify, so you’re directing everyone to BookFunnel?

Rachel: Well, as soon as somebody makes the purchase in Shopify, BookFunnel then sends them the email with the file.

Joanna: Just so people know, this is another app that people have to have. They have to have the BookFunnel app to listen to the audio. It’s fascinating to me that what you’re saying is people are more, I guess, happy to download a new app for audio than they are to consider using BookFunnel to get an eBook onto their Kindle device, which, again, is not difficult at all.

I think the more people like you and me and everyone, the more people who are actually educating people on buying direct, the easier it’s going to be. We have to remember, this is only year one or two of the kind of move into selling direct.

Fast forward five years, 10 years, where will we be then? I think it’ll be a very interesting ecosystem of what we can do with these direct things. I love that you’re doing so much.

So on that, I do want to ask you as well, authors love to use tools. Now, you’re working with a lot of freelancers. You’re working with different publishers. You use different tools. One of the big discussions right now for authors is AI. So I wondered—

What AI tools are you using as part of your business?

Rachel: I use ChatGPT to help with when I’m coming up with ideas for books and when I’m brainstorming. So the first book in my Petra McBride series, the one that’s set in Paris, I had an idea which was around artworks in the Louvre.

So I needed to find artworks with particular themes, and I needed to expand on those themes and think about how those might relate to characters. So I spent a day just on my phone with Chat, just throwing ideas back and forth, and getting it to identify artworks in the Louvre that might fit with this idea.

Then getting it to tell me about areas of Paris that exemplified the kind of people who fit with the themes of these artworks. Then once I’d done that, I sort of shortlisted and came up with a final list of the artworks that I want to use in the book.

So what I then got ChatGPT to do was give me a walking route around the Louvre which will take me to all of those artworks in the most efficient way possible. So that when I go there on my research trip, I don’t have to wander around the Louvre for hours trying to find all these places.

Also, I wanted it to find artworks that would be near the Mona Lisa, for example, but that’s not the Mona Lisa. So nobody’s looking at this other artwork, and that kind of thing. I got it to identify what they were near and what else would be going on in that part of the building.

So it’s really useful for that kind of thing, so I use it at that point. Also, when I’ve got a whole load of ideas for a book and I’m trying to pull them all together into a coherent structure, I’ll put what I’ve got into ChatGPT and get it to help me shuffle all the parts together and put them into a coherent structure.

I do a lot of the start of my location research often on ChatGPT. So I’m currently writing a book set on the Isle of Arran in Scotland. Before I went there, I spent a lot of time on ChatGPT. It’s based around archeology, this book, researching archeological sites, the history of the island and so forth.

Then getting it to give me sources because sometimes it does make things up. You have to be aware of that. So getting it to give me links and sources, and then delving into those, and then finding places I could visit.

I also use Novelcrafter. So I use Novelcrafter with Chat and with Claude to help me with editing. I’ll put a first draft through a pass of a fine tune that I’ve created in Novelcrafter before I then do the second draft. So it cleans it up for me.

I’ve developed a fine tune that is based on my own writing, where I fed that into ChatGPT. I’ll put my first draft in and get it to run that fine tune, so it just tidies up all the messy bits before I do the second draft.

I find also ChatGPT really helpful because I do a lot of dictation.

I’ll often dictate a first draft, or I dictate my newsletter quite a lot. So I’ll do my newsletter when I’m sitting in my car waiting to pick my son up from college or something, and I dictate it.

I use Otter.ai to dictate because I find that Otter is really good for the accuracy of picking up the right words, but it doesn’t add punctuation. It doesn’t add speech or anything. It adds punctuation as if you’re in a meeting, and assumes that you’re different speakers, instead of adding dialogue.

ChatGPT, when you give it something in Otter, it’s really good at working out what’s actually going on in terms of what’s dialogue and what’s not, and adding the paragraph breaks in the right place, and punctuation. So I do that as well, and that speeds things up, both with fiction and with the newsletter.

I’m constantly looking for new ways to use it and for it to help me be more efficient and have access to more information.

Joanna: I love that. I do think those of us, like you and I, we’re pretty heavy on our research, and we use places. Like you say, if you use places and art, I also have a lot of art history in my books, and archeology and all of that. It does just really help to have a creative collaborator to help you.

I often will do exactly the same as you. I was thinking listening to you, and this is the point with AI to me as well, you are leveraging a tool to make more Rachel. Like Rachel more Rachel, for you to put more stuff out into the world.

You’re also working with other humans who are helping you put more Rachel out into the world. I’ve also been wondering about how many issues people have with AI. I wonder, partly, if it’s to do with creative confidence.

You are a confident writer. You’ve written millions of words at this point, as have I. Your tone of voice, my tone of voice around AI, it has no emotion. Or the only emotion it has is happy and positive. Like this is a great tool, this is really helpful to me, and I can do more with this.

I guess how I’m thinking about this is we’re confident that what we produce is our work. Also, you came out of technical writing, and I was an IT consultant.

Do you think our technical experience plays into confidence around AI?

Rachel: I think so. I think the fact that I worked in IT before means that my default position with any new tech is to want to explore it and see what it can do for me, rather than to be scared of it.

I also believe very strongly that AI in itself is not good or bad. It is just a tool, and if good or bad things are done with it, that is because of the people who are doing those things. So if people use AI unethically, that’s not the fault of the AI. That’s the fault of the way that those people are either using or configuring the AI.

You talk a lot about doubling down on being human. Obviously, I’m using AI so it’s not the full extent of my creative process, by any means. I’m adding on. I would never release something that had just been written by AI. I always work on it as well.

I also don’t release books that have just been worked on by one of my co-authors. I work on them as well because I’m adding that Rachel. I mean, I actually call it Rachelifying.

Also, I’ve been doing a lot more video.

So it’s that thing of being visibly human and being yourself. So, interestingly, I’ve been using TikTok, but I hardly ever put videos out on TikTok, but I use TikTok as a video editor. TikTok’s editing tools are really good, and you don’t have to pay for them.

If you download the video that you’ve created before you publish it, you can download it without any TikTok watermarks on it, and then I’ll use it on Instagram or my newsletter or whatever. So I’ve been doing quite a lot of video, like little snippets of me.

A thing that’s becoming quite a part of my brand is me walking along a beach somewhere, talking about what the weather’s doing, and where I’m going today to research the next book. Also, where I’m going to dump a body.

If you ask my readers, what does Rachel do? It would be she finds a beauty spot, and she dumps a body in it.

I always do videos from my crime scenes, and those go out on social media on publication day.

It’s me, standing in the crime scene, telling people, “Right, this is where this is going to happen. This is where the tents are going to go.” Forensics and all that sort of stuff. It just brings it to life for readers, and I think makes them feel part of that world that I’m creating as well.

Joanna: I love that. I keep thinking, yes, I must do more video, and then I just never do. I was looking at some of yours because they’re on your Shopify store as well on your book pages, and I really think that is great.

I mean, it kept me on your Shopify store page to watch a video, which gives all the signals to the algorithms or whatever. So I think, actually, it’s a really strong thing to do that. So I urge people to go and have a look at one of your videos.

As much as I think you’re amazing, I mean, it’s not like they’re amazing professional videos. They’re pretty human.

Rachel: That’s part of the brand is. So, for example, I recently bought a gimbal, which is a stick thing that you put your phone on and video yourself, and it supposedly self-levels and follows you as you move around. Sometimes it goes wrong, and sometimes I don’t put my phone in it properly, and the balance goes off, and it just goes a bit weird.

Instead of thinking, oh, I need to edit that out, I’ll just laugh about it and say, “Oh, it’s doing it again. I’ve got to work out this gimbal,” and that just becomes part of what readers enjoy, that you’re not trying to create this really polished thing.

I do a lot of video where I’m somewhere where it’s windy, and I’m yelling to try and be heard. I have got little lavalier mics with the little fluffy thing on to stop the wind noise. I’m sure there’s a technical term for it.

Joanna: It’s called the dead cat.

Rachel: The dead cat, that’s it. Oh goodness.

Even so, when you’re standing on top of a mountain in Scotland filming a video of a crime scene, there’s going to be wind noise, and I’m sort of yelling into the camera.

Sometimes I’ll end up just doing a voiceover afterwards, but people quite enjoy that. They find it quite funny that I’m about to get blown into the sea somewhere or something like that. So, yes, I think that lack of professionalism.

I would say to people, if you’re planning on making video, don’t worry at all about it being polished. Just record yourself in a natural way, as if you would if you were sending a video update to one of your friends or family or something like that. Just make it you.

Joanna: Well, I’m excited to talk to you again in like two and a half years. So it’s been two and a half years since we last spoke, and in two and a half years, it’ll be very interesting to see where you are then because your trajectory is looking pretty good.

Tell people where they can find you, and your books, and everything you do online.

Rachel: Yes, they can find everything at RachelMclean.com, which is where those videos are. All my books are available for sale there as well, and my newsletter.

Joanna: Brilliant. Thanks so much for your time, Rachel. That was great.

Rachel: Thank you.

Takeaways

- Rachel MacLean has sold over two million copies of her books.

- She has scaled her business by hiring a team of freelancers.

- Engaging with readers is a top priority for Rachel.

- Collaboration with co-authors enhances creativity and productivity.

- Rachel enjoys the flexibility of managing her own team.

- Ambition drives Rachel, but lifestyle is also a key motivation.

- Understanding reader preferences is crucial for success.

- Location plays a significant role in her crime fiction.

- DCI Leslie Clark is a beloved character among readers.

- Rachel plans to expand Ackroyd Publishing with more authors. Hera focuses on mainstream fiction by diverse authors.

- Being recognized as a top author is a significant achievement.

- Reader engagement is crucial for an author’s success.

- Transitioning readers from ebooks to physical books is a process.

- Audiobooks have been a successful avenue for reaching readers.

- Innovative marketing strategies can enhance reader engagement.

- AI tools can assist in brainstorming and structuring ideas.

- Authenticity in branding helps connect with readers.

- Using technology creatively can enhance the writing process.

- Embracing new tools can lead to greater efficiency in writing.

The post Scaling An Author Business With Rachel McLean first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Today we’re going to be talking about a topic all writers have questions about at one point or another—and that is POV.

Today we’re going to be talking about a topic all writers have questions about at one point or another—and that is POV.

The Resolution is a bittersweet moment. You’ve reached the end of the story. You’ve climbed the mountain, and now you can plant your flag of completion at its peak! But as the finale of all your work, this is also the finale of all the fun you’ve experienced in your wonderful world of made-up people and places. The Resolution is where you must now say goodbye to your characters and give readers a chance to also say goodbye.

The Resolution is a bittersweet moment. You’ve reached the end of the story. You’ve climbed the mountain, and now you can plant your flag of completion at its peak! But as the finale of all your work, this is also the finale of all the fun you’ve experienced in your wonderful world of made-up people and places. The Resolution is where you must now say goodbye to your characters and give readers a chance to also say goodbye.

Creating the perfect ending boils down to one essential objective: leave readers satisfied. The Resolution begins directly after the Climax and continues until the last page. Resolutions can vary in length, but shorter is generally better. Your plot is over. You don’t want to test readers’ patience by wasting their time.

Creating the perfect ending boils down to one essential objective: leave readers satisfied. The Resolution begins directly after the Climax and continues until the last page. Resolutions can vary in length, but shorter is generally better. Your plot is over. You don’t want to test readers’ patience by wasting their time.

The Resolution takes place directly after the Climax and is the book’s last scene(s).

The Resolution takes place directly after the Climax and is the book’s last scene(s).

Recent Comments